One reason I love visiting historical houses is the fact that I always learn something from the visits. By carefully studying their architecture, the houses’ interiors and contents, the lives of the people that lived there and the times they lived in can be discerned.

Such was the case when I recently visited Mira Nila on Mariposa Street in Quezon City. Built during the country’s Commonwealth period, it offers a fascinating insight into the lives of the elite Filipinos at that time. The house was built by Conrado Benitez and his wife Francisca.

Benitez was a former dean of the University of the Philippines College of Business Administration. He was also one of the men who helped draft the 1935 Philippine Constitution.

Francisca, also an educator, was equally a formidable character in her own right. At a time when women were not yet allowed to vote, she helped co-found the Philippine Women’s University in 1919.

She began building her dream house after a return trip from Europe in 1929.The couple bought a three-hectare land in New Manila, a newly developed area which was considered outside of Manila during that time.

In fact, Quezon City was not even founded yet. According to the house’s curator and Benitez’s granddaughter, Purissima (Petty) Benitez Johannot, one could see the skyline of Manila from

their property when the house was first built.

And this was how the house got its name. Mira, meaning to see in Spanish, and Nila for the city of Manila, Francisca was inspired by the houses she saw from her Florence, Italy trip. She brought home armloads of magazines with the designs of houses she had admired there. With the help of an architect cousin, she came up with a design for her dream house.

I found her choice of architectural style interesting, as during that period, there was another style of décor theme that was popular: Art Deco. It is characterized by its use of lines, geometric patterns and stylized interpretation of nature.

Popularized by the movies and other forms of media then, this was the style that people of the 1920s and 1930s favored to convey that they were modern and fashion forward. But Francisca eschewed the Art Deco theme, favoring the Florentine style from the Renaissance period architecture.

But though the house is conservative in looks and décor, there were a number of features that was innovative for its time.

For example, in contrast to houses built a decade earlier like the Bahay Nakpil-Bautista in Quiapo, Mira Nila was an early example of people utilizing the ground floor of houses as part of their living space.

Prior to the 1920s, the ground floors were regarded not suited for living. During that period, most bahay na bato ground floors were used as storage area, garage, retail space, or housing for servants.

Another is the absence of an entresuelo, a popular feature in many rich people’s houses in those days. It was an area where visitors were screened and waited before they met the owner of the house.

In the case of Mira Nila, guests were screened at the gate of the compound and then either waited at the porch or were ushered into the living room or sala.

Another major change was the separate sleeping rooms for children. Before, houses usually have only two bedrooms at most and children would sleep in the same room as their parents. It was only by the 1920s that habits began to change and children would sleep in their own separate rooms.

In a way, these changes reflect how America’s cultural

influences slowly dominated the country over that of Spain’s. It reflects how Filipinos adopted the American’s concepts on informality, privacy and personal space. Such concepts are still adopted when building our houses today.

Being among the first to move into the area, the Benitez family got the house number 1 Mariposa for Mira Nila.

Their neighbors included prominent people such as Chief Justice Jose Abad Santos and his family, and Rosario Licad, mother of concert pianist, Cecile Licad. Today, the house numbers have changed and Mira Nila is now number 26 Mariposa Street.

As in houses today, the first room I entered was the sala. With its wide space, high ceiling and traditional Filipino wood and wicker furniture, it immediately establishes to visitors a strong sense of solemnity or seriousness. Dominating the whole space are the two portraits above the winding staircase, depicting Francisca at different stages of her life.

Under the staircase is a music alcove, defined by a grand Steinway piano. Above it hangs the portrait of Soledad Francia, Benitez’ mother. The original painting was commissioned by her father, Hilario Francia in 1876. The painter, Antonio Malantic, was one of the best known portrait painters at that time. However, the one that hangs at Mira Nila is a copy: the original is now part of a private art collection owned by the Del Monte Company.

Standing at the corner of the music alcove is a bust of the Benitez couple’s eldest daughter Helena. While the couple had three other sons – Tomas, Alfredo and Angel – it was Helena who rose to prominence. She came to the public’s attention when she followed her mother’s footsteps and served as president of PWU during the 1950s.

It was at this time that she co-founded the Philippine National Folk Dance Company, which introduced Philippine folk dances to the world. This would later become known as the Bayanihan Philippine Folk Dance Company.

This achievement is commemorated by a porcelain figure of a Filipino Muslim princess on top of the piano. Named after the dance Singkil, it was made by the famous Spanish porcelain manufacturer Llandro. It is one of 1,500 limited edition pieces produced by the company.

Helena entered politics in the 1960s. And while her father may have helped write the 1935 Constitution, she served as a legislator in both the Philippine Senate and later the Batasang Pambansa during former president Ferdiand Marcos’ time. She helped pass laws relating to women’s rights and environmental issues.

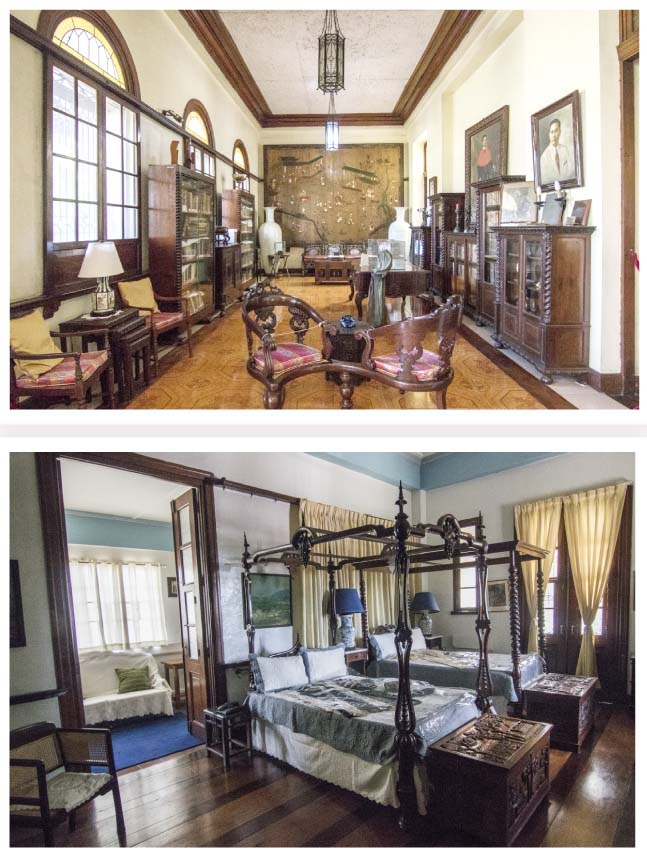

It is obvious that this is a family of intellectual heavy weights. So it comes as no surprise that this house does not have just one, but two libraries. The one on the ground floor features law books and travel books from the 1800s. These belonged to Benitez’ dad, Higino, who seems to be the source of the family’s intellectual DNA, as during his time, he represented the province of Laguna in the Malolos Congress and helped write the country’s first constitution. A portrait of Higino, by another early Filipino artist, Simon Flores, hangs in the library.

During my tour of the house, Benitez Johannot shared that the library’s cabinets and the frame on Higino’s portrait were made by prisoners at the Bilibid prison. Benitez and wife Francisca believed in prison reform, so they commissioned the convicts to build some of the furniture in the house in an effort to help rehabilitate them.

Adjacent to the sala are the dining rooms. The smaller formal dining room featured many fascinating details such as a collection of antique ceramics from China, Vietnam and Thailand that were excavated here in the Philippines. But I was personally drawn to the two carved wooden chairs featuring the seal of Malacañang. These were given to Benitez by then president Manuel L. Quezon.

Benitez and Quezon first met on board a ship when Benitez was on his way back to the Philippines after finishing his studies in the United States. Benitez Johannot shared that the two had a close working relationship and it was also in this dining room that Benitez formed the Citizen League for Good Government in the 1960s in order to help fight corruption in the Quezon City government.

The adjacent room features the bigger dining room. A more recent addition to the house, it was built to accommodate the growing Benitez-Tirona clan. This room featured three tables that could accommodate up to 40 people.

The center piece of the room is a mural by National Artist Carlos “Botong” Francisco called “Binasuan,” which was done in the style of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Surprisingly, Rivera has one of his paintings, “Head study of a Mexican peasant,” hung in this room as well.

In my opinion, the larger dining ought to be called the Latino Room, since this is where Helena’s collection of pre-Columbian terra cotta pottery are also on display. She used to visit Mexico regularly to attend meetings of the International Association of Universities as a member of the board. Afterwards, she would visit prestigious galleries like Sotheby to add to her collection.

Benitez Johannot related that it was in this dining room that the Department of Foreign Affairs used to have their final exams for future diplomats in the 1960s. Helena herself would organize these exams and invite candidates to a dinner party at Mira Nila.

Here they would be graded not only for their speaking ability and general knowledge but

also on things like table manners and grooming. She recounted how one diplomat failed because he brought his girlfriend to the dinner. It was a point raised against him because the examiners thought it was a wrong choice to bring someone with whom he had as yet no definite commitment.

During my visit, I also noticed that there were wrapped Muslim brassware in the dining room. The curator said these were going to be part of a gallery they were setting up in the side patio. It will showcase all the gifts that the Benitez family received from Mindanao royalties. The reason for this was that PWU was non-sectarian and privately Filipino owned. Because of this, the royal families from Mindanao felt that it was safe to send their daughters to study there.

From the large dining room, we climbed the back stairs near the kitchen to the second floor of the house. It was also there where we saw the small elevator that Helena used in her old age when she was not as mobile anymore. Still, according to those who knew her before she died, she was still lucid and could hold a conversation, even though she was already 100 years old.

The main room on the second floor is the house’s second library with 3,450 books. The room also features paintings by famous National Artist Fernando Amorsolo, as well as works done by family

members. In the corridor behind the library are photos of the family with various historical personalities such as Chief Justice Jose Abad Santos, Quezon and Gen. Douglas McArthur.

The bedrooms are also on the second floor. It is an interesting study in contrast as Helena’s bedroom reflects her cosmopolitan taste with 1950s cabinetry and her collection of Russian and Greek icons. Her parent’s bedroom, on the other hand, seems to reflect their provincial gentry’s background with its carved four poster bed and heavy wooden cabinets.

A flight of stairs next to the parent’s bedroom leads to the tower of the house. Helena was 18 years old when she first moved into the house. She loved to climb up to the tower and gaze at the stars. During one of those times, she caught sight of the fire that destroyed Ateneo de Manila campus in Intramuros. Thinking it was the city itself that was on fire, she yelled out to her family “Mira a Manila!” (Come and see Manila), which was supposedly how Mira Nila got its name.

Even before Helena passed away in 2016, the Benitez-Tirona clan had begun thinking of how to preserve the house and its memory. In 2011, the family managed to get the National Historical Commission to declare the house a heritage site. After Helena passed away, it was agreed that the owners of the house would be turned over to the Benitez – Tirona – Mira Nila Foundation. It was also decided that the house would be opened to the public as a memorial. The plan was to eventually turn the house into a museum. Benitez-Johannot said that when they are ready, they will hold guided tours twice a day. The library itself will be opened to the public as a research library.

In what used to be the guest house and storage room next to the house, the foundation decided to convert this into a banquet hall and a café operated by Bizu Patisserie. The former pump house was converted into a gift shop that will offer items unique to Mira Nila. The gardens, pavilion and the outdoor family chapel will also be open to the public which will make for an ideal venue for weddings and other special events.