The early dawn of March 31 found Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran members already up and on a bus traversing along Ortigas Avenue on the way to Rizal province for Kaisa’s annual summer outing. This year’s theme, “Kaisa goes Artsy,” aimed to explore the art and heritage scenes in the towns of Antipolo, Angono, Morong and Baras.

Most of us gathered at Bahay Tsinoy Museum for our bus ride. Some members brought along either their children, parents or siblings. This resulted in a fun family atmosphere inside the bus.

Once we settled in our seats, we were introduced to our guide, James Owen Saguisin, of the Angono-based tour company Viaje de Angono. He is more than qualified for the job. A former associate art professor from the Far Eastern University, he is also distantly related to National Artist Carlos ”Botong” Francisco.

After Bahay Tsinoy, we picked up some more Kaisa members along the way, near Wilson Street in Greenhills. Then we sped toward our first stop, Pinto Art Museum in Antipolo City.

The museum was started in 2010 by neurologist and former medical director of St. Luke’s Hospital, Dr. Joven Cuanang, and has become the place to view contemporary Philippine arts.

Pinto Art Museum is located inside a subdivision in Barangay San Roque. As we walked past the small-gated entrance, a 1.3-hectare space of beautifully landscaped gardens with white Greek Mediterranean-style villas greeted us.

The museum’s guide, Andy, cheerfully led us through the five galleries of the museum. Despite Andy’s sunny attitude and the museum’s beautiful surrounding, I found the subject of the artworks quite serious.

In the first gallery is a huge painting, entitled “Karnabal,” done by art collective Salingpusa. It pokes fun and satirizes the current Philippines by comparing it to a street carnival. In what appears to be a strip club, Filipina super heroine Darna is pole dancing.

In another gallery, an installation titled “Manufacturer’s Advice: Contents May Vary” by Alwin Reamillo features, among others, 44 tin cans, each with the face of the 44 members of the Philippine National Police Special Action Force killed in Maguindanao in 2015.

Of course, there were a few light-hearted works such as Kawayan De Guia’s untitled piece which features a horse made of torotot or horns. It was a clever piece as the horns were made of old movie film reels. From the foot of the horse, a bit of the film reel is seen sticking out. It was a funny piece and Andy demonstrated how, with one blow at a certain point, a toot will come out at the rear of the horse.

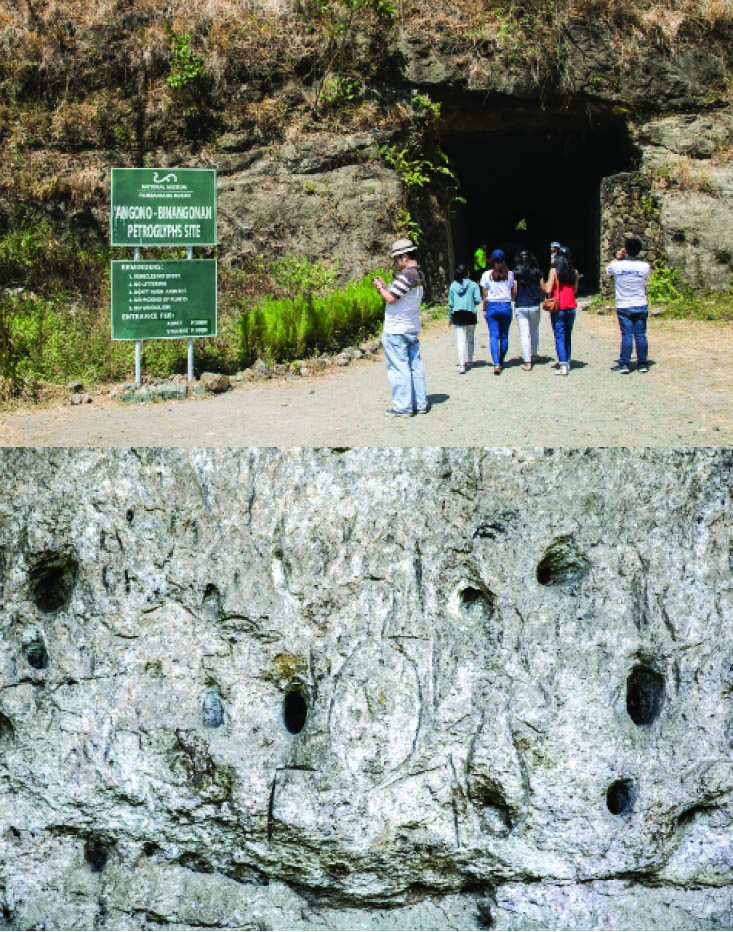

From contemporary Philippine art, we headed to the outskirts of Angono to view the 5,000-year-old petroglyphs or prehistoric rock etchings. These were discovered in 1965 by National Artist Botong Francisco when he was guiding a group of boy scouts in the area. The site is now looked after by a group that includes the National Museum and the Department of Tourism.

Upon arrival, we saw a tunnel ahead of us but it was not the site of the petroglyphs itself. It was constructed in the 1990s to make it easier for visitors to reach the site.

Our guide Owen gave us a brief background about the site and how we were to reach it. He instructed us to go through the tunnel and after another hundred meters or so, we reached the visitors’ center where we will be provided with a brief introduction behind the rock etchings.

The rock shelter itself where the carvings were etched is made of soft volcanic soils. Scientists claimed that they found at least 127 rock etchings depicting either a man, a frog or a lizard. But only 51 of these etchings were distinct enough to be seen with the naked eye as the rest have eroded or were destroyed over time.

After the orientation, we climbed up to the wooden viewing deck to see the etchings. Owen told us that the clue to understanding the meaning behind the etchings might be found in the two smaller caves.

He shared that the caves may have been a birthing chamber. The etching may be either the number of successful births or the spirits that look after the mother as she gives birth.

Another theory I found online was that the rock shelter may have once been a dambana. The sick person is placed inside the caves, while the figures were etched on the rock. It is believed that the illness of the person will be transferred to the etching.

Having just viewed the Pinto Art Museum, the contrast between the past and the present could not have been more obvious. But I did realize that these two places have two things in common. One was using art as an instrument of healing.

If the theory proves that the site of the Angono petroglyphs was indeed a place of healing, then Dr. Joven Cuanang is bringing the concept up to date with his Pinto Academy: Arts and Sciences for Healing and Wholeness.

While he is not promoting the idea of having your illness transfer to a painting or sculpture, he does believe that the way our brain reacts to creating and seeing art can become part of the healing process.

In an interview with The STAR, he pointed to a new branch of neuroscience called neuroesthetics. He believes that art has therapeutic applications such as the treatment of depression, boosting the immune system, pain relief and stress management.

The second commonality was how they were able to capture moments in our nation’s history. The Angono petroglyphs gave us a rare glimpse of the life of our cave dwelling ancestors 5,000 years ago, while Pinto reminds us of the social issues that we struggle with right now.

It would be interesting to see which of the art works at the Pinto Art Museum survives and perhaps a thousand years from now, how our descendants would interpret the times we lived in.

It was while we were viewing the etching that nature began making her presence felt at the rock shelter. A bright green snake crawled out from one of the holes above the rock shelter, making us gasp at its beauty. Owen then mentioned that aside from snakes, bats have been known to come out of the caves to eat the fruits that grow on the tree above the rock shelter. Owen pointed out a pile of seeds that the bats have left behind.

The maintenance of a beautiful outdoor heritage site, Meah Ang See mentioned to me, has its challenges. One such challenge is acid rain which could cause further erosion of the etchings. The National Museum, on its part, plans to cultivate more plants native to the area. This way, it will soak up more of the rainwater to prevent it from spilling into the rock shelter.

The theme of man and his environment continued on our next stop. Owen brought us to a site where a duhat tree used to grow. Owen explained that it would have been just another tree had not Botong Francisco frequented it to view the town of Angono.

The original is long gone and the area has since been redeveloped. But there is now a lookout tower in its place with a duhat tree growing in the middle of it. From here, we can see not only the town of Angono, but also the skyline of Makati and Laguna de Bay.

However, the breathtaking view is marred by a quarry not far from the town of Angono. The quarry has tried to cover up its operations by planting more trees next to the lookout tower, but it is not thick enough yet to hide what they are doing.

Since it was nearly noon when we reached the lookout point, our next stop was lunch at the Balaw Balaw Restaurant. The buffet menu served was typical Filipino fare of adobo, manggang hilaw at kamatis and rice.

But since the restaurant was also famous for its more exotic fare, we ended up trying out hantik (big ants), wood grub (uok) and alagaw leaves. The people of Angono learned to eat these food when times were hard and it grew to become part of the cuisine of the town.

But what fascinated me more than the food is that Balaw Balaw is more than just a restaurant: it is also an art gallery. Among the paintings displayed here are those done by a founder of the restaurant, Perdigon Vocalan.

There are also a lot of other works, including sculptures done by the artists of Angono today. If you find one you like, you can ask the price from one of the waiters.

While others lined up for the buffet, I climbed up to the third floor of the restaurant and found the workshop where they make the higantes or giant paper mache images. These are used during the town’s fiesta on Nov. 23.

Numerous websites claim that the practice was done as far back as the Spanish colonial period as a form of protest against the landowner. But Owen said they were only started after World War II by Botong Francisco. It was not meant to be any form of protest, but rather to add fun and color to the fiesta. They have since become symbols of the town.

After lunch, we walked off the calories by visiting two historic churches in Rizal, the San Geronimo in the town of Morong and the St. Joseph in the town of Baras. It turns out both churches have links with the Chinese. The San Geronimo Church was built in 1620 by Chinese builders to replace a wooden one built in 1586.

One can see the Chinese builders’ influence: beside the church was a Chinese fu lion. Owen explains that there used to be a couple, but the female lion was stolen in the dead of night. This is why this lion has his feet chained to the ground.

The St. Joseph Church was built much later in 1635. But four years later, it was burned down during the 1639 Chinese uprising, where more than 30,000 were killed. It was not rebuilt until 1682. For me, it was well worth the stop as both churches have something interesting.

In San Geronimo Church, there are paintings of the Stations of the Cross that appeared to have been painted in the 1700s. The Saint Joseph Church has an elegant interior. Another bonus was hearing the choir practice for the mass later that afternoon.

By mid-afternoon, we were rushing off to the final three stops. We were caught in bad traffic and had to make a restroom stop at the Balaw Balaw Restaurant.

We then headed for the Blanco Family Museum. It showcases the works of National Artist nominee Jose Blanco and his family.

It is very rare to find an entire family this involved and excellent in arts or in any endeavor. The family has managed to make a name by capturing every day scenes across the Philippines in hyper realistic detail. All the art works in the museum seem like they were done by one man and not an entire family.

Owen began the tour by explaining the symbol of the museum and the Blanco family: carp. It was originally a pun given by friends to their great grandfather, Juan, who was stout and bald.

A fisherman by profession, he was taking a break on a small boat with his tummy exposed. His fellow fishermen who saw him began laughing and commenting at how much he looked like a bunggan, a local fish that swims with its belly exposed.

Taking that monicker, Jose Blanco made the ordinary bunggan into a carp. By painting the carp with its belly up, it now looks like it is jumping out of the water. It now represents the colorful and active nature of his family.

Owen then led us down the museum’s gallery focusing first on the art of the children as they began dabbling in art. One particular piece highlighted by Owen features an old lady from the Mountain Province.

It was painted by Jan, one of Jose’s sons, when he was 12 years old. Three years later he painted the same subject, but only this time, one can see how much he grew in terms of skills. The difference was remarkable!

At this point we were joined by one of the sons of Jose Blanco, Michael. After the obligatory greetings and photo ops, we began asking how his father managed to raise a family of artists. To his father’s credit, Michael explained, he never pushed them into becoming artists.

While he did teach them how to paint and create works of art, he also encouraged them to take college degrees outside of arts, so that they will have a fallback in case their art career never takes off.

As we proceeded from gallery to gallery, we were astounded by the quality of the works. Michael admits they managed to avoid being envious of each other by acknowledging that each of them is good at painting certain types of scenes. For example, he admits his brother Noel is skilled at doing scenes involving water, which he finds difficult.

It was already dark when we left the Blanco Family Museum, but we could not leave until we had visited one last place: the house of National Artist for Visual Arts, Carlos ‘Botong’ Francisco.

I felt all throughout the tour that he was the invisible hand that was guiding us. From the choice of guides to the petroglyphs, to even being the mentor of Jose Blanco. In fact, the artists of Angono today would not be able to gain the recognition they have, had it not been for what Botong Francisco had achieved. It was only proper that we visit his house in Poblacion Itaas.

Of all the places we visited that day, this one was the humblest. It was a split level house that must have been modern when it was first built back in the 1960s.

The studio is located in the front of the house. Except for a portrait of a client in one corner, none of his original paintings are on display. But you can still see bits and pieces of his career, such as the National Artist medal and some of the works he did designing costumes for Manuel Conde’s “Genghis Khan.” Perhaps, it was tiredness, but I felt sad that for a man who had accomplished a lot, his achievements are summed up in just one room.

Because we just came from the Blanco Museum, we asked Owen if perhaps Botong trained his own son to be an artist. Owen said he did. But while the son did have some talent, he felt he could not grow out of his father’s shadow, so he decided not to pursue it.

Owen added that Botong’s grandson, Carlos Totong Francisco II, did decide to take up art as a career. His gallery is located next to his grandfather’s studio. He made the decision to pursue his own style and not copy the works of his grandfather, which is how he was able to make it in the world of art.

By the time we left the Botong house to get back to the bus, we were all physically tired. But still my soul was full and contented from all the cultural feasting that day.

Hopefully, one day I can return to Angono (home of two national artists, Botong Francisco and Lucio San Pedro) and the rest of Rizal province to explore more of its art, history and heritage.