Ateneo de Manila University Press recently came out with A Visit to Manila and Its Environs, an English translation of a Dutch book by Jacob Adolf Bruno Wiselius published in 1876.

Wiselius, a controller with the Dutch colonial administration in Java, visited Manila and neighboring Laguna province in 1875.

He had prepared well for his visit, having read most of the recent books on the Philippines by Spanish, French and English authors. His job in the colonial administration in Batavia (now Jakarta) also gave him access to information on the way Spain was managing its colony in East Asia.

Wiselius wanted to know what the Dutch could learn from Spanish practices.

The publisher, Ateneo de Manila University Press, pointed out: “Accounts from non-Spanish sources that focus on the way the Philippines was ruled in the final decades of the Spanish colonial era are rare, and this travelogue is a valuable addition to our knowledge of that period.”

Just like most works on the twilight decades of the Spanish colonial era that inevitably contain references to Chinese in the Philippines, Wiselius’ 100-page travelogue devotes one section to the Chinese.

The section “The Chinese” takes up less than two pages, and may not yield much new information on the Chinese in the Philippines that we are unfamiliar with.

But it is a rare account from Dutch sources. Told from the perspective of a foreigner, especially a Dutch colonial administrator of Java colony in Southeast Asia that also had a sizable Chinese population, Wiselius’ observations on the Chinese in Manila and its environs are worth reading.

They contribute to our knowledge and understanding on the Chinese in the Philippines. Below is the full text of Wiselius’ “The Chinese:”

There are many Chinese living among the natives in Manila, but far fewer in the interior. Like their colonial masters, the Catholic natives view them as pariahs and heathens.

One only has to look at the history of the Chinese in the Philippines and at their legal position to realize that the way they are treated here is much worse than in our archipelago.

The government doesn’t give them any support and in case of a conflict between a native and a Chinese, the native can be sure to be vindicated. Even the killing of a Chinese (not a rare event) is punished with only three years of exile, since it concerns a pagan.

The real cause of the hatred toward the Chinese is their greater industriousness, persistence, and frugality, which are in sharp contrast with the inborn apathy of the natives. He can only quietly do his trade if he converts to Catholicism.

Most of them in the interior have followed this route and marry a Christian native woman, but they are then not allowed to work on Sundays and feast days, at least not in public. (In the city of Manila it is only on Sundays they are not allowed to work.)

However, it takes more than persuasion by a European missionary or friar to make a Chinese give up the belief of his ancestors. Even if he embraces another belief with all its rituals, it is merely a cover to enable him to do his business.

The missionaries may claim a number of conversions, the truth is that a Chinese, despite all efforts, remains a Chinese whether in Manila or China (where in an emergency he allows himself to be baptized by a European for one dollar).

Despite being married to native women, children of several generations retain the customs and characteristics of the father.

We know this very well from the Chinese in our archipelago, and those in Manila are no different.

According to Gaspar de St. Augustin in his description of the Philippines, the native prefers to receive a real from a Chinese to a dollar from a Spaniard. So why should anyone be surprised about the prosperity of the Chinese.

Those who are familiar with our archipelago know that the native here thinks in the same way, but still feels the same contempt for the Chinese as his Philippine fellow tribesman.

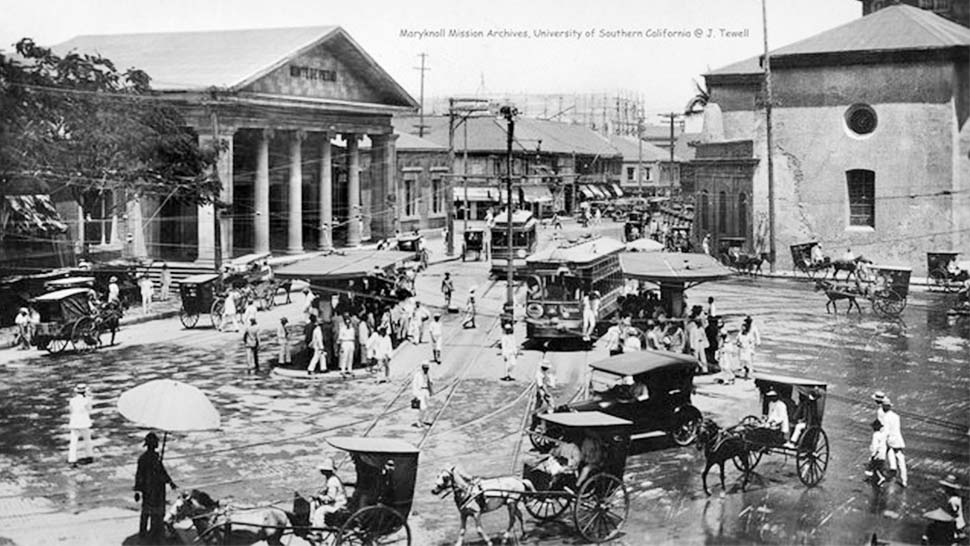

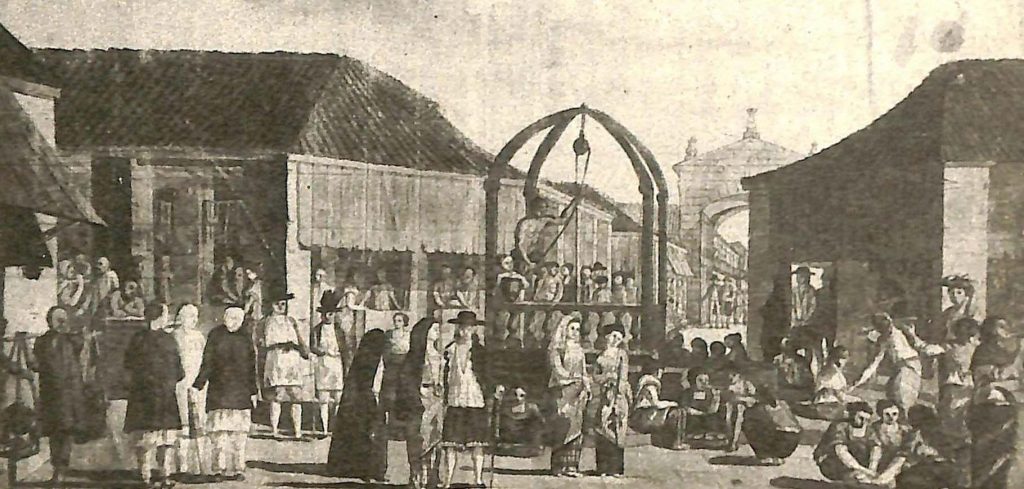

The Chinese in Manila are usually referred to with the derogatory Sangley, that is traveling merchant and the hatred of the Spanish and natives for the enterprising spirit of these born merchants reached such levels that at one time there was general slaughter, while on several other occasions they were expelled.

A major grievance against them was that they sent their savings to China. This still happens with silver and as a result this metal is often very scarce.

However, after every banishment or brutal punishment the government became conciliatory again because, as one said, the colony cannot survive without the Chinese.

As other Europeans started to settle in Manila, the harsh treatment was softened and one tried through heavy taxation to curtail their influence and progress.

This doesn’t scare the Chinese and the fact is, here as elsewhere, that wherever he has gained foothold, despite all obstacles put in his way, all trade and especially the retail trade will be captured by him, and natives and Europeans pushed out.

The taxes paid by the Chinese in the Philippines are very considerable. They are targeted by the tax collector and much dissatisfaction is often the result. They are obliged to maintain their accounts in Spanish.

Despite the continuous migration of Chinese men to Manila, there are very few Chinese women among them. This necessitates marriages with Chinese mestizos and native women.

They live as they do on Java and are occupied with trading. They follow their ancestral customs and do not get involved in matters that are not of their concern. They commit very few crimes that fall under the penal code.

Whenever there are in a place a sufficient number of Chinese to have their own leader, the government can authorize them to elect principalia from among them with similar responsibilities to those on Java. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 13 (December 06-19, 2016): 5-6.