Having lived in Binondo all my life, I have seen Jones Bridge go through many changes. But I have never seen the bridge as popular as it is now, thanks to the renovation work commissioned by Mayor Francisco “Isko” Moreno.

In the past, people were usually busy just getting across, but now they stop, take pictures and admire the bridge itself. The bridge has become a destination for photoshoots and selfies, cars would stop in the middle of the bridge, with occupants out taking pictures. But for me, to properly appreciate the bridge, you have to learn about its history and current message.

When there were no bridges before, people traveled by ferry to cross the Pasig River. But because the ferrymen charged very high rates, the Chinese merchants of Manila took matters into their own hands and donated money to the government to build a bridge.

Construction began in 1626 and the bridge took four years to complete. When it opened, the bridge was called the Puente Grande. It suffered serious damage during the earthquake of 1863 and had to be closed. It was only reopened to traffic in 1875 and renamed the Puente España.

The Puente España survived well into the arrival of the Americans in the 1900s. But a typhoon severely damaged the bridge in 1914, and it was so severe that a decision was made for a new bridge to be built one block down the river. So, while work on the new bridge was ongoing, a temporary truss bridge was built on the ruins of the Puente España to enable traffic to pass through.

Around the period when the new bridge was being constructed, the Philippine Legislature was struggling to gain the country’s independence. Every year, since the governing body was founded in 1907, they would pass a resolution for the country’s independence. Then, in 1912, American Rep. William Atkins Jones drafted a bill known as the Jones Law. It was the first and formal declaration of the US government’s commitment to granting the country independence. The bill was later amended and passed in 1916, guaranteeing the country’s independence.

However, Jones died in 1918 and never got to witness the Philippines’ independence. The Philippine government then decided to dedicate the new bridge to him as a memorial. The government hired Filipino architect Juan Arellano to design the new bridge. As a fitting memorial to Jones, he made it more ornate.

He was inspired by a bridge that he saw while visiting Paris, the Pont Alexandre III. Like the Pont, the piers on the sides of the bridge would feature statues of boys playing with dolphins. It would also have two plinths or columns at each end where two statues would be placed. Far from just merely decorations, the four statues would be allegorical, representing the values that were espoused in the Jones Law.

According to the Public Works Bulletin dated Jan. 21, 1921, the statues represented the ideals of democracy, justice, gratitude and progress. They were later on collectively named Las Madres.

Arellano commissioned a young German sculptor, Otto Fischer Credo, to make the statues. Credo previously studied at the Akademie der Kunts in Berlin and graduated at the Royal Academy of Arts in Paris. Other sources, however, credit Filipino sculptor Ramon Martinez as the sculptor behind the Las Madres.

But blogger Lou Gopal posted photos on his website provided by Credo’s descendants of the Las Madres in his studio. This does not mean, however, that Martinez was not involved in the project – he may have provided assistance or collaborated at some level, but his efforts are not properly credited. While we are aware of the names of each statue, the allegories or meanings to their names are unclear. After extensive inquiries, it appears that there were no explanations or accounts left behind by those involved in designing the bridge, which makes decoding their meanings open to public interpretation.

Among those who attempted to do this is writer, historian and architect Gerard Lico. In his 2008 book, Arkitecturang Filipino, he focused on the four statues in his essay, “Casting the Imperial Allegory.” In his book, Lico noted that while all four seated female figures have western features, they are wearing the traditional Filipina costume, the baro’t saya. Because of this, Lico claims that they are representative of the Philippines itself, which is why all four statues are known collectively as the Las Madres Filipinas.

As to why women were chosen to represent the Philippines, Lico claims that the designers of the bridge were probably inspired by the painting, “Mother Spain guiding the Philippines down the road of progress” by the artist, Juan Luna. In the painting, both Spain and the Philippines were represented symbolically by female figures. As for what each statue means specifically, Lico starts with the one representing gratitude, which portrays the Madre Filipina comforting a grieving man on her left side and a young child on her right side.

Lico then describes the details behind the seated Madre’s throne: an urn with a rooster on top and an eagle. In his interpretation, the urn represents death while the rooster represents resurrection, and the eagle represents American power or intervention. Taken as a whole, Lico claims that this La Madre aims to remind us to be thankful for America’s introduction of public health and sanitation to the country in the early days of their colonization.

However, Lico is not the only one attempting to identify the allegory behind Las Madres.

Late last year, history enthusiast Lorenzo Bukas posted his own interpretation of the Las Madres on his Facebook page. According to him, the reason it was called gratitude was that it was a reminder to the younger generation to be grateful for the sacrifices of the older generation. While this seems valid, Bukas failed to consider the statue’s other details. The statue representing gratitude was then placed on the Muelle de Magallanes side of Jones Bridge, which is known as Liwasang Bonifacio today.

The La Madre that was placed next to it represents democracy, a woman holding a torch that stands for truth and enlightenment. In front of her are two children holding a wreath that represents triumph. Bukas claims that this La Madre signifies the hope that the Filipino people will one day triumph through education.

Lico, unfortunately, was unable to provide an interpretation in his essay, the reason being, which we will discuss later, that the statue has been missing since the end of World War II.

There was also a lack of detailed archival photos or film footage of this particular La Madre when Lico was doing his research. On the Binondo side of the bridge are the Las Madres representing justice and progress, with the latter being on the Escolta side.

On one side of the mother is a fallen man with hammer, which symbolizes labor, while on the other side is a child holding an orb, which is said to represent power. The mother herself is holding a torch representing truth. According to Bukas, the message of this statue is that children have power over their future through the hard work of their elders to provide them their education. Lico, on the other hand, interprets this as the support one gets from parental figures in the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness.

Then there is justice. The Madre Filipina sits with two kneeling children on her side.

One of the children is holding a fasces, a bundle of wooden rods tied together that symbolizes a judge’s power and jurisdiction. The other child is holding a key symbolizing knowledge and a tablet of the Ten Commandments representing law and order. Both Lico and Bukas agree that this statue represents equality under the law.

Since the statues are open to public interpretation, let me express my own opinions on the last three statues. Considering the context of the era when the bridge was built, the Americans, through architecture, were trying to create lasting monuments to symbolize their colonial power.

In his essay, Lico notes that he found a representation of the eagle in all the three Las Madres statues, representing America or America’s benevolence. So, if I were to interpret the La Madre representing democracy, it could be said that thanks to America, the Philippine was able to learn the truth about the benefits of a democratic system of government. As for my interpretation of the La Madre representing progress, the fallen man with the hammer could represent the failures and suffering of Filipinos under Spanish rule. But under America, future generations had hope for the future. The La Madre representing justice could be said that due to the Americans, future generations of Filipinos can live under the equality of the law. Currently, the interpretation of Bukas seems to be more widely circulated on the internet, making it the more acceptable interpretation by both the public and Manila City Hall. In fact, his interpretation will grace the plinth or column of each of the four Las Madres. Construction on the bridge began in 1919 and it was inaugurated in 1921. It faithfully served the public until it was destroyed by Japanese soldiers during the Battle of Manila in 1945. Out of the four statues on each side of the bridge, three survived. The statue representing gratitude was repaired by the sculptor, Anastacio Caedo, and was displayed in Rizal Park. The statues representing justice and progress ended up on the front steps of the Court of Appeals in Ermita.

As for the bridge itself, it was so badly damaged that an entirely new bridge replaced it. But instead of a neoclassical arch bridge, it became a modern industrial girder bridge. During the country’s centennial celebration in 1998, the bridge was given a partial restoration. The work was commissioned by then first lady Amelita Ramos and was overseen by architect Conrad Onglao.

When Moreno was elected mayor of Manila in 2019, he decided to renovate the bridge, as part of his plans to restore Manila’s lost glory. He approached Jerry Acuzar, owner of heritage park and resort Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar, and inquired what can be done.

The first thing they did was to focus on the concrete railing. Portions were demolished and then replaced by the pedestals of the new lamp post. The balusters were then painted in a faux marble pattern with undertones of orange, yellow and gold. The rest of the railings were painted green, white with touches of gold, but were later modified to just white and gold. Taking inspiration from the first version of the bridge, Moreno and Acuzar decided to rebuild the plinths on each end, and the statues that survived the war would finally regain their positions on the bridge. A new statue representing democracy was made to replace the one destroyed during the war.

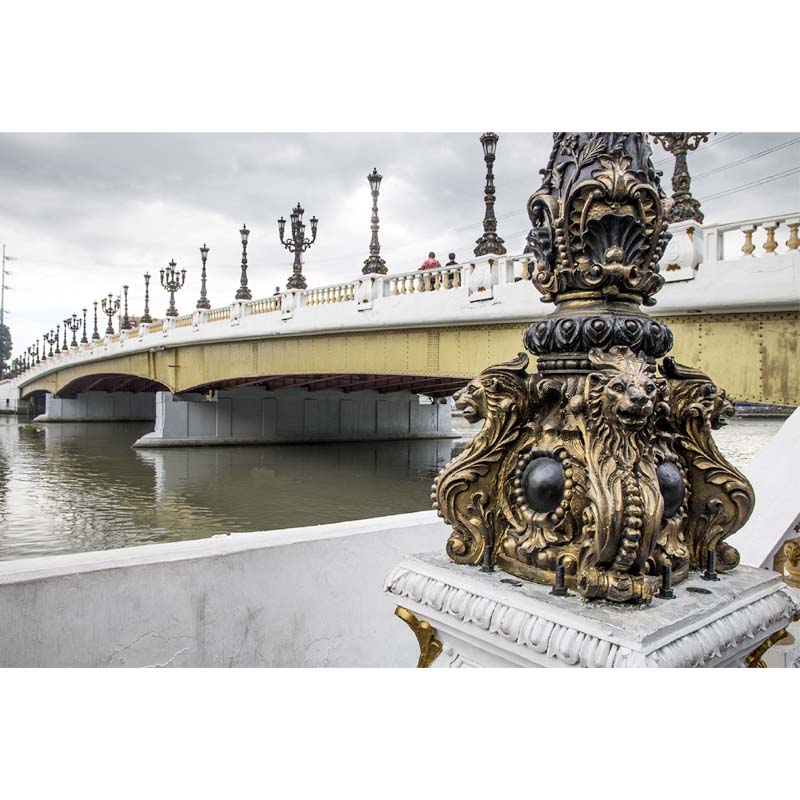

City Hall also replaced the street lamps installed by previous mayors with new Beaux art-inspired lamp posts produced by the workshop of Acuzar. Because of the salty air from Manila Bay and the Pasig River, it was decided that instead of metal posts, they would be cast from resin.

An interesting detail about these lamp posts is that their base features four lions or rather merlions, which is the official coat of arms of the City of Manila designated by King Philip II to represent the power of the Spanish Empire. It also appears on all the pedestals on the bridge.

Aside from the merlions, two granite Chinese lions stand guarding the bridge on the Liwasang Bonifacio side. The lions were donated by the Tong Tah Trading Enterprise of Singapore during the bridge’s 1998 renovation. These two lions will likely be incorporated in the current renovation of the bridge.

When the lamp posts were first installed, they were not bright enough to light the bridge at night, so additional lights were installed along the railings and under the girder of the bridge. New reflective road disks were also installed to clearly mark out traffic lanes. The lamp posts that were at the center of the bridge were then removed and replaced by a barrier covered with plants, and small outdoor speakers shaped like rocks were then placed among the plants, which would broadcast playlists of kundiman and old Filipino love songs to create an air of nostalgia.

The total cost for the bridge’s renovation is said to amount to P20 million, but media reports said City Hall did not spend a single centavo. The money was donated by the Philippine Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Inc. (菲律濱中國商會). If that is the case, then the PCCCII is following in the footsteps of another group of Chinese merchants four hundred years earlier.

At the moment, the bridge’s renovation seems to be one of Moreno’s pet project. From being a memorial to an American representative, the bridge is now seen as a testament of the new mayor’s vision and ability to get things done. But only time will tell if the changes instituted by Moreno on the bridge will be among his lasting legacy to the city of Manila.