Rare are the friendships that weather the good times and bad, bringing friends through thick and thin and last more than a millennium.

Such is the historical friendship between the Philippines and China, a relationship that has been chronicled as early as the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Exchanges existed at all levels, from vibrant trade to warm visits between kings and emperors.

Ancient maps, travel journals, poetry, China’s dynastic annals, customs records, all point to an enduring amiable relationship between the two countries, says Carmelea Ang See at the recent Carlos Chan Lecture Series, kicked off in Xavier School, San Juan on Feb. 9. It was held after the annual meeting of the Philippine Association for Chinese Studies.

She is president of Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, a socio-cultural nongovernment organization, and a faculty member at the College of Education of De La Salle University.

The amiable relationship and mutual care for each other’s people in times of emergency – such as typhoons and shipwrecks – are clear in ancient Chinese records, she said.

Shipwreck and rescue

During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), provincial records said Fujian’s prefect praised the Sulu king in 1740, and rewarded him for taking care of 25 traders from Hai Teng county, swept away by strong winds. The king gave his protection and sent his own boatmen to escort the shipwrecked traders back to China.

The following year, the governor of Guangdong province reported that a boat from Luzon had been swept ashore. He gave the typhoon victims food and shelter until the weather improved before sending them back. Since then, any foreign vessel swept ashore was given aid, the crew fed, the boat repaired, until they could return home.

In 1743, the Sulu king sent tribute to the Chinese emperor Qian Long, saying he would like to do so every three years instead of five. The emperor cordially replied that every five years was sufficient. Because the tribute was sent in the summer, the emperor ordered ice and cooling foods to be served, and that a doctor summoned to see to the travelers’ well being.

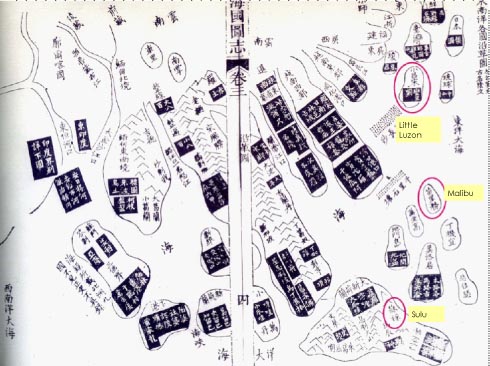

Sulu included in an Chinese old map.

Maps, trade journals

The 16th century Selden Map shows trade routes between China and its southeast Asian neighbors, clearly showing the Philippines, from Ilocos Norte to Manila Bay. Names of places were of Hokkien terms, and included references to 化人住, or “where the Spanish live.”

The term 化人 (huàren) as reference to the Spanish is unique to Chinese living in the Philippines at the time. It is not used anywhere else in the world.

Ancient Chinese records and travel accounts mentioned major points in the Philippines: Luzon, Pangasinan, Mindoro, Cebu, Mindanao and Sulu.

Nearly 400 entries in 83 books during the Song, Yuan (1271-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties mentioned Luzon, Sulu and maritime routes. Travel accounts of the Philippines included the Zhu Fan Zhi (諸蕃志 Records of Various Barbarians) in 1225 by custom collector Chao Ju Kua; Dao Yi Zhi Lue (島夷志略 Tales of the Barbarian Isles) by Wang Ta Yuan, 1345; and Dong Xi Yang Kao (東西洋考 An Examination of the East-West Ocean), 1617.

An Yan Chun, An Jin Tian and Wen Hai Jun pose beside the tomb of the first sultan of Sulu Rajah Baginda at Bud Datu during their historic visit to Sulu, their lao jia (ancestral home), in 2005.

Romance of Sulu

Sulu had a long tributary relationship with China: 16 missions in all to China, spanning two dynasties – 346 years – from the Ming to Qing.

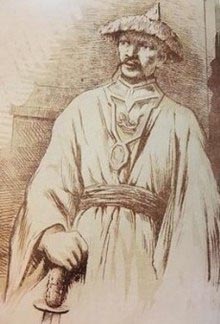

One of the most celebrated stories was the visit of Sulu King Padukah Batara to the Yongle Ming emperor in 1417. This was 100 years before the Spanish arrival in the Philippines in 1521.

Volume 325 of the Ming Annals documented how the Sulu Sultan and his entourage, including two other sultans, paid tribute to Ming Emperor Yongle in Beijing.

The sultan arrived bearing gifts of a memorial inscribed in gold, precious stones, pearls and tortoise shells. In return, he and two others received royal seals and investments as princes of the realm. When it was time to leave, the emperor gifted him with silk, horses, chinaware, court costumes, horses, coins and more than enough gold and silver to get home. He died in Dezhou, Shandong province on the return journey. He was given a royal burial by the Emperor, who reportedly grieved over his demise.

Chinese records showed in detail his path to Beijing, from his landing in Quanzhou, Fujian to the Grand Canal and finally to Beijing. There is speculation that the sultan set out from Sulu and sailed on calmer waters along the Indonesian coast to reach China.

His wife and two sons stayed to observe the traditional Chinese three-year mourning period. The family and its entourage were given accommodation and pensions. They stayed on afterward as state guests, and intermarried with Chinese Muslims.

More than 300 years later, the sultan’s descendants applied for Chinese citizenship in 1731 and their assimilation was complete. Today, there are 3,700 descendants over 21 generations in Dezhou and across China.

In 1726, Emperor Yongzeng of the Qing Dynasty entertained Mohammad Alimuddin, yet another Sulu king, who arrived in Beijing by way of Quanzhou in 1726 bearing gifts.

Qing Veritable Records document 29 noted that a state banquet welcomed the guests. Upon their departure, they received lavish gifts including silk, cotton and brocade.

The visit happened shortly after Spain’s three attempts to attach Sulu: in 1721, 1722, 1723. Alimuddin asked the Qing Emperor’s protection against the Spaniards.

Qing Dynasty annals described Sulu’s people as “good fighters. (Spain) tried her best to make Sulu one of her protectorates but Sulu refused. Though the Spaniards dispatched troops to conquer her, they were defeated.”

Limahong: fugitive or invader?

The story of Chinese pirate Limahong (林阿鳳/林鳯) in 1574 is one that is firmly ensconced in Philippine history books, with accounts of battles between him and Spanish troops. He was wanted in China for his crimes.

But information from more research raised questions about his motives for coming to the Philippines. Did he come to the Philippines to wrest control from the Spaniards? Or was he seeking refuge for himself and his people?

When he and his followers set sail to Luzon, he had with him women, farm implements, furniture, domestic animals, seedlings and plants. Hardly the tools of warfare.

Koxinga, Chinese massacre

Zheng Chenggong (鄭成功 1624-1662) was a Ming loyalist in the dynasty’s waning days, as the Manchus advanced to establish the Qing Dynasty. Known by his Hokkien honorific Koxinga (國姓爺), Zheng Chenggong was incensed by news of a Chinese massacre in the Philippines by the Spanish authorities. He planned to invade Manila in retaliation against the Spaniards. His sudden death prevented the attack.

The threat of an invasion by Koxinga led the Spanish to massacre more Chinese in Manila’s parian, believing that there was a Chinese plot to take the city, and that the men would help Koxinga.

Hearts connected

The serene presence of Sulu Sultan Paduka Batara’s tomb in Dezhou, now a national heritage park, continues to remind people today of the friendship that has existed more than a millennium.

In 1988, the tomb was designated a national heritage site, and funds were allotted to renovate its surroundings. The area was expanded into a heritage park in 2002. An arch – with the words “The Royal Tomb of the King of Sulu” – was erected at its entrance.

From 2014-2016, special envoy to China Ambassador Carlos Chan donated funds for more renovations to the tomb, the Dezhou Museum of Sulu culture, the Muslim mosque and relandscaping of the surrounding area.

In a 2015 visit to the Philippines, one of the Sultan’s Dezhou descendants told local media she was aware of the tiff between the two countries over maritime territories. An Jing said friendship will win in the end, because “our hearts are connected.”