Vaccines protect children from a variety of serious or potentially fatal diseases, including diphtheria, measles, polio and whooping cough (pertussis). If some of these diseases seem uncommon — or even unheard of — it’s usually because the vaccines are doing their job. Still, you might wonder about the benefits and risks of childhood vaccines. Here are answers to common questions about childhood vaccines.

Vaccines protect children from a variety of serious or potentially fatal diseases, including diphtheria, measles, polio and whooping cough (pertussis). If some of these diseases seem uncommon — or even unheard of — it’s usually because the vaccines are doing their job. Still, you might wonder about the benefits and risks of childhood vaccines. Here are answers to common questions about childhood vaccines.

Is natural immunity better than vaccination?

A natural infection might provide better immunity than vaccination – but there are serious risks. For example, a natural chickenpox (varicella) infection could lead to pneumonia. A natural polio infection could cause permanent paralysis. A natural mumps infection could lead to deafness. A natural measles infection could result in permanent brain damage. Vaccination can help prevent these diseases and their potentially serious complications.

How do vaccines work?

Vaccines work by making us produce antibodies to fight disease without actually infecting us with the disease.

If the vaccinated person then comes into contact with the disease itself, their immune system will recognize it and immediately produce the antibodies they need to fight it.

For a short period, lasting a few months, newborn babies are protected against several diseases, such as measles, mumps and rubella, because antibodies have passed to them from their mothers through the placenta. This is called passive immunity. This is why the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella or German Measles) vaccine is given to children around their first birthday and not earlier.

Do vaccines cause autism?

Vaccines do not cause autism. Researchers have found no connection between autism and childhood vaccines. In fact, the original study that ignited the debate years ago has been retracted.

Are vaccine side effects dangerous?

Any vaccine can cause side effects. Usually, these side effects are minor — low-grade fever, fussiness and soreness at the injection site. Some vaccines cause a temporary headache, fatigue or loss of appetite. Rarely, a child might experience a severe allergic reaction or a seizure. Although these rare side effects are a concern, the risk of a vaccine causing serious harm or death is extremely small. The benefits of getting a vaccine are much greater than the possible side effects.

Of course, vaccines aren’t given to children who have known allergies to specific vaccine components. Likewise, if your child develops a life-threatening reaction to a particular vaccine, further doses of that vaccine won’t be given.

Is it OK not to get my child vaccinated?

It is not a good idea to withhold vaccines from your child. This leaves your child vulnerable to potentially serious diseases that could otherwise be avoided.

If you have reservations about particular vaccines, discuss your concerns with your child’s doctor. If your child falls behind the standard vaccines schedule, ask the doctor about catch-up immunizations.

How long does protection last?

Some vaccines provide very high levels of protection – for example, MMR provides 90 percent protection against measles and rubella after one dose. Others are not as effective – typhoid vaccine, provides around 70 percent protection over three years.

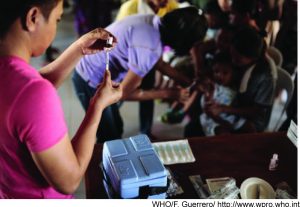

How does a public vaccination program work?

When a public vaccination program is introduced, everyone in the population of a certain age or risk group is offered a specific vaccine to try to reduce the number of cases of the disease. They often concentrate on young children, as they are particularly vulnerable to many potentially dangerous infections.

When a vaccination program against a disease begins, the number of people catching the disease goes down. As the threat decreases, it’s important to keep vaccinating, otherwise the disease can start to spread again. If enough people in a community are vaccinated, it’s harder for a disease to pass to people who have not been vaccinated. This is called herd immunity.

Herd immunity is particularly important for protecting people who can’t get vaccinated because they are too ill or because they are having treatment that damages their immune system. The more infectious the disease, the greater the number of people who have to be vaccinated to keep the disease under control. Measles, for instance, is highly infectious. If vaccination rates go down, measles will quickly spread again. We know that at least 90 percent of children have to be immune to stop measles from spreading.

Are there vaccines for adults?

It is not only children who need vaccines to prevent them from getting certain infectious diseases. In another column, we will discuss vaccines for adults.

Categories

Common questions about childhood vaccines