First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 25, no. 4 (July 24-August 13, 2012): 8-10.

Editor’s Note: The paperback edition of the author’s book, Chinese and Chinese Mestizos of Manila – Family, Identity, and Culture, 1860s-1930s, was launched at Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City. The author is Tsinoy who now lives and teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Mass. Yet, his heart lies in the Philippines, land of his birth. He offers this book, hailed as a landmark work that chronicles an important period of the history of Chinese and mestizos living in the country. He shares with Tulay readers the factors leading to the writing of this book, and his future ambitions as he continues to study the dual cultural heritage all Tsinoys share.

I began feeling “different” racially when I went to college. Growing up, I thought I was Filipino.

In my high school days at Xavier School, Greenhills, San Juan, my teachers ingrained in me a sense of being Filipino. Despite my awareness that I was Chinese, I did not feel that I belonged to a racial minority until a Filipino classmate in Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, said I was not Filipino but Intsik.

Since then, I became more conscious of the division between lán-lâng (咱人 Hokkien term Chinese in the Philippines use to refer to themselves and which means “our own people”) and hoan-á (番仔 Hokkien term the Chinese in the Philippines use to refer to Filipinos and which means foreign barbarian).

The desire to understand why such a division existed and to help promote racial harmony between Chinese and Filipinos motivated me to write this book.

But getting from point A (becoming aware of the racial divide in Philippine society) to point B (publishing the book) took several years, filled with many challenges as well as rewards. Certain life events and people who came into my life helped make this book reality.

Awakening

I was a college senior when the People Power Movement (leading to the EDSA Revolution, 1986) happened.

My Jesuit education from grade school to college had instilled in me the desire to be a “person-for-others.” While in Ateneo, I was active in socially-oriented organizations such as Gabay (a scholars’ organization) and theater group ENTABLADO.

When the anti-Marcos movement escalated, I participated in demonstrations, volunteered for election watchdog National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections, guarded the ballots at the Pasay City municipal hall, and camped out in the streets during the EDSA Revolution of 1986.

After graduation, I wanted to continue to serve the country.

One day in 1987, I saw a newspaper announcement about the formation of Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, Inc. I did not lose time joining the group.

Participating in Kaisa’s activities and programs designed to promote the integration of the Chinese into Philippine life provided me a way to continue giving back to Philippine society. But there was also the question of how I was going to fulfill this goal while pursuing a career.

Becoming an academic

Back in college, I already knew I wanted to work in the field of education, even though I came from a merchant family. After college, I taught at Sacred Heart School for Boys in Cebu for a year, then did a two-year stint as an exchange student in Xiamen University.

Back in Manila, I joined Ateneo’s Chinese Studies Program and taught Mandarin. I tried applying to become a Jesuit but was rejected. Consequently, I began seriously considering a career as an academic.

In 1992, I left the Philippines to pursue a Master’s degree in East Asian Studies at Stanford University, Stanford, Calif. While there, I decided to become a historian.

As I searched for a university at which to do my doctorate, historian Dr. Edgar Wickberg (1927-2008) suggested I apply to University of Southern California in Los Angeles, where Dr. John E. Wills Jr., a historian specializing in Chinese maritime history, taught.

Wills, now retired, was professor emeritus at USC’s history department. Wickberg was a noted scholar on China and southeast Asia, and professor emeritus in history at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

At USC, under the able guidance of Wills and other professors, I began my training as a scholar of the history of the Chinese in the Philippines. I read Wickberg’s seminal work Chinese in Philippine Life 1850-1898 and many other works written by Tsinoy scholars such as Chinben See, Antonio Tan and Teresita Ang See.

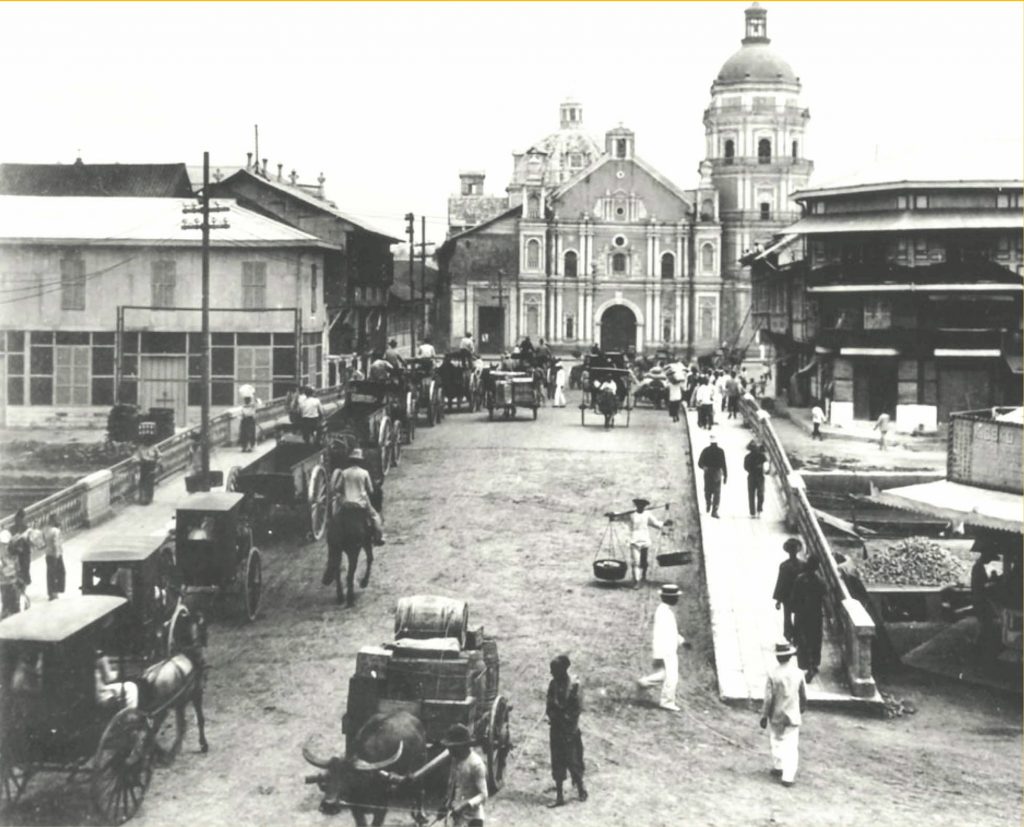

Hence, in my earlier publications and dissertation, I focused on tracing historical roots of the division between Chinese and Filipinos. I decided to concentrate on the period from 1860s to 1930s.

It was during this time most of the ethnic classifications and racial stereotypes in Philippine society were formed.

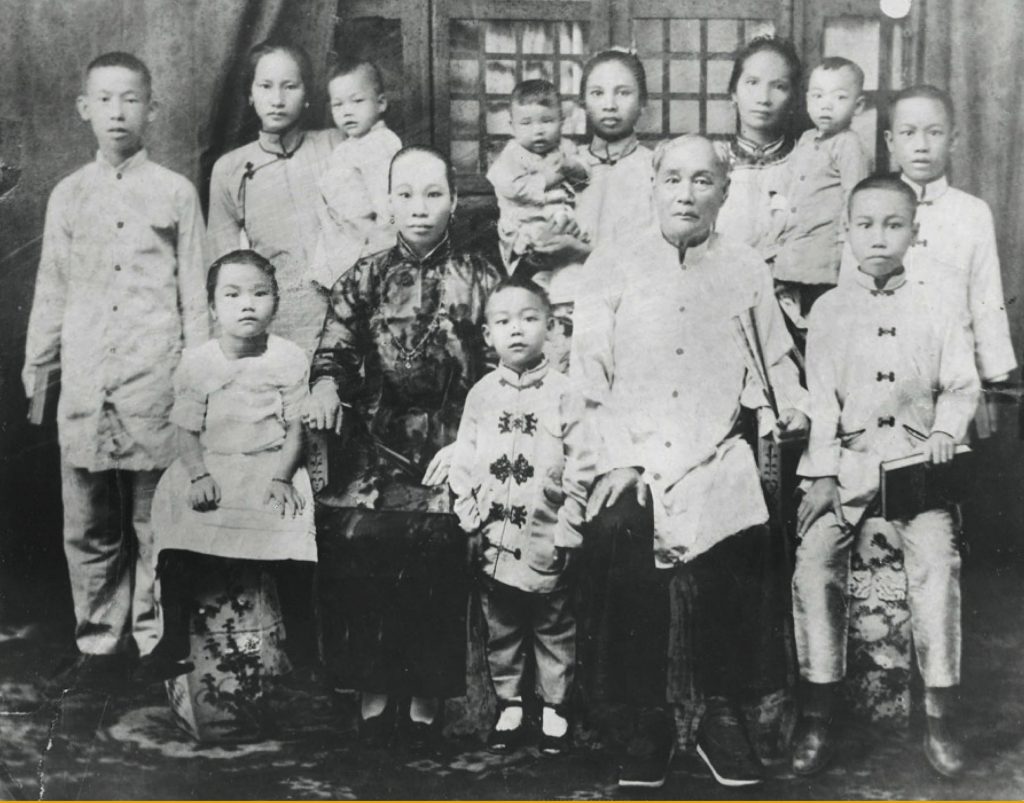

What led these two groups to regard each other as separate? How, as Wickberg claims, did Chinese mestizos who were born of Chinese fathers and Filipino mothers, or those who had Chinese ancestry, later became identified as Filipino and not Chinese?

Furthermore, I sought to understand how individuals and families of dual or mixed cultural heritage understood and lived out their own identities vis-à-vis state-proscribed ones.

I was inspired by Karen Leonard’s study on bi-cultural Punjabi-Mexican families in California. She demonstrated that people, especially those belonging to an ethnic minority, often switched identities depending on their life situations.

The challenge therefore was how to do the research that would allow me to reconstruct the lives of different Chinese and Chinese mestizo individuals and families.

Various grants provided the funding for my research in the Philippines, China and the US. My sources included state and church records, including baptismal and marriage certificates, contracts, court cases, and testaments, found in the Archives of the Archdiocese of Manila, the National Archives of the Philippines, and the Genealogical Society of Utah.

The GSU is run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints of Salt Lake City, Utah. The society collects documents and other materials that may contain biographical information of individuals all around the world.

They microfilmed different sources here in the Philippines, such as baptismal records from the Archdiosean Archives of Manila and notarial records of the National Archives of the Philippines. I pored through volumes of old, many deteriorating, documents, and hundreds of feet of microfilm, searching for names of individuals and families I wanted to include in my study.

During my research and writing, I was also lucky to meet people who willingly shared their own families’ research, such as Raul Boncan and Josephine Khu, descendants of individuals in my book.

Boncan is the great-grandson of Joaquin Barrera Limjap and Ignacio Jao Boncan; Josephine Khu is great-granddaughter of Guillermo Cu Unjieng. My work was also helped along by the very able staff of various archives and libraries and research assistants in Manila.

I am also very thankful to individuals who provided feedback for my research, such as Tsinoy historians Ang See and Go Bon Juan, and most of all, Wickberg, who up to the last months of his life continued to support and encourage me.

I completed my dissertation in December 2003, and became assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where I spent a couple of years turning the dissertation into a book. The book grew from five chapters to nine.

In 2010, Brill Publishers of Leiden, The Netherlands, and one of the oldest and leading academic publishers in Europe and the United States, published Chinese and Chinese Mestizos as the first volume in its “Chinese Overseas” series. Hardbound and priced at US$180 (P7,000), it was circulated among academic circles, but certainly out of reach for most of the reading public.

Today, the paperback edition is finally available at P650 in the Philippines through popular retailers like National Bookstore, Powerbooks and Kaisa office). This is a gratifying development because I had written the book with Philippine readership in mind.

At this price, it is finally accessible to the Philippine audience. I am therefore very grateful to Karina Bolasco, founder and publishing manager of Anvil Publishing, Inc. for agreeing to print a softback version of Chinese Mestizos.

The book’s intent is to help promote racial harmony in our society, and the writing is my act of giving back to the Philippines.

In the book, I showed that ethnic labels such as Intsik, Chinese, Filipino, or hoan-á are constructions and have a genealogy. People create stereotypes of another group of people they wish to control. Hence, as constructions, ethnic categorizations can be challenged, manipulated, or changed.

Writing the book is also my way of sending a message to readers that they too have the power to negotiate their own identities and not be controlled by labels.

Apart from this book and numerous articles, I have also published a smaller book with the University of Sto. Tomas Press – Manila: Chinese Merchants of Binondo in the Nineteenth Century. It is likewise available in local bookstores.

My next book project is an examination of the racial discourses on the Chinese during the early part of the 20th century, with articles in Philippine and US newspapers – even possibly China-based newspapers if I can find them – as my main sources. An examination of details in these sources has led to a fascinating picture of daily life in Manila at a time of great political change and to broader questions related to race, ethnicity, gender and empire.