Bamboo has been hailed as the new super material, with over 1,500 uses identified so far. The global bamboo industry is estimated to be worth about US10 billion a year.

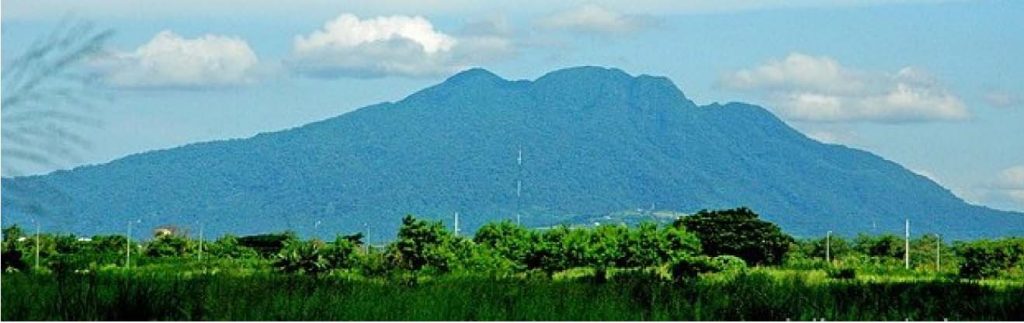

“With Mount Makiling standing guard with its majestic hue and Laguna’s placid waters lending splendor to the view . . .”

That is from a poem which became the lyrics of the “College Hymn” of the University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Agriculture. It was written by Dean Leopoldo B. Uichanco describing the beauty and splendor of Mt. Makiling where the town of Los Baños nests at its foothills.

The mountain with its verdant forest must have been a majestic view with the abundant flora. Among them are the bamboo species whose local names are reflected in names of barangays and even this very mountain.

Mount Makiling is named after a bamboo species, Bambusa vulgaris, known as kiling in Tagalog, lunas or taywanak in Bisaya. In Tagalog, kiling means to bend or lean. “Ma” is a prefix meaning “many” and so the word “Makiling” is translated as plenty of kiling. This bamboo species thrives well in this creek-laden mountain and is one of the most dominant bamboo species in Laguna.

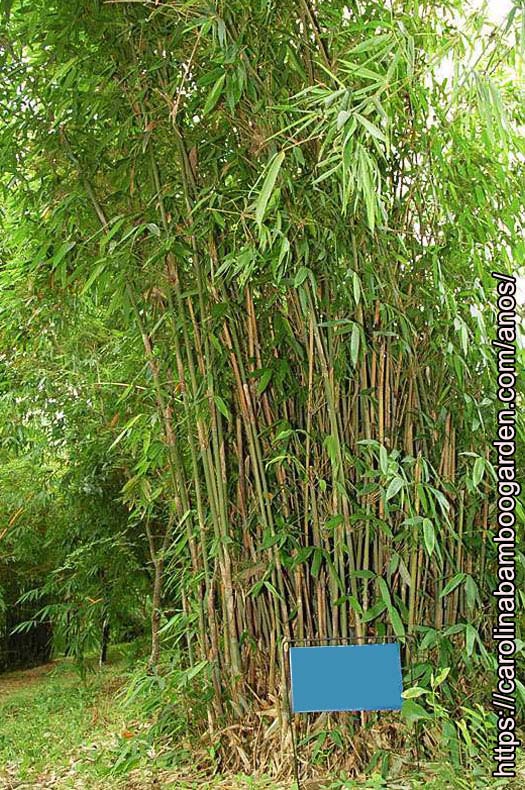

Anos and Bayog are two places in Los Baños named after bamboo. Barangay Anos goes straight from Bayan (Poblacion) to College, the area where the former U.P. College of Agriculture and now the UPLB is located; it is politically a part of Barangay Batong Malake. The bamboo Anos (Schizostachyum lima) is a medium-sized species especially used as fishing rods.

Barangay Bayog is at the lakeside of Laguna de Bay. The bamboo Bayog (Bambusa merrilliana or formerly Dendrocalamus merrillianus) is an endemic species found only in the Philippines. It is famous for its shoots as food and culms as furniture and construction material. These are only three of the many bamboo species now growing abundantly and being propagated in Los Baños.

The large scale commercial propagation of ornamental bamboo began in Los Baños.

Among the ornamental species, the Thailand or monastery bamboo (Thyrsostachys siamensis) became the king of ornamental bamboo in the Philippines and became popularly known as pole bamboo among plant nursery owners.

According to plant propagators in Los Baños (the Tamis brothers Gaudencio and Apolinario), they got the original plant from Bulacan Garden Corp. in the early 1990s.

Dean Dioscoro L. Umali brought this species from Thailand and planted them at his farm behind the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Research and Development.

Two known bamboo propagators (Rufina Umali Esturias and Emeteria Mercado) and landscaper Ponce Verdiano made history in the large scale propagation and production of this bamboo species.

Several people – including Ireneo Papa, Department of Environment and Natural Resources acting Secretary Ramon Ramon Paje, Juan V. Pancho and Ely Bardenas – were forerunners in advancing the importance of bamboo ornamentals.

Pole bamboo is planted almost anywhere in the Philippines and because of this, planting and selling bamboo ornamentals is now an important industry in the country.

Other famous ornamental species are the Taiwan bamboo (Bambusa dolichomerithalla), yellow buho (Schizostachyum brachycladum), Buddha’s belly bamboo (Bambusa tuldoides), wamin bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris cv. wamin) and the Australian bamboo (Gigantochloa kuring).

The creation of UPLB in this area paved the way for conservation of various bamboo species and varieties. The first bambusetum to be established was probably on the one at the Makiling Botanical Gardens which now celebrates its 50th year.

Other early bambuseta are those in the Hortorium of the UPLB Museum of Natural History and the Institute of Plant Breeding Bamboo Plantation.

With the establishment of different bambuseta of the then Forest Research Institute, now known as the Ecosystems Research Development Bureau of the DENR, the promotion of bamboo as an important non-timber forest product in the country was promoted.

The Los Baños Experimental Station of ERDB, located near the Makiling Rainforest Park, is the largest bambusetum in the country today, although it is supposed to be only a satellite of the Philippine Bambusetum in Loakan, Baguio City.

Other satellite bambuseta under DENR are in Impalutao, Malaybalay, Bukidnon where they have established clumps of the giant bamboo and in Nabunturan, Compostela Valley.

Maintaining bamboo collections in as many places in the country will be beneficial to the next generation of Filipinos.

They serve as living repositories of the species that are already present in a locality and a reference collection for other important uses in the future, such as biofuel and sources for ayurvedic medicine.

In the Philippines, there are at least 64 species of erect and climbing bamboo. Only around five are endemic; the rest are introduced. There might still be a few other species in remote forests and islands that remain unknown to science.

Additional species are some ornamental species brought over from China in the mid-2000.

Bamboo’s importance is gaining attention from all sectors of society. With its many uses, it is likely to be the most important non-timber woody product in the world especially in tropical countries.

Easily available in many of the world’s poorest countries, bamboo can be used to build low-cost, climate-resistant, sustainable housing. The bamboo’s strength and flexibility make it one of the best materials to withstand floods, storms and earthquakes. We could learn from our forefathers and revisit our very own bahay kubo.

Bamboo are being replanted along riverbanks to guard against further damage from flash floods.

They are among the only few species of plants that survive and continue to produce shoots during periods of intense rain and floods, characterized as La Niña.

All of these are just among the many reasons why we choose to work on bamboo.

In Davao del Norte, we grew up planting the laak bamboo that our family propagated to be cut and sold as propping for bananas in plantations.

As my late Dad, formerly known as the Bamboo King of Davao said, quoting another Asian author, bamboo will be the “savior of our ailing land.”

Far from Davao and now here in Los Baños, I still work on bamboo – germplasm collection, propagation, conservation – while my husband and I cooperate on insects that eat or just nest and live among bamboo.

By the way, we have nicknamed our youngest son Bamboo, long before we knew that he had a popular singer as namesake. Bamboo spells life and it has become a lifetime activity and advocacy. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 26, no. 3 (July 9-22, 2013): 8-9.