China is a country of festivities. Each particular occasion demands its own corresponding celebration.

There are at least six “Great Festivals” to break the monotony of the Chinese everyday life: New Year or Spring Festival (1st day of 1st month), the Lantern Festival (15th of the 1st month), Festival for the Dead (5th of the 4th month), the Dragon Boat Festival (5th of the 5th month), Brotherhood Festival or Festival of the Ghosts (15th of 7th month), Mid-Autumn Festival or Moon Festival (15th of the 8th month).

The Chinese uses the lunar calendar, with the counting of days based on the revolution of the earth around the moon, not the sun. Hence, there are 30 days to a month and the 15th of the month is always full moon.

The 8th month is known as Moon Festival because it is the time of year when the moon is at its roundest and its brightest. This year, 2022, the festival falls on the 10th of September.

ln the Chinese mainland, in Hong Kong, and in Taiwan, the Moon Festival is an occasion for a family reunion. The family gathers around to share delectable mooncakes while enjoying and singing praises to the moon’s beauty.

ln Hong Kong, people make special lanterns and bring them up to the terraces of the high-rise buildings so they can watch the moon better. It is said that if you look long and hard enough, you may be able to get a glimpse of the goddess of the moon.

The celebration of moon festival in the Philippines is uniquely Philippine-Chinese. Nowhere else can you find the moon festival being celebrated with such enthusiasm and innovations as in the Philippines.

The Moon Festival celebration has become a major activity for all organizations, of whatever nature, existing in the local Chinese-Filipino community. It is an occasion for class reunion, alumni association reunion, family association and hometown association gathering, brotherhood association meeting, socio-civic club affairs and others.

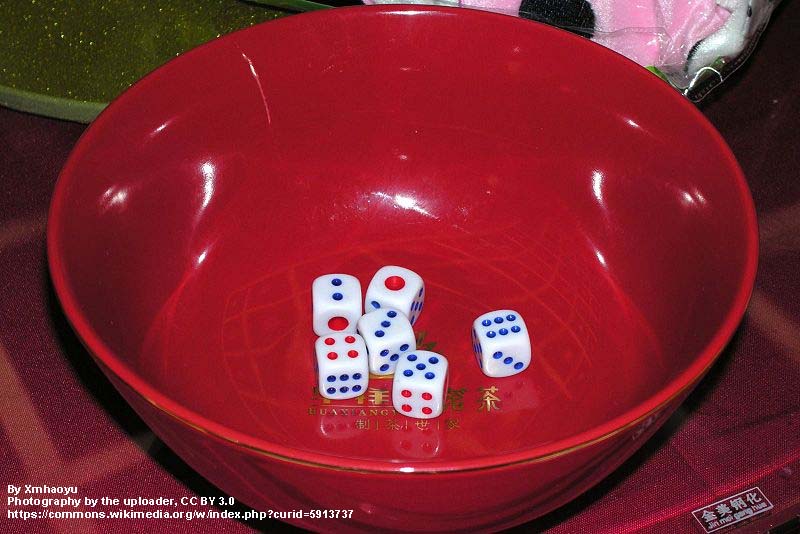

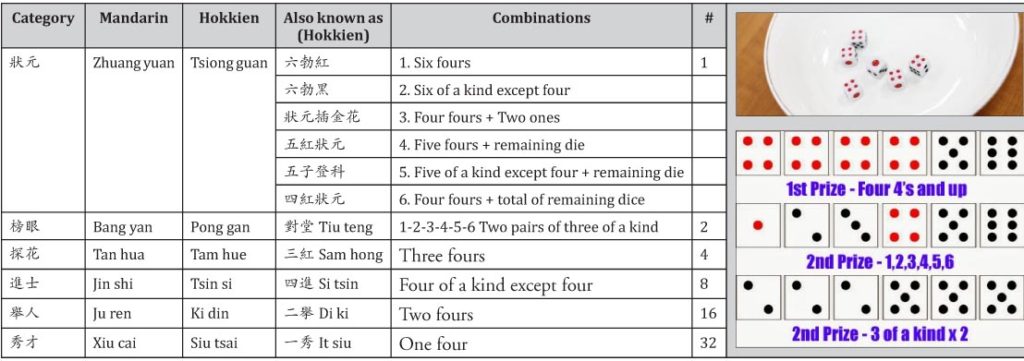

The main (and most of the time the only) feature of the celebration in the Philippine-Chinese community is the Game of Mooncakes, which is essentially a game of chance, played with the use of six dices thrown into a round bowl.

Three things needed in the game are 1) a set of six dice; 2) a deep round bowl; 3) a set of mooncakes, comprised of 63 pieces of mooncakes of different sizes, divided into seven ranks. Each rank is given a corresponding combination of dice. The game is finished only when all 63 pieces of cakes have been taken.

ln innovations of the local Chinese, the mooncakes are substituted with other novelty items like kitchen wares, imported foodstuffs, and others to make the game more exciting. The value of each item increases according to the ranks. ln some associations, the stake for the chiong guan, the highest rank, could be as high as a car.

The cause of the celebration itself is sometimes forgotten in the excitement of the game of chance, but this is true only among the Philippine-Chinese.

Elsewhere, the mid-autumn or moon festival is remembered not just as an occasion for reunions — the round moon symbolizing roundness or togetherness (being whole once more). It is also being observed to remember a significant historical event.

During the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368), when China was ruled by the Mongolians, the traditional mid-autumn festival played a crucial role in the revolt of the Han Chinese against the foreign invaders.

The Mongol ruler, scared of revolts by the Han majority, implemented a rigid rule limiting the possession of knives to one knife per family. The movements of every family were also closely watched.

In order to gather enough weapons and act simultaneously, the patriotic revolt leaders made use of the moon festival by inserting a piece of paper inside each mooncake. The paper instructed the Han people to attack the Mongolian soldier assigned to watch over their household simultaneously at a designated hour.

The revolt succeeded, and this added patriotic color and historical value to the traditional moon festival.

Updated version of the article published in Tulay Monthly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 1, no. 4 (September 11, 1988), p. 11.