First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 5 (August 4-17, 2015): 8-9.

Prior to the arrival of Buddhism in China in the first century of the Common Era, the seventh lunar month was already the customary time for praying for the dead.

Taoist rituals already existed for this purpose. As Buddhism inculturated and became a Chinese religion, it expanded Chinese notions of the afterlife, where food, prayers, and other offerings were regularly presented to the souls of ancestors in the belief that they could impart blessings or curses on their descendants.

Buddhism added the ideas of karma and rebirth to the general notion of looking after the dead. The dead now needed not only to be fed but also to be assisted in their journey towards rebirth, especially if they had been reborn as hungry ghosts.

The process of rebirth is very complex.

There are rituals to be carried out for the 49th and 100th days after death, then again on the 25th month or the third year, and annually for as long as there are descendants concerned about caring for the souls of their ancestors in particular, and the dead in general.

One can never know for sure whether the dead have been reborn as dignified ancestors, or as hungry ghosts roaming the underworld, so prayers and offerings do not cease.

It is believed that wherever the dead are in the cycles of rebirth, they benefit from the merits assigned to them as a result of various rituals.

Over time, Chinese Buddhism developed many rituals and liturgies to help the ancestors and the hungry ghosts obtain release from their suffering, including the Release of Fiery Mouths (Fang yankou 放焰口), the Water and Earth Repentance Ritual (Shuilu fahui 水陸法會) and the Emperor Liang Jeweled Repentance (Liang Huang Baochan 梁皇寶懺).

The latter two were commissioned by Emperor Wu of Liang (6th century period of Six Dynasties) after he had dreams that people close to him, including his wife, were suffering in their next rebirth.

It is the story of Mulian (目連) and his mother, however, that has become most popular among Chinese Buddhists as the rationale behind the rituals during the month of the hungry ghosts.

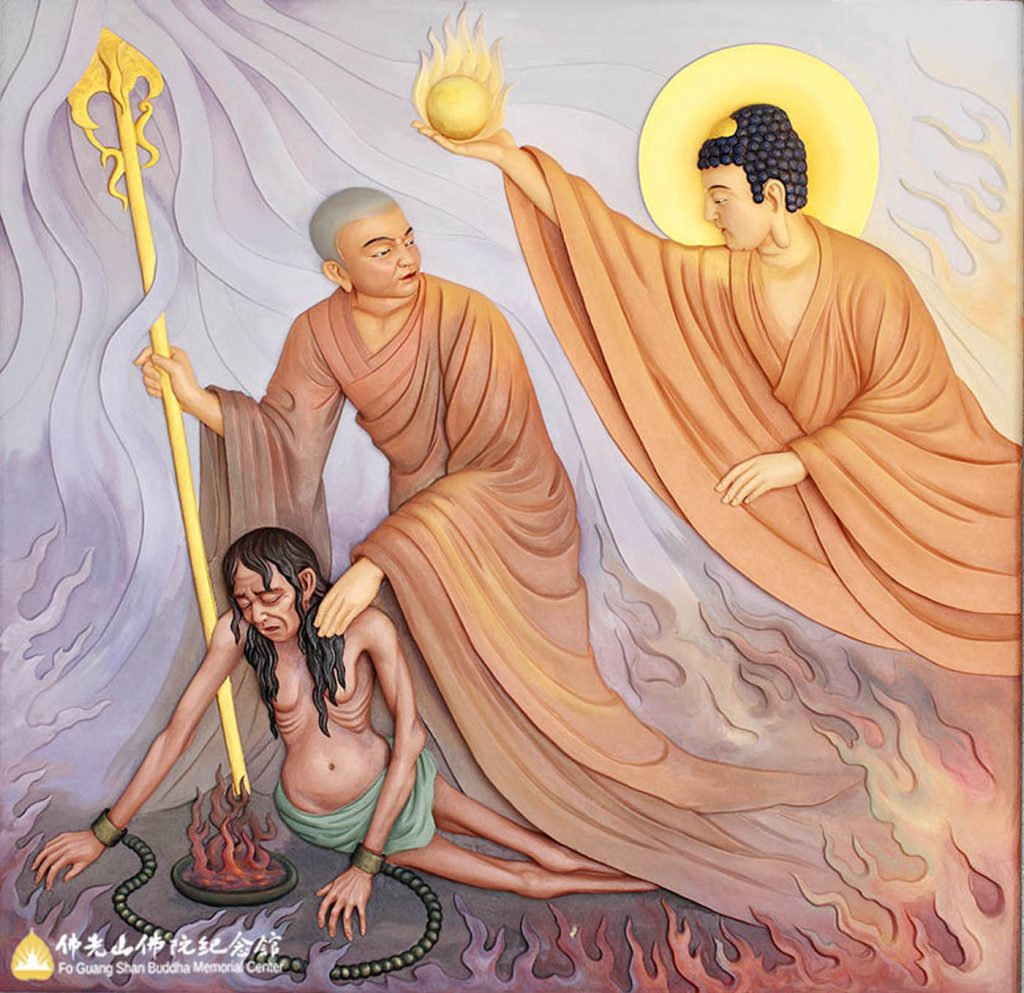

In the Yulanpen Sutra (盂蘭盆经), we find the story of Mulian, a disciple of the Buddha, who finds out that his own mother has been reborn in one of the hells as a hungry ghost and needs to be liberated.

He tries first to make a food offering to her, but she is unable to take the food because the food bursts into flames before entering her mouth, or other ghosts come to steal it.

Mulian then volunteers to take the place of his mother and endure the suffering for her, but this is not possible because each person has to suffer the consequences of his or her own past karma.

Mulian goes to the Buddha for help, and the Buddha teaches him how to obtain liberation for his mother. Through chanting and making offerings to the monks as they end their annual retreat on the 15th of the seventh month, Mulian is able to obtain liberation for his mother.

The annual prayers for the hungry ghosts can therefore transform them into proper ancestors who benefit from the merits assigned to them by their descendants through donations to the monks and offerings at the temple.

The story of Mulian combines the value of filial piety, a central value in Chinese culture, with Chinese Buddhist beliefs about rebirth and the rituals associated with it.

This is just one example of why Buddhism succeeded in becoming a Chinese religion.

Chinese people have a very practical mindset. In religious matters, this means that they see no problem with participating in the practices of different religions.

This tendency for syncretism is part of Chinese identity, and explains why Chinese Catholics in the Philippines continue to dutifully register the names of their beloved dead to be included in the chanting offered at Buddhist temples during the Yulanpen Festival on the 15th of the 7th lunar month.

At Seng Guan Temple in Manila, there are three days of chanting that culminate in the festival on the 15th of the seventh lunar month, which this year falls on Aug. 28.

For a few weeks prior to the festival, the temple sets up several counters so that people can come and make their donations in exchange for registering the names of their beloved dead. The same is practiced on a smaller scale in many other temples.

Various religions have different beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife.

Chinese Buddhism took some indigenous Chinese beliefs and developed them in a Buddhist context. The Taoists have their own appropriation of Chinese ideas about the soul and what must be done to help them.

Christians have a simpler framework for death. There is only one soul and there are no cycles of rebirth. At the moment of death, one’s choices throughout life result in a judgment that places the soul in heaven, hell, or purgatory.

The friends and loved ones of the deceased offer prayers and masses for them, to help them move closer to heaven or to ask them for their prayers if they are already in heaven.

If Christians, in particular Catholics, have their own way of looking after the dead, then why do Chinese Catholics still participate in the rituals of Buddhist, Taoist, or folk Chinese temples during the seventh lunar month?

Syncretism, or the attitude that sees no harm in multi-religious participation, is one reason; but I think it is also because Christianity has generally ignored the place of the seventh lunar month in the Chinese psyche.

Unlike Buddhism that took the millennia-old beliefs and gave them a Buddhist interpretation, Christianity ignored the beliefs and expected Chinese Christians to simply adhere to Christian beliefs.

Many Chinese Christians have embraced this with peace, preferring it to the complex systems of Chinese religions, but this is not the only way to respond to the environment of the Hungry Ghosts month.

There are no Chinese weddings and no blessings of houses or businesses during this month, so it is a lean time for Chinese parishes or Christian communities.

With creativity and innovation, special masses or novenas can be offered for the purpose of praying for the dead, thus giving Chinese Catholics an opportunity to express their devotion to the dead in a Catholic context.

I surmise that it is the absence of such services that drive Catholics to go to the temples frequented by their elders. There is a need being filled, a deep sentiment that needs to be expressed, and the faithful will go where this can be done.

There will always be Catholics who have a sigurista attitude to religion. They want to cover all the bases and make sure that they have exhausted all means to attain a goal such as care of the dead. There are those too who prefer a simpler path, a purer practice of one’s religion, and it will help them immensely if Catholic Churches develop their own ways of praying for the dead following Chinese timelines.