A trip to a neighborhood lumber store in Pasig City reveals a growing array of wood available for new structures. Amidst the display of native narra, ipil, imported maple and oak, sit the delicate, light-colored bamboo floor planks.

The bamboo looks so different from those commonly seen in traditional native huts, furniture, scaffoldings, and lechon trays.

Technically a grass, the hardy bamboo’s versatility is bringing this quick-growing humble plant into the limelight.

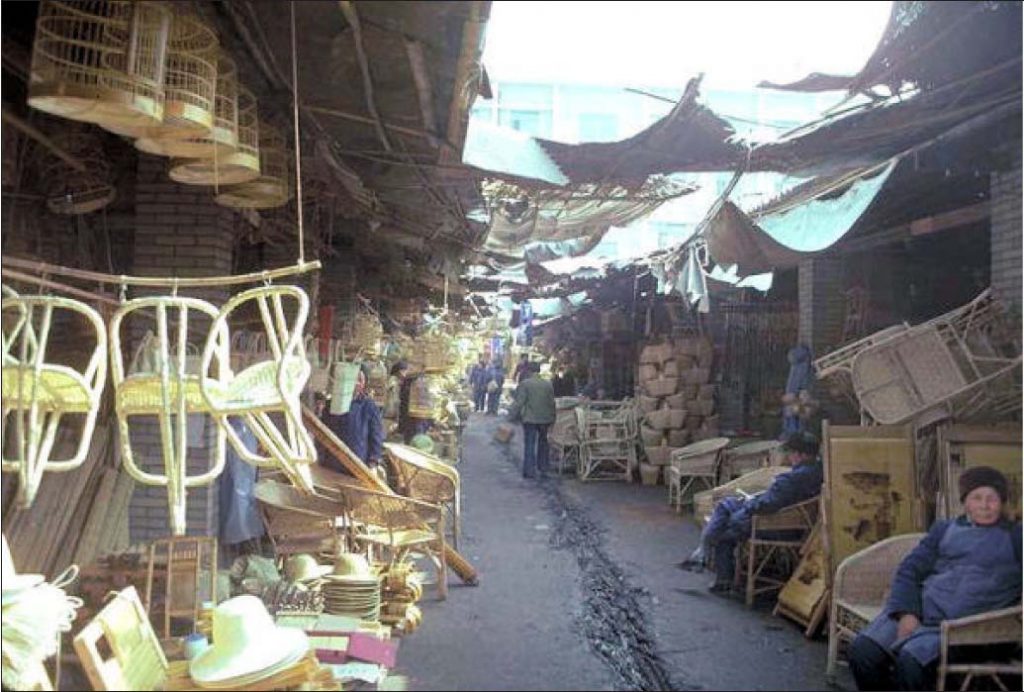

In a departure from traditional products like toothpicks, chopsticks, steaming baskets, birdcages and lacquered trays, growers in China today use it to make building material and fabric, revitalize forests, and rejuvenate rural economies, says a report in China Daily by Erik Nilsson in Anji country, Zhejiang province.

China produces about 80 percent of the world’s bamboo.

“Chinese culture is bamboo culture,” says Xuan Taotao, a government expert in Anji.

“Bamboo can make farmers rich and our environment healthy, so we must preserve bamboo forests and industries.

“It requires virtually no care and is harvested every two or six years. The farmers don’t have to work hard.”

With its versality, short growing cycle, and ability to grow on mountainsides, bamboo is being hailed by many as the “next super-material” and “timber of the 21st century.”

At last count, there are more than 1,500 uses for bamboo. Its versatility makes it possible to use the wood into a growing range of products that include home and office furniture, car speakers, calculators, buildings and beer.

An emerging product is bamboo textile. Producers of bamboo fabric say it is almost soft as silk, breathes better than other material, and more absorbent than cotton.

The World Bamboo Organization estimates the bamboo industry is worth about US$10 billion (P435 billion) a year. This can double by 2018.

Anji producers about 20 percent of China’s bamboo products, generating about RMB12.5 billion (P88 billion) revenue yearly.

Yet, it has only 66,667 hectares of bamboo, less than two percent of the country’s bamboo forests. It has been raising the plant for 60 years, and traded bamboo for rice with Shanghai, where the timber was used to build homes.

About 50 species produce more than 3,000 products in Anji. There are more than 3,000 bamboo-processing factories in the county of 250,000 residents. Until recently, the activity supported 90 percent of the local gross domestic product.

At present, as locals migrate to other cities, it is about 30 percent.

One local enterprenuer, Hu Gongnian, became wealthy from working with bamboo. He never went to school. Yet, it was his firm that produced the pillars for the German pavilion at the World Exposition 2010 in Shanghai.

Apprenticed to a bamboo carpenter at 17, he became a middleman at 20, and began making chopsticks and toothpicks in 1995. He began to produce flooring in 2005, then moved into furniture in 2007.

Today, his company Anji Cheng Feng Bamboo Products Co. Ltd. earns about RMB20 million (P142 million) a year, has 70 workers, and its factories cover about 1.33 hectares.

Tourism is also growing in Anji. Each year, more than 500,000 visitors hike the forests, eat bamboo dishes in local restaurants, and buy bamboo handicrafts. They want to see the filming sites of such blockbuster movies as “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.”

There is even a small museum dedicated to films shot in Anji’s bamboo forests.

Anji’s bamboo tourism generates RMB500 million (P3.545 billion) in annual revenues. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 26, no. 3 (July 9-22, 2013): 9.