First published in Tulay Monthly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 1, no. 6 (November 13, 1988), p. 10.

November 1, All Saints’ Day, the day when we revisit the dead. The endless miles of people trekking to the cemeteries and parks is an all-too familiar scene.

The Chinese cemetery situated in La Loma is no exception. On this day, the whole cemetery comes alive and throbs with bustling activities. Generally, there is an air of festivity as relatives bring food, paper money, candles, incense as well as other miscellaneous items needed to render proper mourning to their dead ancestors.

Small wonder then that people generally perceive this day as a day for socializing. The act of incense-exchange and/or candle-exchange where l-burn-candles-for-your-dead and you-burn-candles-for-mine becomes an occasion for renewing old friendships and tics, not just a performance of a traditional rite or obligation. Often, friends and relatives who have not seen one another for the whole year go “grave-hopping,” mainly for socialization purposes.

The elaborate edifices provide temporary relief from the sun and a resting place for the people as they “visit” one grave to another to pay their respects to the deceased. They burn candles, incense and paper money in the prescribed manner, then settle down to enjoy the food after having “offered” it to the dead.

These are the activities that people usually witness at the Chinese cemetery on All Saints’ Day. Many are acquainted with the rituals that the Filipino Chinese adapt, but few really know why these rituals are being observed.

The rituals observed by the Philippine-Chinese on All Saints’ Day and on other occasions when homage for the dead is called for are practiced in line with ancestor worship. Although ancestor worship among the Chinese is not a religion, the practice of its rites in itself is akin to religion because of its pre-dominance in the Chinese way of life.

The Confucian doctrine “the benevolent man loves others” is usually interpreted in the light of filial piety to the effect that the “benevolent man loves others, with his own parents as the starting point.” It is popularly believed that people who fail to remember their dead ancestors will have cursed lives.

For the Chinese (as it is for other races), there are four precious moments in a man’s life: birth, coming of age, marriage, and death. These are not merely individual experiences, rather, these are important moments connected with the religious aspect of the family. All of them derive importance from their connection with the basic duty of filial piety (孝).

Filial duty involves paying due respect, not only to one’s living parents, but also to the deceased and to remote ancestors. Therefore, ancestor worship takes place as a natural consequence of paying tribute to one’s parents. This requires the children to devote themselves body and soul to the care of their parents and to provide for a grandson who would carry on the ancestral sacrifices.

Ancestor worship has been a paramount pre-occupation because this molded the family and clan, and hence the Chinese society. Filial piety constitutes the cardinal virtue and is the basis for family governance. The ancestors confer blessings or send disaster according to the behavior of their descendants.

Death for the Chinese is but a normal and integral flow of the family life. Death rituals are important in Chinese religion. They are protracted and momentous and are carried out in three stages: the funeral, mourning, and continuing sacrifices to the dead.

An old person is assured of a proper funeral, proper reverence and remembrance after death by his descendants. His spirit is present in the family altar, where it receives daily gestures of remembrance, such as offerings of food and wine and the burning of incense.

(From Tulay Files)

The burial rites have to be done right for the contentment of soul of the person. A wrathful soul, kuei (鬼), meaning ghost or demon, endangers the health, happiness and prosperity of those who offend it.

The grave itself has to be situated auspiciously according to the lore of geomancy (feng shui 風水). Several times a year as directed by the annual calendar of religious festivals, services of remembrance are held, or visits made to the graves by the family members.

It is also believed that the deceased’s soul spends seven weeks (49 days) on a dangerous and difficult journey to his afterlife, and so during this period prayers and sacrifices are especially necessary to assist it. For this purpose, formal memorial services are conducted by both the Buddhist and Taoist priests, and occasionally, Catholic priests are called in to say masses.

These offers of sacrifices and prayers for the dead are connected with the Chinese concept of the after-world. The Chinese do not have the equivalent of purgatory or hell — their after-world is in the here and now.

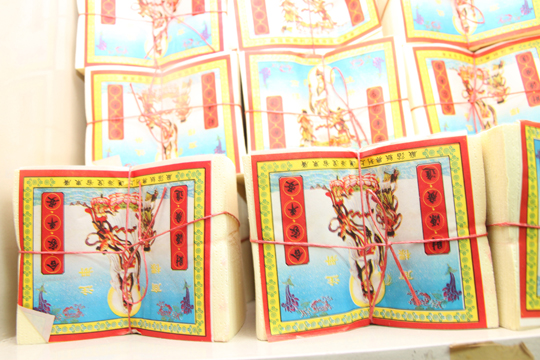

Hence, food is offered, paper money and incense burned, paper houses, cars and the deceased’s paraphernalia are also burned in the burial site so that the deceased have something to use in his afterlife.

(Photo: Anson Yu)

(Photo: Anson Yu)

This preoccupation with ancestor worship is also the main reason why the local Chinese have built elaborate and magnificent edifices for their dead. The traditional Chinese believe that the more elaborate or lavish a funeral is, the more one can show his reverence or respect for the dead one.

Young Chinese Filipinos often find the rituals and the practices cumbersome and impractical. Few can understand what each stage of the death rites means. Many opt to follow Catholic or Christian burial rites which are simpler and more meaningful to them. Because the Chinese cemetery have become overly crowded, many also opt to bury their loved ones in the airy and spacious expanse of memorial parks where the graves are simpler and more dignified.

In whatever manner the death rites are observed, the main sentiment underlying ancestor worship is the Chinese’s commemoration of one’s origin – the fountain of his life – and in repaying the debt that he owes to his ancestors.

At the same time, these rituals of worship also involve praying for blessings. As Confucius once put it, “When I wage war, I will win the victory and when offering sacrifice, I will gain blessings because l have practiced the right way.”