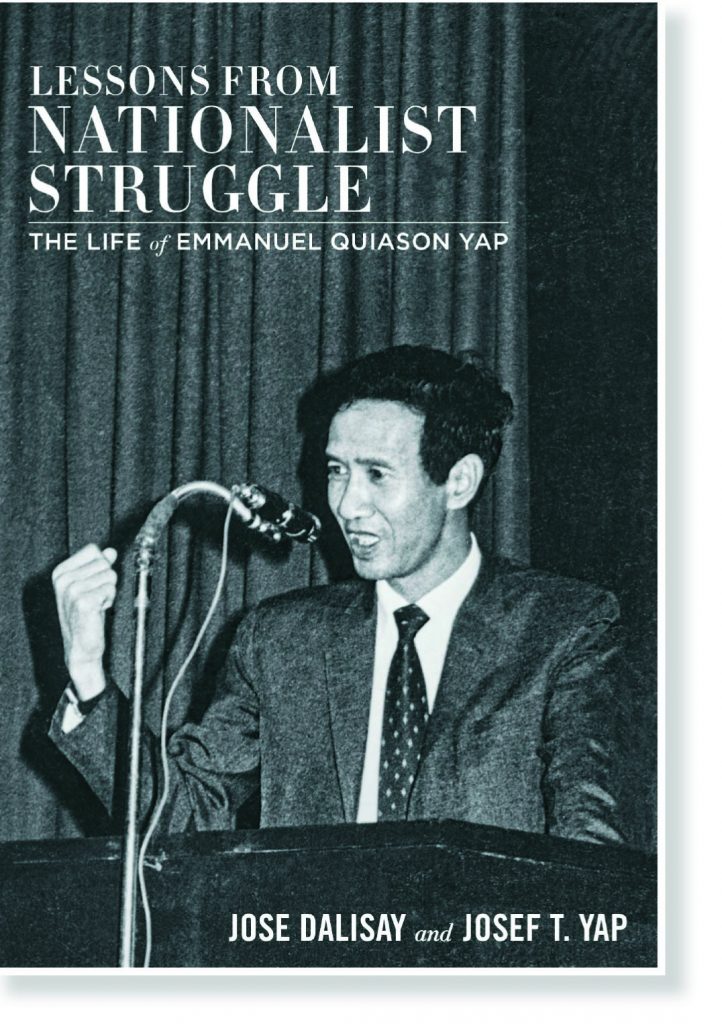

A s its title implies, Lessons from a Nationalist Struggle: Life of Emmanuel Quiason Yap, is a slim biography that hopes to acquaint the reader with a Chinese-Filipino thinker named Emmanuel Quiason Yap or Manoling.

A s its title implies, Lessons from a Nationalist Struggle: Life of Emmanuel Quiason Yap, is a slim biography that hopes to acquaint the reader with a Chinese-Filipino thinker named Emmanuel Quiason Yap or Manoling.

A great leader, influential speaker, problem-solver, Manoling dedicated his life to promoting nationalism and advocating genuine regard for his countrymen, especially those who suffered abuses at the hands of the few. His life would serve as an inspiration or role model to others who share his vision on nationalism.

Lessons from a Nationalist Struggle attempts to shed light on certain dark areas and dilemmas that encumbered the man. Likewise, there are ideas and insights into socio-political realities relevant today that may be explored and examined by the serious student of history and discerning readers.

Co-written by Josef Yap, Manoling’s son, and Jose Dalisay Jr., a prominent Filipino writer, the book is divided into three major chapters.

The Yap family may have chosen Dalisay because of the latter’s own work on the biography of the Lava Brothers, who were personally known to and closely associated with Manoling.

Moreover, Dalisay was a teacher to one of Manoling’s children. According to his family, Manoling had initially intended to write his biography – and he would have done well because of his outstanding prose – had he not died early due to diabetes complications.

When he was an Ateneo freshman, his essay on the Filipino peasants titled “Peace on Earth” won first prize in a writing contest and was published in The Ateneo Quarterly.

His life

The reader sees the young Manoling especially in his teenage years displaying remarkable concern for the plight of the poor. As a young man brimming with energy and enthusiasm, it was easy for him to pacify disagreements or resolve conflicts.

He possessed such persuasive power even at such a young age. The popular painter Daniel H. Dizon, who was a very close friend of Manoling, gives a glimpse of his childhood persona: “Because Manoling had an infectious physical energy, I eventually got interested to play outdoor games like patintero, hide-and-seek and marbles.”

Chinese roots

Manoling’s grandfather, Jose Carlos Yap Siong, left Fujian, China to settle in Angeles, Pampanga and married Maria Lim Lao who gave birth to their only child: Jose Lao, Manoling’s father. An old family portrait shows Yap Siong and Jose Lao wearing a queue, a symbol of Manchu dominance in China.

According to Josef, Manoling’s travel to China sometime between 1967 and 1972 may have influenced him to help strengthen diplomatic ties between China and the Philippines, and craft a better foreign policy with Leticia Ramos Shahani. He aimed to crush any romantic notion between the United States and the Philippines, which was the prevailing sentiment then – and even until now.

His career

This chapter discusses Manoling’s early political inclination, and his close connection with the Laurel clan, starting with President Jose P. Laurel. He was given opportunities to grow and promote nationalism at the Lyceum University where he was able to explore and expand his vision.

Even during this early stage in his career, he was already aware of the dangers of colonialism and how it strangled the Filipinos. He was unfairly labelled a communist, because of his ability to straddle the often warring divisions of politics.

The reader might also be shocked to learn that Manoling was said to have held President Marcos in high regard, believing that he was an ardent nationalist and had vision, but that Marcos unfortunately soon fell prey to the claws of the Americans and personal excesses, including the ostentatious lifestyle of Marcos’ wife Imelda Marcos.

Another surprising revelation is Manoling’s disapproval of his cousin Ninoy Aquino’s decisions. Though he was always there whenever Ninoy asked for his advise, he was wary of Ninoy’s motives – especially after the latter admitted that he was working with the Central Intelligence Agency.

To him, Ninoy and Cory Aquino were players on the side of the Americans in its political game. The EDSA Revolution was not a Filipino achievement but that of the US. Moreover, Cory was cast in a bad light when, after toppling Marcos, she did not step down in two years – the second platform element of her party UNIDO, as she had promised to do – but held on to power until 1992 instead.

His legacy

But the most important part of this biography focuses on the legacies: his intellectual output, writings, and actual work. Very few know that he instituted the CEPO (Congressional Economic Planning Office), the House of Representatives’ think tank during Speaker Jose B. Laurel Jr.’s term which, after several reorganizations, has turned into what is now known as NEDA (National Economic and Development Authority), the agency chiefly responsible for planning the country’s economic activities.

Another long-lasting legacy of Manoling is his contribution to the national effort of fostering ties with socialist countries. He was instrumental in drafting a foreign relations policy with the Asia Pacific when he worked with Leticia Ramos Shahani, who herself had extensive experience in foreign relations.

Despite Manoling’s early admiration for the progressive and nationalistic character of Marcos, he remained objective: he did not fail to see his abuses and excesses. He founded the People’s Patriotic Movement, which hoped to inspire, promote and rekindle nationalism among Filipinos. Such an aspiration lines him up with nationalist intellectual heroes like Mabini and Rizal.

Other equally noteworthy accomplishments, such as his role in the modernization of Angeles City, places Manoling in the hallmarks of history, as a beacon of hope, an icon of a true nationalist, patriotic thinker and leader.

Unfortunately, most of his dreams didn’t see fruition. Worse, he died early due to long-term diabetic complications, a disease which had also afflicted his father. He was frustrated by the nonsense quarrels, by the personal and political ambitions of most people whom he initially thought would be cooperative, and whom he thought shared his nationalistic fervor.

The book’s purpose

What this biography hopes to achieve is awaken the heart and mind of the astute reader, that they might hopefully learn and pick up where the visionary Yap had left off, and turn into reality those dreams still waiting to be fulfilled.

His words ring true even now: “We Filipinos should know the historical truth, put aside our petty bickerings and superfluous differences, foster a spirit of national solidarity, make the necessary sacrifices, and vigorously move to build a strong, progressive nation-state.”