There are ample historical records of relations between the Philippines and China. They reveal strategies for evangelizing China, trade routes and revolution.

They show the strategic importance of the Philippines to Spanish attempts to christianize China, and to profit from the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade.

They delve into the origins of Chinese-looking Igorots to the north, and names for various farm implements and produce as well as dishes and food habits.

They chronicle alliances between Filipino and Chinese patriots in their struggles for independence from the Spanish overlords in the Philippines, and a rotting Manchu empire in Cathay.

Yes, the records even note the vengeance by Filipinos on the notorious Company C of the Ninth Infantry of the American army for its acts of depravation and atrocities in Eastern Samar, just after doing the same in China.

These were presented by Teresita Ang See in Xavier School, San Juan, Feb. 9 after the annual meeting of the Philippine Association for Chinese Studies.

Her presentation – “Shared History, Shared Heritage, Shared Destiny: Discovering New Narratives on Philippines-China Relations” – was one of two that kicked off the Carlos Chan Lecture Series.

Ang See is executive trustee of the Kaisa Heritage Center in Intramuros, Manila.

Vengeance: Beijing to Balangiga

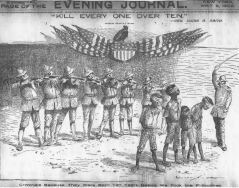

The return of the Balangiga bells in December 2018 is a harsh reminder of American military atrocities in Asia. The church bells were taken as war trophies from Balangiga, Eastern Samar after the United States army, under Brig. Gen. Jacob Smith, set out to raze the town and massacre and rape its people, with the intent to turn it into a “howling wilderness.”

It was in retaliation against Filipino fighters and guerrillas who, armed with bolos, killed 48 of the 74 men in the 9th Infantry. The church bells rang on Sept. 28, 1901 to signal the beginning of attacks by villagers against the American soldiers.

The same US troops from the 9th Infantry had just helped put down the Boxer Rebellion in Peking (Beijing), along with troops from seven other Western powers. The foreign troops committed countless atrocities. They looted, ransacked and ruined Peking and many historical landmarks.

In killing the American soldiers – and taking their weapons and ammunition – the Samareños inadvertently avenged the Chinese killed in Peking.

Headcount

Two Japanese army officers, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, after killing sprees during the December 1937-January 1938 Rape of Nanking (Nanjing) during the Second Sino-Japanese War (July 1937- September 1945), were sent to the Philippines.

They were arrested in Leyte after World War II and extradited to China. They were tried and executed in 1948 for atrocities committed during the Battle of Nanking and the subsequent massacre.

The two had agreed to see who would be the first to kill 100 Chinese with a sword. Mukai killed 106; Noda, 105. Since neither could say who reached the goal first, they agreed to start over again, with the new aim being 150.

A million barbarian souls

Unable to find spices and gold in its early days of occupation, Spain considered abandoning the Philippines. But the priests and traders persuaded the Spanish crown to do otherwise.

“What a glory to God it would be if we could convert a million barbarian souls in Cathay,” suggested Domingo de Salazar, first Bishop of Manila (1579-1584), to King Philip II.

The king likewise heard from Miguel López de Legazpi, first governor of the Philippines (1565-1572).

“If His Excellency minds the China trade, then we have to choose Luzon as our base.”

When they arrived in Luzon, the Spanish found that it was an important base for Fujian merchants trading in the islands, with their wares of spices, silk and brocade.What followed was active exploitation of the Philippines’ strategic proximity to China for faith and profit.

The “History of the Great Kingdom of China” by Juan Gonzales de Mendoza relied on the works of Salazar and reports on the sangleys. Mendoza’s 1585 report is one of the most important works that introduced China to the West. It was eventually translated into seven major European languages and reproduced in 46 editions.

Augustinian priest Martin de Rada visited Fujian in 1574 and kept a journal about his experiences there. One of the first Christian missionaries to visit China during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Rada also brought a lot of books from Fujian – Chinese classics, dictionaries, geography – back to the Philippines.

These were translated into Spanish by Hokkien residents in Intramuros, many of whom were literate.

Spanish priests described Chinese booksellers and bookbinders in Manila. There were books in Chinese: dramas, historical digests, geographical gazetteers, descriptions of foreign countries, and collections of moral sayings.

Four of the six earliest and rarest books in the Philippines were in Chinese letters and language, thanks to the presence of, and help from, Chinese printers and Hokkien literati.

Chinese parishes exposed Spanish friars to Chinese customs, attitudes, values and language.

Miguel de Benavidez, third archbishop of Manila (1602-1605), noted “The Chinese take to their great and true wealth not gold nor silver, nor silk, but books, wisdoms, virtues and just government.”

Exposure in the Chinese parishes also gave them access to people and commerce between Manila and Fujian. The galleon trade (1565 to 1815) sailed from Zhangzhou, Fujian province, passed by Manila, then on to Mexico. Meanwhile, Chinese converts – mainly from Fu’an, Fujian province and Zhangzhou – began to travel to the Philippines for religious studies and eventually to be ordained as priests.

The first bishop of China was Luo Wenzao (1651-1691) of Fu’an, who studied at the University of Sto. Tomas in Manila, and was ordained a priest in the city. In 1649, he traveled to Xiamen with a group of Dominicans from Manila. The group included Francisco Varo, who compiled the Chinese-Spanish dictionary.

Flames of revolution

Two centuries later, the Philippine struggle for independence from Spain (1896-1898) coincided with the work of Sun Yat-sen that eventually led to the Xinhai Revolution (1911) in China, which overthrew the last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Revolutionaries in both events were close contemporaries.

Philippine patriot Galiciano Apacible’s 1902 journal noted that while in Yokohama he lived near Sun, and contact with him was continuous and intimate.

“Every night we dined together in our delegation in the little house of Sun Yat-sen.”

Mariano Ponce, while in Japan, reportedly met with Sun and agreed to send fighting men to China to help in the revolution against the Qing Dynasty.

Emilio Aguinaldo, head of the Philippine revolutionary government, heard that food was in short supply for the Chinese revolutionaries. He ordered Ponce to give 100,000 Japanese yen for expenditures to assist the Chinese cause, and as an expression of solidarity. Sun accepted the donation gratefully.

“The Philippines has become a pioneer of independence in Asia, and serves as a precursor to the attainment of civil rights by my fellow Chinese,” said Chinese reformist Liang Qichao of Aguinaldo’s victory against Spanish rule. “The victory of the Philippines causes Chinese to breathe a sigh of relief and causes Westerners to spit out bile.”

If the Philippines started the anti-American uprising, Sun told Ponce that the former would personally lead a Chinese contingent to fight the Americans in the Philippines. But with the defeat of the Philippine revolt, Sun decided to push the Chinese revolution through first before helping the Philippines.

“If we succeed (in China) and (because of it) the Philippines also achieves independence, it would be a similar victory for us both,” Sun said.

A ship carrying arms procured by Sun had hit some reefs and sunk in July 1899. Disheartened, Galiciano Apacible, the Philippine representative in Hong Kong, wanted to kill himself.

Chinese revolutionist Chen Shao-bai talked him out of it.

“Your own life is tied with the survival of the Philippines itself. Do not look at it lightly but guard it preciously for the sake of your country,” Chen said.

Slant-eyed, fair skinned Igorots

After war, there was peace. The Americans used Chinese laborers to build Kennon Road that would connect Baguio City to the lowlands. The result was intermarrying between the Chinese and the indigenous Igorots, leading to progeny with almond eyes and fairer skin.

It was the Chinese too who introduced in the highlands vegetables that are staples in many Filipino kitchens today: togue, pechay, kintsay, upo, sitaw, bataw…

Elsewhere, they introduced commercial farming and sugar-cane pressing, bringing with them agricultural implements and their names, such as the Visayan puthaw for the plow and iron axe, derived from the Hokkien term pothaw.

It is likely that the Chinese influence in farming reaches back further than recorded recent history.

Banaue’s celebrated rice terraces were built using technology from the early Chinese. A visit to the rice terraces in various parts of southern China shows strong similarities not only in the way both were built, but in the surrounding environment and culture as well.

The best reflection of the blending, transformation and indigenization of cultures is in the food preferences and habits, Ang See said. She pointed to the myriad styles of noodles and egg rolls served in Filipino kitchens: pancit canton, sotanghon, pancit luglog, lumpiang shanghai, lumpiang ubod, lumpiang prito and many more.

Names of food made of rice have Chinese names because they were introduced by the Chinese. Examples include biko (rice cake), and bilu-bilo (rice balls).

The Filipino language is rife with words of Chinese origin, from everyday items such as hikaw (earrings) and toyo (soy sauce), to relationships including kuya (eldest brother).

Sharing past, present, future

As neighbors, contact between the Philippines and China is unavoidable. Visits, cultural exchanges, and barter are bound to happen.

Strong comradeship is only natural as people in both countries faced parallel realities: living under the shadow of imperial might, shaking off those shackles through armed revolution, and coping in a world gone mad with war.

Alliances were forged, not just due to exigencies of turmoil, but in peacetime as well in the form of marriage between individuals. These unions provide a natural setting where cultural blending happens easily in so many ways: language, beliefs, food, habits.

As the two peoples look forward to the future, it is good to know that the ties that bind are more solid than any issues today that divide.