Editor’s note: In the Mid-Autumn Festival dice game, the prize categories are named after these examination titles. The first to sixth prize categories are named as zhuang yuan, bangyan, tanhua, jinshi, juren and xiucai, respectively.

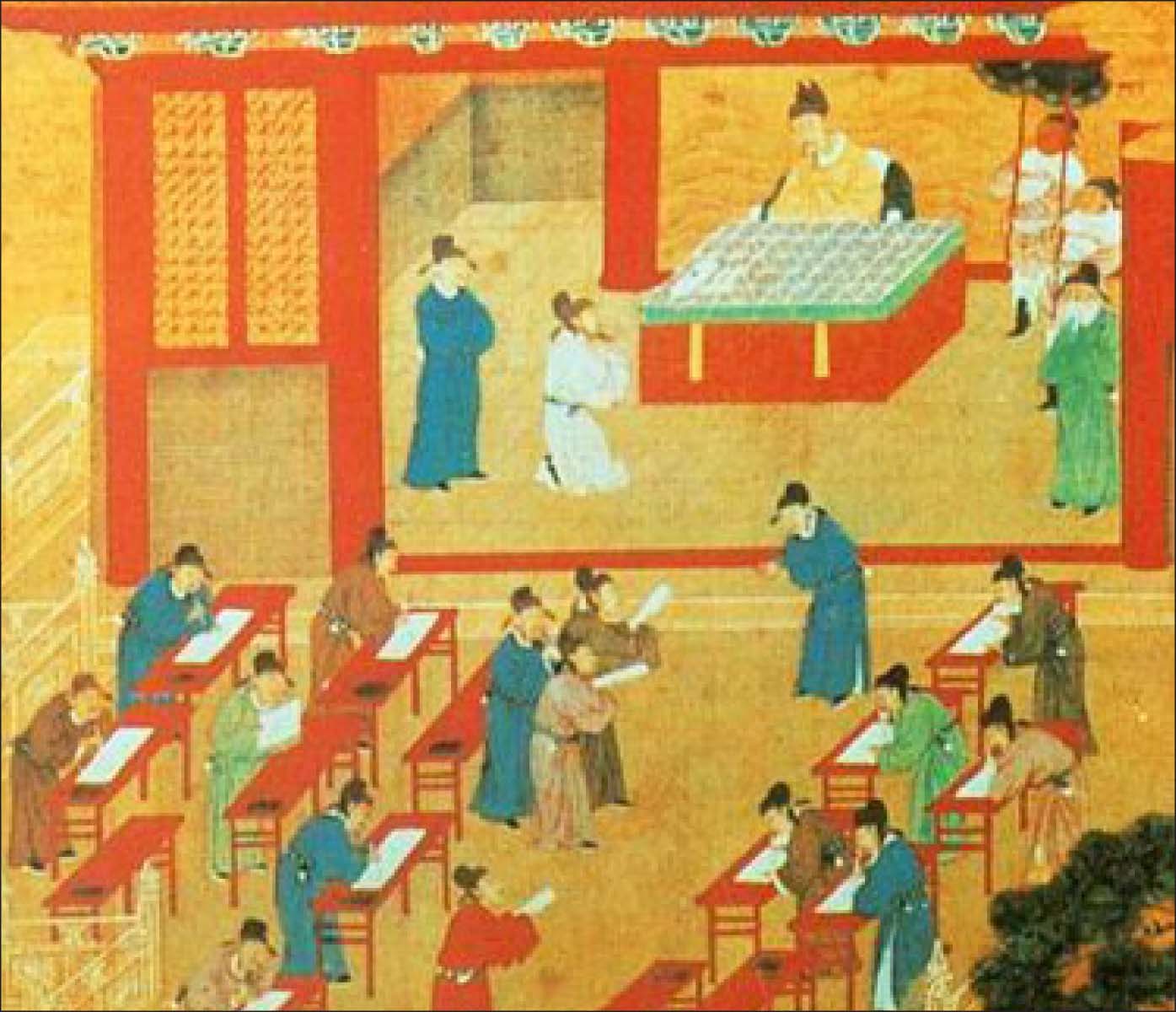

To select capable people to help govern the country, Emperor Wen Di of the Sui Dynasty (581-618) established an imperial examination system to select officials through different types of examinations.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), the imperial examination system was revised. Like officials, the average scholar was now allowed to sit for separate examinations at different levels.

The imperial examinations began at the lowest level – the county, and anyone who passed this examination would be given the title xiucai. At the provincial level, successful candidates receive the title juren. The highest level held at the capital was the metropolitan examination for a jinshi degree, the most coveted since it provided the opportunity to rise high in the official world.

Jinshi was the most difficult title to win, with only one or two in a hundred emerging successful. Many scholars were lifelong failures at this, while others became jinshi only when they were old.

During the Tang Dynasty, all jinshi examinations were held in Chang’an during the first moon, with results known the following month. When spring came and flowers bloomed, the emperor would give a grand banquet in a garden at Qujiang in honor of the new jinshi.

Qujiang was a sizable pond full of twists and turns, around which were built many beautiful gardens, like the grounds of the famous Ci En Si Temple, the Da Yan Ta Pagoda and the Xiao Yan Ta Pagoda (Big and Small Wild Goose Pagoda). The emperor frequently went there with his ministers and nobles, as would men of letters and scholars who liked to have drinking parties and compose poems there.

At the royal banquet, the jinshi would place cups of wine on the surface of the pond and allow them to drift with the currents. Whoever found a drifting cup stopped before him had to pick it up and, sipping the wine, compose a poem.

The two youngest and most handsome jinshi would be sent to search for and gather all kinds of rare and beautiful flowers. Thus, the banquet was dubbed “Flower searching and gathering banquet” and the flower gatherers, “flower searchers.”

The jinshi who top the examination held the title zhuang yuan. The second place received the title bangyan and the third that of tanhua, which means “searching for flowers.” It is likely the title tanhua came from the practice of searching for flowers at Qujiang.

After one such banquet, the jinshi took a tour of the Ci En Si Temple. When they came to the Da Yan Ta Pagoda, one of them, on a whim, carved his name on the stone base of the pagoda.

This eventually developed into a custom. After the Qujiang banquet, all the new jinshi would come over to the Da Yan Ta Pagoda, and an expert calligrapher would be chosen from among them to inscribe all their names on a stone tablet. If one of them became a general or a prime minister, his name, originally written in black ink, would be painted in red.

Through the Tang Dynasty, intellectuals deemed it a great honor to be able to attend the “flower searching and gathering banquet at Qujiang” and the “name inscribing ceremony at the Da Yan Ta Pagoda.”

Over the years, Qujiang was destroyed in wars, but the tradition of inscribing names at the Da Yan Ta Pagoda survived from generation to generation. Even now, on the tablets at the base of the pagoda can be discerned the names of jinshi of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

The Tang examination system which offered scholars an opportunity to participate in the country’s political activities even if they were of humble origin was of positive significance at the time.

As one dynasty followed another, the imperial examination system became increasingly corrupt and degenerated towards the end of the feudal society.

This was especially true of Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties when examinations were confined to such Confucian classics as the Four Books and the Five Classics and the essays required to be written had set forms and many hard-and-fast rules with which the candidates were not permitted to take liberties under any circumstances.

This kind of essay was known as “the eight-legged essay.” Many a scholar in pursuit of official rank and wealth spent their whole life composing stereotyped eight-legged essays.

In Pu Songling’s Tales of Liaozhai and Wu Jingzi’s The Scholars, both of the Qing period, are vivid descriptions of the corruption and malpractices of the examination system at the time. Eventually, the imperial examination system perished with the elimination of the feudal society in China. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 25, no. 8 (September 25-October 8, 2012): 13.