The new Batas Kasambahay or Domestic Workers Act (Republic Act 10361) is one of the hottest topics in households these days.

What has been an informal employment arrangement has been defined and given legal structure by lawmakers.

There is general agreement that protection for the nation’s estimated two million or more household helpers is necessary. Yet it has also raised anxieties and frustration among employers over the added cost and other obligations they face under the new law, and speculation the law may hurt the very people it seeks to help.

Intended to protect domestic workers from abusive household situations, the Batas Kasambahay imposes a set of obligations on employers, defining requirements for compensation and benefits, accommodations and meals, work safety, debts and repayment, and termination of employment. It also allows domestic helpers to join labor unions.

But there are indications the new law may backfire on the kasambahay.

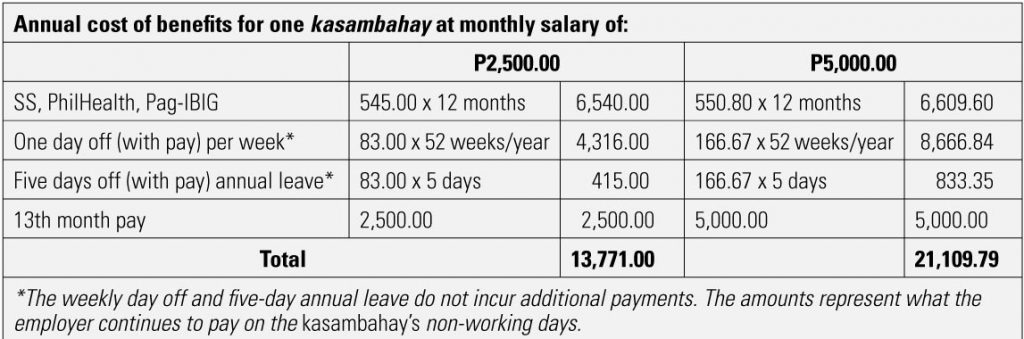

For instance, the law sets a minimum wage for helpers, requires 13th month payment, plus five days’ paid vacation after a year’s service.

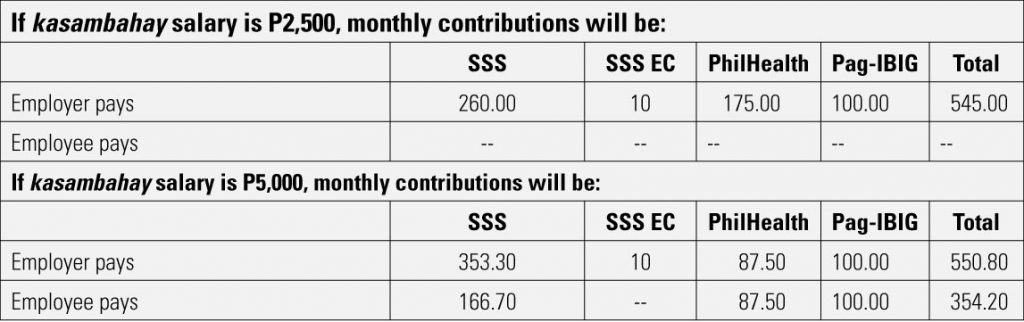

As well, employers must enroll their staff in the Social Security System, Philippine Health Insurance Corp., and the Home Development Mutual Fund, or Pag-IBIG. They must cover all monthly contributions – employers’ and employees’ shares – of any staffer who makes less than P5,000 monthly.

This adds to the costs of having helpers, and also entails more paperwork by employers as they register themselves and their staff with the government agencies, and then make monthly premium payments, fill out monthly and quarterly forms, and line up at the bank or government offices to submit the payments and forms.

“…by failing to see that the very decision to employ househelp is intricately linked with the wages paid to them, the Kasambahay Law threatens to increase the disincentive to hire among middle-income employers,” wrote J.C. Punongbayan, an economics graduate – summa cum laude – from the University of the Philippines, last February in social news network Rappler.

Indeed, the monthly contributions add up.

“I will not hire a kasambahay anymore. Okay na sa ’min na kami-kami na lang. Expensive magkaron ng yaya now,” Jocris Mangubat wrote to Topaz Mommy blogsite.

“This has been the reaction of people. Either they’ll not hire or they’ll (have fewer) kasambahays. That means less jobs for the poor,” Topaz Mommy blogger Frances Amper Sales – wife, mother and writer – responded.

The reaction supports Punongbayan’s speculation that casualties will happen in middle- and lower-income households as employers in this bracket lay off helpers to avoid the added expenses of supporting a minimum wage and new benefits.

For the same reason, employers may also hold off hiring young low-skilled workers who seek entry-level jobs as domestic workers, an unintended consequence of the new law, he noted.

These workers are usually migrants from the provinces who seek work in the city, and remit earnings home to help support the family. The disincentive to hire “robs them of the crucial first step they need to build their lives in the cities and bring their families… out of poverty,” he wrote.

For her part, Sales noted in her blog that employers may be more inclined to hire an applicant who already has memberships in SSS, PhilHealth and Pag-IBIG over someone who does not.

In reaction, various employers have expressed inclinations to change employment patterns, such as having laundry shops – not stay-in lavanderas – do their wash. Others are considering services of freelance part-time helpers.

Such options release the employer from legal obligations to a kasambahay.

Sales mused that the shift in service providers can create greater demand for other third parties, such as daycare centers and laundry shops, thus opening up more jobs in those sectors.

Meanwhile, the new requirements are turning off household employers.

When the new law was first in place, Sales said she had meant to consult a lawyer about it, but “… my household help stole money and gift certificates from me and ran off, so I didn’t need to anymore.” Since then, she has done without a helper, and reports her young family continues to thrive.

Aware that she will need one eventually when she returns to work outside the home, Sales expressed sentiments shared by many other employers over incurring higher costs for unsatisfactory service.

“I honestly don’t want to hire a yaya or maid anymore because of the Kasambahay Law. It’s not because I don’t think kasambahays shouldn’t have any rights. Even without that law, I’ve treated my household help so well. And what do I get in return? Theft, nasty gossip, petty fights, lies, laziness, greed, a sense of entitlement to what isn’t theirs, disrespect, poor treatment of my children… The list goes on.”

Sales, in other posts, reported catching an ex-yaya slapping her child, and another who stole.

“I’d rather not hire helpers anymore,” said another Topaz Mommy reader, identified only as [email protected]. “Paano naman ang iba na di ganun kalakihan ang sahod? We treat our kasambahay fairly… mas madami pa siyang oras ng tulog sa amin! I worked 7 a.m.- 5 p.m., I will go home, cook dinner while she watched the television. Oh di ba? after dinner manunuod pa siya ng TV dramas sa gabi. Sana magkaroon naman ng provision for the side of the employer.”

An anonymous writer to Topaz Mommy expressed similar sentiments, to which Sales replies “Yes. I also feel hindi protected ang employer.”

Meanwhile, at the workplace and in social gatherings, when household employers discuss compliance with the new law, responses include:

“Haaii! I just tell my husband he has to do it.”

“It’s giving me a headache.”

“Hindi na ako mag-maid.”

A recent report by Patricia R.P. Salvado Daway – “Questions about kasambahay law” – in the Philippine Daily Inquirer (July 14, 2013), suggests the law should be amended because it opens up new issues and fails to address others.

Changes should be guided by experiences encountered in its first year of implementation. Input should come from all stakeholders: employees, employers, and various go-vernment agencies including SSS, PhilHealth, Pag-IBIG, the departments of Labor and Employment, Social Welfare and Development, and Justice.

Notes one labor lawyer: while most employers will try to comply with the new law, a difficult and complicated law will hinder compliance. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 26, no. 4 (July 23-Aug. 5, 2013): 8-9.