Catarman Tsinoys join hands to save one of Samar’s last Chinese-language schools.

In most Tsinoy communities in rural areas, Chinese-language schools are the focal centers of community involvement. Supporting the school creates a bond among residents who trust the school not just to prepare their children to become successful individuals but also to pass on the Tsinoy heritage to the next generation.

The continued existence of their Chinese-language schools fulfills an educational goal for their children and is closely linked to the Tsinoy community’s existence.

Indeed, it was this love for, and hope, in education that drove the founding generation of Chinese in Catarman, Northern Samar, to build 加膽曼華僑小學 Catarman (Chinese) Chamber Elementary School.

It was named after the Catarman Chinese Chamber of Commerce, an association of Tsinoy businessmen in Catarman and nearby San Jose, Bobon and Mondragon towns.

Of the six Chinese language schools in Samar island, only two remain: CCES and Catbalogan Community School, in Western Samar. But seven decades after its founding, changing demographics and other realities have brought CCES to its knees. Neglected, in debt and falling apart, it was saved from closure by alumni who just would not let it go.

A campaign through social network site Facebook in 2011 awakened the bayanihan spirit of alumni and other members of the local Tsinoy community. This in turn led to the creation of the CCES Foundation, Inc.

Best school in town

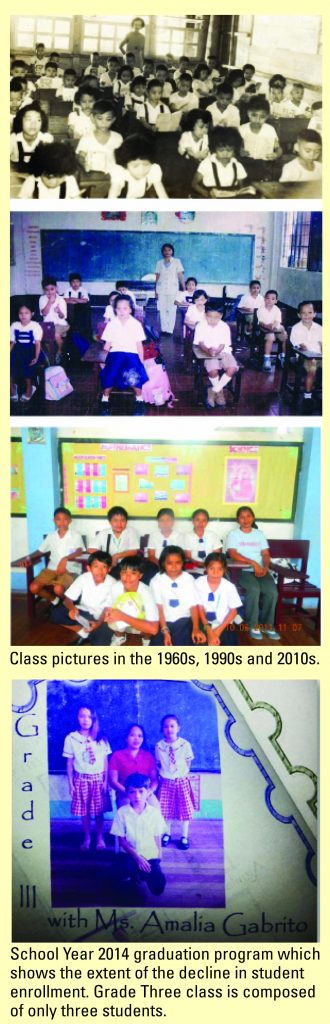

In its heyday, CCES was considered the top elementary school in Northern Samar. Norbert Lingling Uy, alumnus from Batch 1969, notes that “CCES was then the only school in Catarman that offered Chinese education, and English education was handled by very dedicated and qualified faculty staff.”

Jocelyn So-Roman, Batch ‘84, moved to CCES from public school in third grade. At first reluctant and fearful, she was eventually glad of the move.

At CCES, “the learning process and concepts were a bit more advanced than in public schools,” she said. “The formation and learning ethics had much more impact; CCES is conducive to a convenient and comfortable learning environment. And of course, learning Chinese was an edge.”

The CCES also had the only marching band during town fiestas in the 1960s and 1970s. Its basketball court was the first in Catarman and provided a venue for the town’s basketball tournaments. Its theatrical plays entertained the townsfolk. This small-town elementary school produced exemplary graduates who excelled in different fields including legal, social development, medicine, and business.

Alumni today include a past president of the Philippine Heart Association, a university dean and Papal awardee Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice, top notchers in licensing exams for lawyers and certified public accountants, prominent business people and consultants, a former Catarman mayor and an incumbent vice mayor.

Collective endeavor rooted in the past

The school was a product of the Tsinoy community’s cooperative endeavor and the main focus of the Chinese chamber’s activities. The 100 or so chamber members – from wealthy families and their Tsinoy employees to small sari-sari store owners and peddlers – contributed either cash or goods.

Community elder Vicente Ortiz said, “Everyone contributed. The amount of contribution differed but… each one gave his or her share.”

Money raised went to pay teachers’ salaries, lodging and food (some of the teachers were recruited from Bicol and Manila), operational expenses, and repairs. Others gave teaching and school supplies, students’ uniforms, band equipment, petroleum gas for lighting, students’ snacks, even boxes of matchsticks.

The generosity practically gave every student a free education.

Benito “Lim-meh” Lim, my uncle, worked for a Chinese employer in the 1950s and remains a big supporter of the school. “I’m always (respectful) to those Chinese pioneers who established the school (which provided) free tuition to all students for nothing. All my children benefited,” he said.

In his own special blend of Hokkien, Spanish, Waray and Tagalog, he adds:“Iyong ang otang aten sa escuelahan (that is what I owe to the school).”

An amazing and perhaps vital part of this fundraising process was Alejandro Chan Sr., dubbed the “collector.” Chan was the first known collector of the community. He inspected cargo as it arrived and left Catarman port. His son, Alejandro Jr.,

Origins: obscured but not forgotten

Founded in 1938, Catarman (Chinese) Chamber Elementary School is Catarman’s oldest existing private school, and perhaps in Northern Samar. The origins of its founding is obscured through time. Only the year embedded in its school logo remains. The founding date cannot be verified, but is traditionally celebrated on Oct. 10, also known as Shuang Shi Jie (雙十節 Double Ten), Nationalist China’s foundation day.

The school operated continuously except during the Japanese Occupation (1942-1945). The earliest memories of the school’s existence in the years after World War II were collected from recent interviews of surviving elders of the Chinese community.

Right after the war, the Ministry of Education re-opened schools. There was an influx of thousands of students who had four years of disrupted schooling. Some had already grown up.

The Ministry asked for volunteer teachers. Anyone who finished at least elementary school could teach elementary students.

Oliva Chan-Delorino, a teenager at the time, was one such volunteer. The daughter of the leader of Catarman’s Chinese community, she recalled being relieved of teaching a year later because her father was a Chinese national. She went to teach at CCES, becoming one of the school’s first teachers after the war.

In 1947, CCES only had 15 students. All the students were in one class with no level segregation. Only two teachers taught students of different ages in the same room. There was no principal.

Jose Bolos, a Chinese migrant from Guangdong province, taught Chinese subjects in the morning; Chan-Delorino taught English subjects in the afternoon. Later, another teacher from the government-run Catarman Pilot Elementary School joined the two. Like Chan-Delorino, she lost her post because her father was Chinese.

The student population was small. This is because the rural Chinese sent their children to China for schooling. In China, the children learned the Chinese language and were immersed in the culture.

With rampant poverty, particularly in the rural villages, it was hoped that by being there, the children would also learn the values of hard work and diligence.

Before 1949, the Chinese in Catarman sent children to China with only one adult parent as a companion. Six children, ages six to 14 from the Chan, Ching, Sy and Uy families, went to Fujian.

Around six more from the Cantonese Chan and Cho families went to Guangdong province.

Then in 1949, China was plunged into a bitter civil war and eventually taken over by the communists. Its borders were closed. Two of the 12 children sent to China were trapped there, unable to return to their families in the Philippines until decades after.

With this, the Chinese in Catarman could no longer send their children to China nor visit ancestral hometowns. Thus, the student population at CCES rose to more than 60 students from only 15.

helped list down the amount of goods and their owners. Apparently, this list was used to determine how much a chamber member would donate to the school: an unofficial, informal school tax.

The first known school building right after the war was a nipa hut at the center of the business district. Later, it rented space on the second floor of a large house nearby.

In 1946, Chan (Sy) Sing Liat, a Chinese from Catbalogan who moved to Catarman during the war, became head of the Chinese Chamber and led the Tsinoy community in buying land for the school. On it was a large wooden two-storey house which was converted into the school building.

As student population grew, another two-storey building was built in 1964, almost entirely of concrete, next to the old structure. It was the first concrete private school building in Catarman. Donations collected by Chamber members from business partners and suppliers in Manila and Cebu paid for it.

Other structures followed, including a canteen, covered court, and playground.

There was even a fire truck to service the rest of the town since Catarman’s local government did not have one.

Decline and perseverance

The school’s lone fire truck could not stop the great Catarman fire on March 1, 1965.

Half the old school burned down, as did the entire business district which made up about half of the poblacion.

My mother Nimfa Chan-de la Cruz recalls that afterwards, Chinese business owners walked about looking dazed and bewildered, their clothes and faces dirty with ash and mud. Some Chinese, having lost their businesses, returned to China.

This had little impact on the school at first. But when these people left, it was the first of many social changes that contributed to the school’s decline, and that of other Chinese-language schools throughout the province.

The CCES was previously called Philippine Northern Samar Chinese Elementary School and at one time had both the old and new names inscribed in one school logo.

Today, the word “Chinese” has been dropped.

It was mandated by the Department of Education, Culture and Sports in 1976 to comply with new rules to bring Chinese schools under its jurisdiction and fully integrate them and their students into mainstream Philippine society.

Chinese schools previously governed by Taiwan came under full jurisdiction of the DECS. The flags, of Taiwan and pictures of Chiang Kai-Shek, which used to adorn classrooms in Chinese schools, were removed.

Meanwhile, rising teacher salaries and benefits in the public school system proved too much for CCES. Many good teachers left for public schools. Some students transferred to the schools where these teachers went. Enrollment dropped, as did funds for teacher’s salaries. A vicious cycle began.

The school could no longer make ends meet with just tuition income.

Helda Lim-Gallano, CCES Chinese language teacher and school supervisor, went house-to-house to solicit donations to keep the school going, cover operational expenses and payroll.

It has not been easy.

Business in Northern Samar, particularly in Catarman, declined when demand for copra and Manila hemp, its main industries, fell. As well, the town’s river silted up, becoming impassable for batel (small ships from Bicol and Cebu), which used to enter the river and dock on its banks. Financial support for the school dwindled drastically when almost all its first-generation Chinese immigrant founders died.

Meanwhile, there was little support from the second generation who had migrated to the cities. Assimilated into local society, many lacked interest in their Chinese heritage.

A hundred or so sponsors used to give generously. Today, there are 12 people and businesses, and only some of them give regularly.

Lim-Gallano perseveres in her teaching and fund raising.

“I like to impart my little knowledge in Chinese language (and) serve my alma mater. I enjoy baktas (walk) for the exercise although there are times that I feel ashamed (of asking for donations), but I put it in mind that what I am doing is for the benefit of the school,” she writes.

With the school running a huge deficit each year, some of Catarman’s Tsinoy families wanted the school closed and its lot divided amongst them.

But the remaining few elders and the majority of the community fought the idea.

The lot and the school was paid for through donations of more than 100 Tsinoy supporters.

Such a place cannot be divided among a few individuals, especially one so dear to so many. For many, the school holds childhood memories and the memories of their parents; the collective memory of the entire community was at stake.

Long-time school administrator Fe Angley-Adriatico, who often used personal funds to cover the school’s deficits, said she persisted despite many challenges because “I want to continue the legacy of my father.”

For Chinese elder Lim, “It’s human nature: some are willing to give, some are not. We should not disappoint our pioneer Chinese to let the school fall at our hands [and] during our generation.”

In 2012, the school’s permit expired and the Tsinoy community pondered whether to close it down.

Facebook group

In 2011, Lucille Paredes Lee and Jocelyn So-Roman, both CCES graduates of 1984, visited the school and saw its sorry state: poor enrollment, a burgeoning deficit and many unlicensed teachers. The building was falling apart: restrooms had no toilet bowls, windows were broken, the roof leaked, there was no library, no clinic, no principal’s office, no faculty room. Worse, there was no school principal, and no records of past students and teachers.

The two used Facebook to publicize the school’s current state. Membership grew quickly to more than 400 alumni in the country and abroad.

Enter the foundation

Alumni met to discuss the school’s problems. The CCES Foundation Inc. was born.

Its goal: revive the school.

Descendants of founding elders and prominent Tsinoy families of Catarman have climbed aboard. Heading the group is Bayani Tan.

“Our parents would turn in their graves if we keep the school in its sorry state… it’s the legacy of our parents that we have to keep alive,” Tan says.

With the help of Tsinoy community leader Teresita Ang See, Tan met board members of the Federation of Filipino-Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Inc. in February. The board urged the foundation to encourage the re-establishment of the Catarman Chinese Chamber and bring in new migrant Chinese business owners.

The Federation would solicit and course assistance from its own membership through the local chamber.

75th founding anniversary

In August 2012, alumni held their homecoming with special focus on saving CCES. In 2013, alumni and former teachers met in Catarman, and once in Manila to mark the school’s 75th anniversary and remarkable survival.

By then repairs were being done, enrollment climbing, the school’s permit renewed. The library was revived with donations; lists of past students and teachers were recreated through Facebook contribution and oral interviews.

The CCES Alumni Association was registered on the Securities and Exchange Commission. And finally, the Yi Bai Bao En (一百報恩) fund-raising project was launched.

Yi Bai Bao En meant “100 returns of gratitude” or “Usaka gatos nga pagbalos” in Samar’s Waray dialect. This project encourages alumni and others to donate time, money and ideas to help the school.

The event also revived the dormant Catarman Chinese Chamber of Commerce.

New Chinese immigrants doing businesses in Catarman became members and officers. Their participation enabled them to be involved in community service and support the school.

Yi Bai Bao En

Yi Bai Bao En, the flagship program conceptualized by alumni and CCES foundation member, Norberto Lingling Uy, was launched during the school’s 75th-anniversary celebrations.

The CCES Alumni Association Inc. is a vital mover for the school’s revitalization. The association falls under the umbrella of CCES Foundation Inc.

Many alumni collectively lent strong hands as Catarman’s Chinese Chamber works to restore the school.

Despite a rocky road, the CCES lasted because of exemplary support from past elders of the Catarman Tsinoy community. This is now being emulated by the succeeding generation through the foundation and alumni association.

There is good reason to keep CCES going, not just because its alumni are fond of it.

It is a vehicle through which Tsinoys will continue to learn about their roots.

It will be unfortunate if the next generation forgets its Chinese roots as the school decays. It is most untimely to give up one’s Chineseness just when China has risen from the ashes after years of poverty and suffering to become a world power.

In the midst face of territorial disputes with China, learning this, especially the language and culture of our forefathers, will help promote friendlier relations and greater cooperation between the Philippines and China.

Armed with an understanding of our cultural heritage, flourishing under the Philippine sun, Tsinoys are uniquely suited to acting as the bridge of tolerance, respect and understanding. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 27, nos. 1-2 (June 17-July 7, 2014): 14-17.