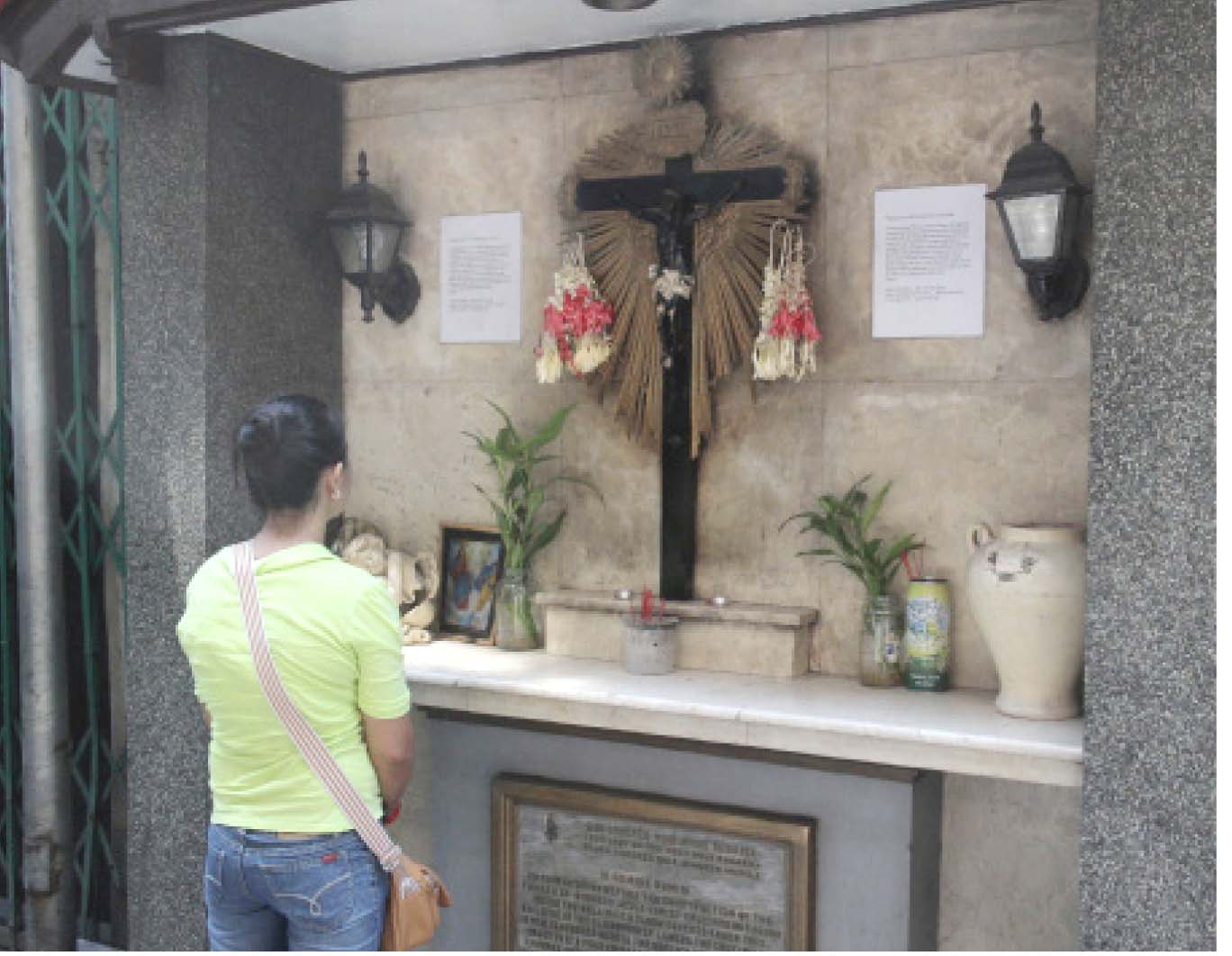

Blind faith. Almost all the people I asked and interviewed about the Sto. Cristo de Longos at Ongpin corner T. Pinpin streets did not know the provenance of the black cross, how it got to the place and what it represents. But, many remain devoted. Legends are recounted, heard from other devotees; some attribute answered prayers to the Cross, while others say they don’t care for the Cross’ history and that they find it meaningful to express their devotion to the Cross that symbolizes Jesus Christ’s sacrifices.

There are five shrines with the Cross icons in the greater Binondo area bound by San Nicolas, Binondo and Sta. Cruz. All of them are referred to as the Sto. Cristo de Longos by Filipinos and Tsinoys or Ko-lut Kong (戈律公 ko-lut for cross and kong for master or venerable) by the older Chinese.

- The original Cross in Binondo Church of the Holy Rosary (now known as Minor Basilica of St. Lorenzo Ruiz) is in a chapel beside the baptistry of the church;

- The Cross in a shrine at 516 San Nicolas St. (where the original Longos Church and the deep well where the Cross was retrieved is located);

- The shrine in a niche on the wall of Shoppers’ Mart (formerly Ongpin Supermart) on T. Pinpin cor. Ongpin streets, in Binondo;

- The Cross inside a shrine with a locked iron gate on T. Mapua St. near C.M. Recto Ave. in Sta. Cruz, Manila (CWC Building);

- The Holy Cross of Magdalena beside Metropolitan Hospital on G. Masangkay St.

The first two crosses (in Binondo Church and San Nicolas) have the figure of the crucified Christ on the Cross while the last three crosses (on T. Pinpin, T. Mapua and Masangkay streets) have only the Sagrado Corazon (Sacred Heart) on top of the Cross.

The first two are related since there was just one provenance. The third to fourth may also be related but the information is based on hearsay and needs validation. The fifth is not known as Sto. Cristo but the caretakers said it is related.

Devotees may not know the provenance of the black cross but have heard of miraculous cures, fulfilled supplications and answered prayers. Many churchgoers who attend mass at the Binondo Church make a point of walking to the corner, pass by the Cross, say a prayer or burn a candle even without making an offering.

The shrine where the Cross is displayed is a great leveler. Pedestrians from all walks of life, motorists in high-end cars, calesa, tricyle and jeepney drivers, vendors and kargadors, shoppers and bystanders can all pass by, make the sign of the Cross and utter a silent devotional prayer. Some do it merely out of habit but others do it out of faith.

Diane Lee is such a devotee – she asks for blessings in the mornings and pass by in the evenings for thanksgiving. The shrines all get offerings of flowers, fruits and incense and have prayers posted on the walls. They also have divination tablets (pua-pue 博杯 in Hokkien, 擲筊 in Mandarin), used in getting a yes or no answer on the spot.

Origins of the Holy Cross

Many have heard of the legend of the original Longos Cross now reposing in Binondo Church, which also appears in Internet searches like Wikipedia. It is said that the Sto. Cristo de Longos (Holy Cross of Longos) was supposedly the image of the crucified Jesus fished out from a deep well by a Chinese helper who was a deaf-mute. His speech was miraculously restored and he shouted with joy to proclaim the miracle.

As legend goes, the story has basis but the timing and the facts behind the true event may not be how it happened, according to people who now use the premises where the Cross was found and according to write-ups about the Ko-lut Kong in Chinese sources.

In “Venerable Hermandad del Santo Cristo de Longos: 308 Years of Labor of Love, Work of Faith and Steadfastness of Hope,” a paper presented by Wilson Sevilla Chua at the Manila Studies Conference and published in its MSA Journal (2013), recounted that in 1704 a deaf-mute accidentally fetched the effigy and subsequently brought the image to the Dominican priests at the San Gabriel Church in Binondo.

Sevilla Chua cited a narrative report of the Dominicans Orden de Predicadores (Order of Preachers) as his source but unfortunately, he did not give a citation on where or when this narrative of the Orden supposedly appeared. Repeated emails to him (from me and Dr. Bernardita Churchill) likewise failed to get a response. We needed clarification on whether the Cross retrieved from the well and the one reposited at the Binondo Church are one and the same. If the same, then the event occurred after World War II, not 1704.

We sent our query to Monsignor Josefino Ramirez, former rector of the Binondo Church and he in turn graciously sent his altar boy, Jayr Gernale, to bring my clarificatory questions to Father Gerard Francisco Timoner III, Prior Provincial of the Dominican Province, at the Sto. Domingo Church in Quezon City. We look forward to the response to shed light on this mystery.

Sevilla Chua writes:

In 1704 in the barrio of Longos near San Gabriel de Binondo a deaf-mute Sangley helper accidentally fetched the effigy of the crucified Jesus from a deep well. Miraculously, his speech was restored as he shouted to the people about what he found from the well. He brought the effigy to the chapel of San Gabriel Hospital and Chapel founded by the Dominicans in 1597 in Binondo. There, the Dominicans in-charge accepted and fitted the image with a cross and named it Santo Cristo de Longos.

Henceforth, people flocked to the chapel to venerate the Santo Cristo de Longos because of its countless miracles, increase of faith, and answered prayers. In 1848, due to the dissolution of the chapel of San Gabriel by the Dominicans Fathers, the image of Santo Cristo de Longos was transferred to Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary Parish in Binondo (formerly San Gabriel de Binondo).

In the course of time, due to the fame and miracle attributed to this Consecrated Cross of Longos, the Sangleyes and Mestizo de Sangleyes convert and parishioners alike organized a confraternity known as the of Hermandad were composed of twelve prominent and illustrious male members of Binondo.

Conflicting stories

The first paragraph was reprinted in the souvenir program of the Hermandad de Sto. Cristo de Longos published in 2012. The year 1704 appeared on the first sentence. However, it doesn’t seem plausible that the retrieval of the Cross from a well happened 300 years ago.

I asked the Binondo parishioners and they agreed that though the Cross was there at the church for a long time, they got to know about it only in modern times and not through stories of early immigrants.

Bernard Go, who headed the committee that printed the souvenir program, agreed that he too had doubts regarding the Cross’ antiquity. But he said he bowed to the wisdom of Sevilla Chua’s research output.

A search of the Chinese sources about the Sto. Cristo de Longos led me to an interview with the Chua family (not related to Sevilla Chua), who leased the property where the old Longos chapel stood (516 San Nicolas St., the building is bound by Sto. Cristo and Fundidor streets).

The couple, Manuel and Linda Chua, a second generation Chua family who had lived there since pre-war times, said that the Longos Church used to stand in nearby Sto. Cristo St., that’s why the street was renamed Sto. Cristo.

After the church closed down, a small chapel was maintained at San Nicolas St. The old Longos Church on Sto. Cristo St. must refer to the Our Lady of Purification, supposedly built in 1588 in Baybay, Longos, between Tondo and Manila.

Note that the old district of San Nicolas used to be called Longos. Baybay is San Fernando St. and Baybay Bridge was where the Sto. Cristo and Fundidor streets ended. Note that churches then and now are usually called after the name of the street and not its patron saint, i.e. Our Lady of Rosary now the Basilica of San Lorenzo Ruiz has always been known as Binondo Church, Our Lady of Buenviaje Church is known as Antipolo Church and so on.

The Chuas revealed that the Cross was retrieved from the well after the war and 1946 was their best recollection. The property where the old chapel stood was used by Mariano Guizon, Manuel Chua’s uncle, to raise pigs and goats. After the war, Guizon, the property owner, leased it to Choa Pee (蔡由坪), Manuel Chua’s father. It was when cleaning up the property for renovation that Choa’s Chinese carpenter found the Cross in the dried up well.

Not knowing what to do with the Cross, Choa asked the carpenter to bring it to the Binondo Church. Choa said the carpenter was from Fuzhou City, where the dialect, with distinctly nasal intonations, was dissimilar from the Minnan dialect spoken by majority of the Hokkien Chinese. The Binondo Church people could not understand him and because of his nasal intonation and loud grating voice, they concluded that he was a deaf-mute who could suddenly talk because of the Cross that he retrieved.

One thing is clear though, the Sto. Cristo de Longos from the well is now reposited in Binondo Church. “Henceforth, people flocked to the chapel to venerate the Sto. Cristo de Longos because of its countless miracles and answered prayers.”

If this passage from Sevilla Chua’s article refers to the Cross retrieved from the well, then this event happened in the post war era and not to the so called Sangleyes and Mestizo de Sangleyes of the 18th to 19th century.

But this does not discount the fact that the early Sangleyes and mestizo de Sangleyes of the 18th to 19th century did flock to the Longos Church, not due to the Cross but more to the fact that the church was built at the heart of Binondo for early Chinese immigrants.

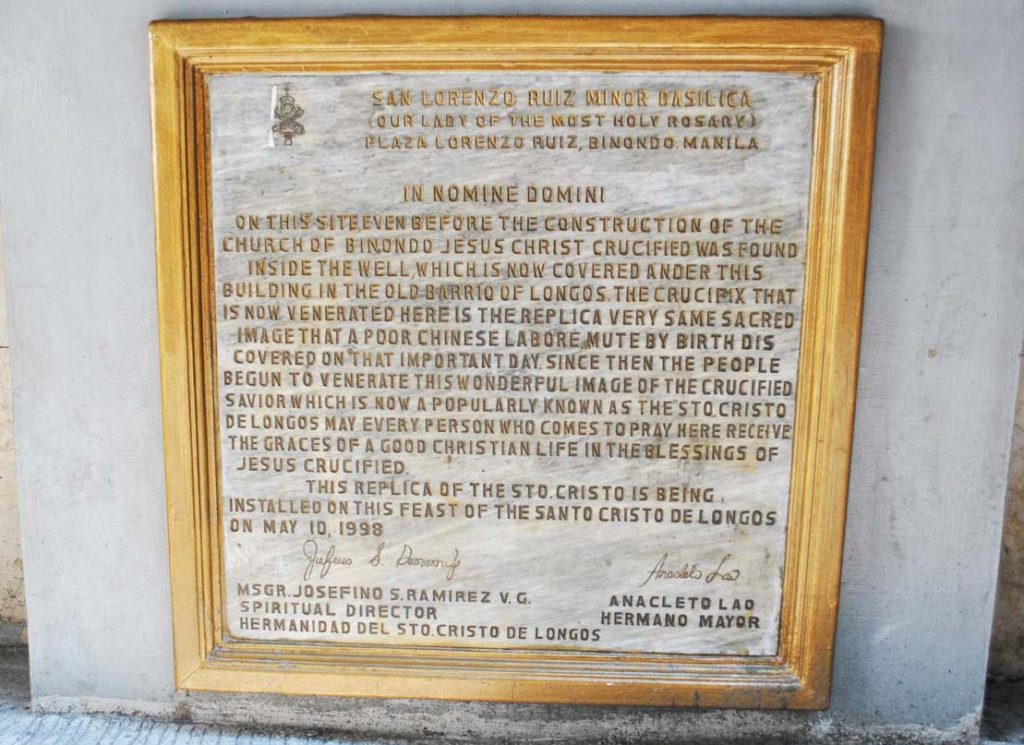

The well has since been abandoned and a small shrine was built at San Nicolas St. where the well was originally located.

Ramirez had a marker installed at the house to indicate that the original cross was retrieved from a well there. Devotees around the area who felt an affinity with the Cross offer sampaguita garlands and burn incense there.

Guizon, the property owner, refused to sell the leased property to the Chua family despite many offers. This was because when the Cross was found and given custody to Binondo Church, Guizon’s fortune had multiplied many fold and he attributes this good fortune to the Cross.

A replica with a shrine was built in its place. “Even if the original cross is no longer here and was brought to the Binondo Basilica, we are its true owners and it doesn’t need to be physically present to manifest its divinity and bring grace and blessings into our lives,” Linda Chua said.

They put sampaguita garlands, burn incense and a short prayer is pasted on the two sides of the Cross.

Sto. Cristo Shrine on Ongpin

The modern, elaborate shrine on the walls of Shoppers’ Mart on Ongpin St. was built in 1992.

A big fire hit Binondo in 1956. The entire Benavidez, Salazar and Nueva area was burned down. But it did not cross to T. Pinpin St. where an old wooden cross, much like the Sto. Cristo de Longos (and later also referred to as the Sto. Cristo de Longos) was nailed on the walls at the corner of Ongpin and T. Pinpin streets. Though no one could pinpoint when the wooden cross was put up, people agree that it was during Spanish times and that it was a demarcation marker that the area was administered by the Dominicans as against areas administered by Jesuits, Franciscans and other denominations.

An old Chinese gentleman (who wants to stay anonymous) told me that his parents said the two crosses at Ongpin cor T. Pinpin and at Misericordia are related. This could be true because the crosses both have the Sagrado Corazon (sacred heart) and not the crucifix images on them.

He said during the Spanish occupation, the crosses marked the entrance and the exit to the cemetery or burial grounds before they moved to the La Loma area. Burial grounds in many areas even now are beside the church. This information tidbit needs validation from the Manila records office if indeed there was a cemetery beside Binondo Church before.

The other wayside shrine in G. Masangkay St., according to its caretaker, is also related to these two crosses. Ongpin Street’s old name was Sacristia, Tomas Mapua’s was Misericordia, and G. Masangkay’s is Magdalena. The names may not be mere coincidence because Sacristia, Misericordia, and Magdalena do go together.

When the building where the Cross was located was torn down to give way to Ongpin Supermart in 1992, the Cross was put aside temporarily. Alex Ang, one of the building owners, reportedly got sick and made a promise to renovate the shrine for the Cross and take care of it throughout his life. He got well and fulfilled his promise.

The original Cross is now hidden inside a huge, shiny, brass cross and the spacious shrine used to be cleaned everyday by Betty Ching, now by Shoppers’ Mart (the former Ongpin Supermart). Today, both Chinese and non-Chinese stop by the shrine to light Chinese incense or offer flowers.

Other Sto. Cristo de Longos shrines

Tulay writer Baldwin Kho interviewed Ernani Bernardo Garcia, the son of 71-year- old Ernesto Balagtas Garcia, who was caretaker since 1967 of the Holy Cross of Magdalena on Masangkay St. (beside Metropolitan Hospital).

Ernani, an occupational therapist by profession, shared that in May, devotees would visit the chapel and offer trays of fresh eggs to the Holy Cross for answered prayers.

He said the three wayside crosses, in T. Pinpin, T. Mapua and Masangkay are related. He likewise said the elders in the community affirm that the Cross is 136 years old, it survived the war because the Magdalena area was not destroyed then.

This cross, like the one in T. Mapua St., has an alampay (shawl from shoulder to chest) that is lent to sick people for healing rituals. Other old alampay are cut into small pieces and distributed to sick people who request for them.

Kho elicited the information that it was in 1980, when the number of Tsinoys in Masangkay St. started to grow, they asked the Balagtas family who owned other statues in the shrine to allow them to burn incense as offering.

Since 1920, the Cross is brought out during the santacruzan (Catholic procession held in May celebrating the feast of the Cross) after three sets of nine-day novenas in honor of the Cross are completed.

The T. Mapua Cross, on the other hand, is brought out during the feast of the Black Nazarene in Quiapo in January.

Hermandad del Sto. Cristo de Longos

Sevilla Chua’s work on the Venerable Hermandad del Sto. Cristo de Longos, published in the Manila Studies Journal, is an important and significant work.

Sevilla Chua writes, “The Hermandad …is deemed to be the oldest and still existing organization in Binondo Church, as it celebrates its 310 years of indomitable faith and unwavering devotion to the service of the church and its parishioners.”

The Constitution of the Hermandad, dated 1904, found in the archives of archdiocese of Manila, said in its preamble that the Hermandad was founded 200 years ago (1704-2014). However, while the Hermandad is now a fraternity of devotees to the Holy Cross, the earlier Constitution of the Hermandad found in the archives may possibly not refer to the Cross found in the well but to the Longos Church itself in San Nicolas.

In fact, if indeed this Longos Church is the church of Our Lady of Holy Purificacion (1588), then it is the second oldest church in the Philippines, next to the original San Gabriel Church in Intramuros, Manila (which later became the Binondo Church, now the Basilica of Lorenzo Ruiz).

Hermandad members’ vows are addressed to the Cross: “To see in your cross the length to which your love will go, that you did love us so much that you kept nothing back; To see in the Cross the horror of sin, and to depart forever from it; and To see in the Cross the wonder of your love and to surrender forever to it.”

Further research needs to be done to determine when these vows were adopted.

Manifestations of syncretism

The Sto. Cristo de Longos is one of the examples of the unique syncretism in religious practices and traditions of the Filipinos and their fellow Tsinoys. It is the Catholic black cross but Tsinoy devotees offer incense, sometimes food, and even burn paper money and consult divination tablets on top of offering candles and garlands of Sampaguita flowers.

It is interesting to note that the Sto. Cristo de Longos is another icon connected to a well. The other cross found in the well, the Virgen del Pozo, back of the in Sta. Ana Church, is the Virgin of the Well (see Tulay July 5-18, 2011 issue). Both are worshipped by Tsinoys in a mixture of Catholic and Chinese rites like incense burning.

Indeed, as Fr. Aristotle C. Dy and I concluded in our paper on “Syncretism as Religious Identity: Chinese Religious Culture in the Philippines,” when Catholicism practiced by Filipinos meets Chinese religion practiced by Chinese Filipinos, the result is always an interesting and colorful amalgam of rites, rituals and beliefs. (Email Tulay Fortnightly if you can provide more information on this story. — with inputs from Baldwin Kho). — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 27, no. 4 (July 22-August 4, 2014): 8-11.