First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 25, no. 3 (July 10-23, 2012): 8-10.

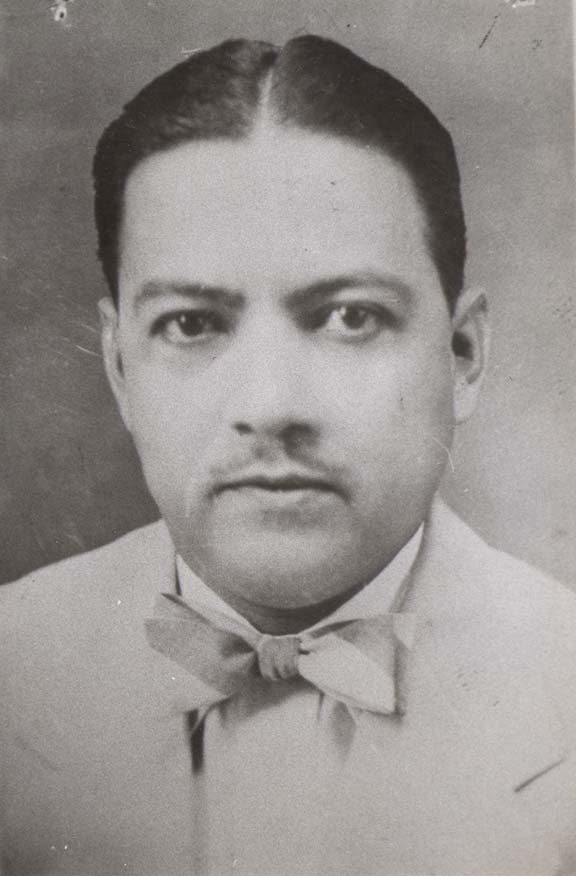

Quintin Paredes is more than a street name in Binondo. This name, which replaced that of Rosario, belonged to a lawyer, statesman and senator who had a prominent hand shaping Philippine history.

Quintin Paredes was born on Sept. 8, 1884 in Bangued, Abra to Juan Felix Paredes and Regina Babila. His father ran a school, Colegio de la Purisima Concepcion, where he studied as a young boy. His mother was daughter of an Itneg tribal leader.

Paredes was in his teens when the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) broke out. The first Americans to reach Bangued were 19 prisoners of the revolutionary unit under a Col. Leviste of Abra. They were lodged among the town’s elite. A major and a chaplain stayed with the family.

The elder Paredes treated them as befitted their rank and status, not as prisoners. Thankful for his hospitality, the men offered to teach his children English, which they accepted.

The young Paredes and his elder brother Marin proved to be the most adept pupils. Two months later when Americans officially installed themselves as the new colonial administrators, two American soldiers went to the house and took the two boys to camp. They went despite fears of imprisonment or worse. On arrival, the camp commander – a major – greeted them with a pistol aimed at them. It turned out the major needed interpreters.

Years later when a grown-up Paredes visited the United States, he met the major, by then a retired general. In front of dinner guests, the general showed how he used to hold Quintin as a young lad: on his lap!

In those early postwar years, knowing English helped Paredes get work as court interpreter and stenographer to earn the money he needed for a good education. He first enrolled at the Colegio Semenario de Vigan (now the Divine Word College of Vigan) and then at Manila’s San Juan de Letran. After graduation, he worked as Abra’s assistant provincial treasurer in 1902 before resigning to study law.

Most accounts of his life said Paredes enrolled at the Escuela de Leyes, literally “Law School.” Research fails to show the school’s existence today. Sources explained the law school was started by his brother Isidro, a judge and member of the Malolos Congress.

It is speculated that either law school tuition was unaffordable, thus his brother tutored him personally; or Paredes felt no teachers in Philippine law schools at the time could match his brother’s legal prowess, and thus chose to be mentored by Isidro instead.

In 1906, Paredes was one of four who passed the bar exam. There were 70 candidates. While reviewing for the exams he met, and was smitten by 19-year-old Spanish mestiza Victoria Peralta, a widow and single mom. The two soon married. When it was time for Paredes to take the oath, Victoria sold a pair of her earrings so he could buy shoes for the ceremony.

After a few years in private law practice, Paredes was hired as Manila’s Deputy Fiscal in 1908, despite being the son of a provincial schoolmaster, without political connection and not having graduated from a prestigious university.

It was also during this time – 1909-1917 – that he taught criminal law at the Escuela de Derecho (Manila Law College today) and eventually served as its director.

At this time, Paredes was on the legal fast track. In 1916, after eight years as deputy fiscal, he moved into the city fiscal’s office. While there he promoted individual efficiency among public prosecutors by instituting a merit rating system based on accomplishment.

In 1917, he joined the Bureau of Justice where he distinguished himself in a case involving an American showman. The American wanted to hire non-Christian Filipinos for a traveling exhibit across the US. Paredes felt it would give the American public the impression the country was uncivilized, and hinder the work of those fighting for the country’s independence in the US courts and legislature.

At the time, a law preventing such an act did not exist. So Paredes had the American’s departure delayed until the law was passed, making the planned exhibit illegal! He became attorney general in 1918.

In 1919, he was made technical assistant to Senate President Manuel L. Quezon, and joined the ‘Independence Mission’ to the US: Philippine legislators traveled to the U.S. to work out the terms of the country’s independence as promised in the Jones Law of 1916. While there, he worked in the US Supreme Court as a specialist in international affairs and was sent to the U.S. District Courts for China to defend US citizens with pending court cases in China.

In 1920, Paredes returned to the Philippines and became Secretary of Justice. But he resigned the following year to protest then-Governor General Leonard Wood’s choice of an appointee to the judiciary, whom Paredes thought unqualified for the post. Following his lead, other cabinet members also walked off, leading to the Cabinet Crisis of 1923.

Paredes returned to private law practice and, with two others, formed a partnership that became known as Paredes-Buencamino-Yulo. Although regarded as one of the ablest lawyers of his time, he was eager to return to government. He was elected Abra representative to legislature in 1925, and went on to serve four more terms. In 1931 he was elected Speaker of the House, and in 1934, Speaker Pro Tempore.

His most enduring accomplishment as assemblyman was helping to decide whether to adopt American jury system. He opposed it because he felt that in the Philippines, a jury could be easily swayed.

“I do not think it will work out successfully in our country. The system requires every man and woman to take part in the administration of justice. I am afraid that our people are not yet prepared to share the intricacies of legal technicalities, so that instead of justice, there might be a travesty of justice,” he stated.

He favored trial by collegiate courts or one where a judge decided the outcome of a case. “There is no doubt that a defendant can find better protection of his rights from a collegiate court than from an individual one. The concurrence of plural minds on matters of fact and of law is the best safeguard of the people’s rights and liberties and makes for more deliberate and stable judgment.”

Paredes took his job seriously. At one time there was a lack of quorum in the House for an important vote. As speaker, Paredes had the sergeant-at-arms bring absentee legislators in to vote.

In 1935, he was elected to the National Assembly of the Commonwealth government.

Values and principles led him to oppose then-President Quezon’s push for Congress to pass quickly bills he advocated. Paredes thought rushing to approve laws was bad practice. As well, he believed legislature should be equal, not subordinate, to the executive branch of government.

Possibly to save face and prevent a political impasse, Quezon made Paredes Resident Commissioner to the U.S. in 1935, he was to represent Philippine interests in the U.S. Congress. He would have similar speaking privilege as an American congressman but without voting rights.

In 1938, he returned and was re-elected to the Philippine Assembly. He became majority floor leader. He further boosted his political profile by sympathizing with the Jews who faced Nazi persecution in Europe that began November 1938. He favored allowing Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria to migrate to the Philippines when other nations had closed their doors to them.

According to historian Manuel Quezon III, “The country was prepared to accept 10,000 Jews a year for a certain number of years… with World War II about to break out in Europe, only 1,200 Jews made it to Manila.”

When the Japanese took over the country in 1942, Paredes reluctantly headed up the Department of Public Works and Communications. To ensure he complied with Japanese government orders, one of his sons was taken to Japan.

Later as American liberators were returning to the Philippines, the Japanese took President Jose P. Laurel and his cabinet to Baguio and then Tokyo to evade capture. Paredes somehow made his way to the American forces and surrendered. Yet, he was still charged with collaboration and treason.

While awaiting trial, he defended Laurel from similar charges, alongside statesman Claro M. Recto. The charges were dropped when President Manuel A. Roxas proclaimed a general amnesty.

The war also brought tragedy to the Paredes family. Isidro, his eldest son was a pilot in the British Royal Air Force. He died when his plane was shot down over France by the Luftwaffe (German air force). It was only after the war that the father could go to France to reclaim his body and rebury him in the Philippines.

A year after receiving amnesty, Paredes won a seat in the Philippine Senate. Reelected in 1955, he became Senate President (though he only served the position for a month). He later became Minority Floor Leader.

As legislator, he was instrumental in revising the Spanish Penal Code, and worked on the New Civil Code and the Magna Carta of Labor. He also advocated the creation of an information agency to disseminate news and stories about the Philippines to the rest of the world.

In 1961 he returned to private law practice.

When Paredes finally retired from public service, he did so with a clean record. According to granddaughter, Merle Basco, he would never accepted bribes because he was a proud man.

“If a person accepted any bribes, he would have found himself trying to please the person who offered the bribe. If you were a proud man like my grandfather, you would not have wanted that. You would have wanted to maintain your independence,” she said.

In later years, he received the Order of Sikatuna by President Ferdinand E. Marcos and was awarded as honoris causa (Doctor of Law) by the University of the Philippines. He also served as president for General Bank and Trust Co.

While other men look forward to more time with wife and family in their golden years, that was not so for Paredes. His marriage with Victoria, which yielded 10 children, eventually failed. When his children planned a golden wedding anniversary for them, Paredes refused to walk down the aisle, saying he and Victoria were no longer together as a couple.

After Victoria passed away, Paredes married Gregoria Yujuico, a pioneer in interior decorating. Yet, on Jan. 30, 1973, as he was dying, it was Victoria’s name he uttered on his deathbed. He was buried at Manila’s North Cemetery.