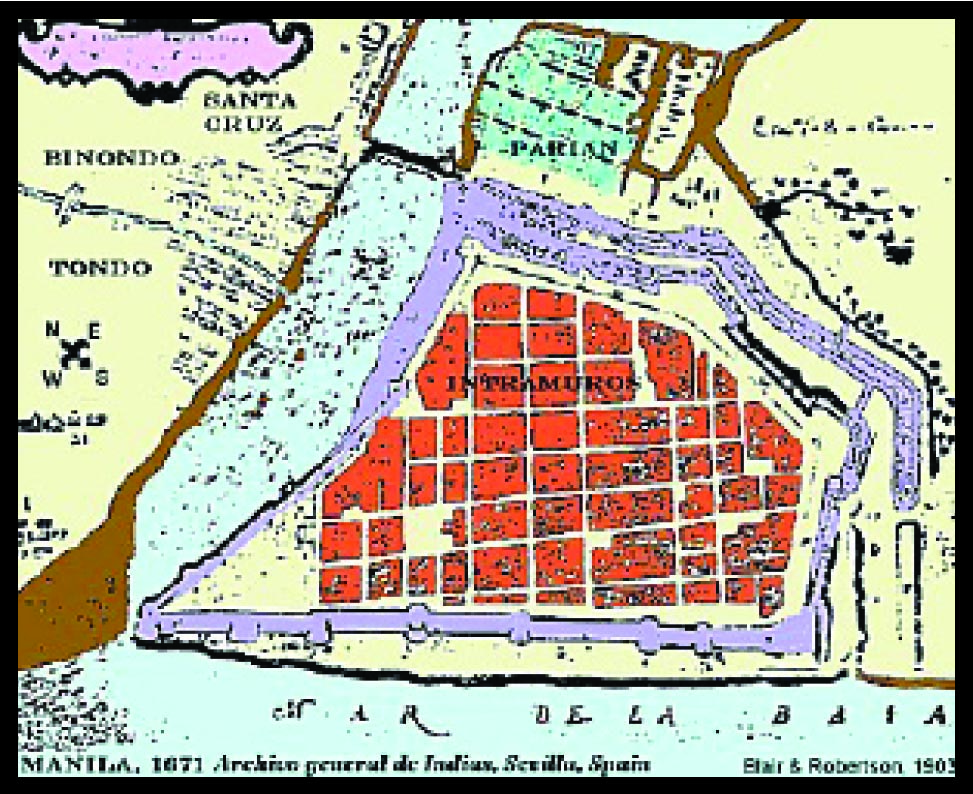

In 1580, the Mexicans expelled the Chinese to outside the walls – Extramuros – at a spot along the Pasig River, “within sight and cannon shot of Intramuros” and where they would localize the great silk market called Parian. Thus, Parian became the name of Manila’s Chinatown. As Manila was an extension of Mexico in the Americas, it can also be considered the first American Chinatown.

Except for Manileños, not a lot of people are aware that Americas’ first Chinatown was established in Manila.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus missed his goal of reaching the Indies and “discovered” America instead. Spain laid claim to America, and by 1535, created the viceroyalty of New Spain, Mexico. Two Iberian explorer/navigators quickly followed suit: Vasco da Gama reached India by sea in 1497, and the Ferdinand Magellan/Sebastian del Cano expedition circumnavigated the globe from 1519-1522.

From Sevilla, they crossed the Atlantic, rounded the tip of South America (Straits of Magellan), crossed the Pacific, and stopped in Cebu island where Magellan was killed. Elcano pushed on through the Indian Ocean and reached Spain in 1522.

Blessed by the Pope and his imaginary Tordesillas Line (1494), Spain colonized North America in 1521. In 1564, after dispatching several exploratory voyages from Mexico to Asia, the Spanish Crown delegated Miguel Lopez de Legazpi to sail across the Pacific from Acapulco, Mexico, and take Cebu island.

Having spent 34 years in Mexico, Legazpi took a contingent of other Mexicans with him, among them the Augustinian monk and brilliant navigator Andres de Urdaneta. He also brought American silver with him to do business with China.

In 1565, from Cebu, Urdaneta followed the trade winds and accomplished the first roundtrip voyage of the Pacific, in the process launching the Manila Galleon trade that endured for 250 years, until 1821.

One galleon ship per year made the round trip across the Pacific. In some years, there were as many as three galleons.

Galleons carried primarily silk of all kinds and porcelain from China, but also other luxury goods from many other places in Asia and the Indian Ocean world.

In 1571, Legazpi built Manila as capital of the archipelago’s newly named Las Islas de Filipinas (in honor of Emperor Felipe II). Manila was established as an outpost of America administered under Nueva España (Mexico) and not a free-standing colony of the Spanish empire.

The Chinese in Manila

When Legazpi arrived in Cebu and then Manila, he immediately met Chinese, about 150 of them at first, who had been coming in their junks (fan chuan 帆船) from Fujian province to trade with the natives throughout Southeast Asia.

These early traders were mainly Hokkien-speaking Minnan people of southern Fujian, hailing from Xiamen, Quanzhou and Changzhou, known already to medieval Western travelers as Amoy, Zaitun and Chincheo.

The locals on Cebu and Luzon islands called these Hokkien people “sangley” – apparently from Hokkien siong lay (changlai 常來 “coming frequently”), which aptly described the sojourner or frequent visitor, but not permanent settler.

From the original 150 or so junk traders, the Hokkien population grew rapidly, as more and more junks sailed to meet the Mexicans in Manila, attracted by the silver coins and ingots mined in Mexico and Peru, which they brought from America.

Silver was in great demand in China, as the country was transitioning from paper currency to silver.

In exchange for American silver, Chinese traders eagerly supplied the merchandize for the galleon ships, beginning with the one that Urdaneta captained in 1565 on his first return voyage across the Pacific.

Americas’ first Chinatown

Throughout the 250-year-old global trade, silk from China remained the single largest trade item, followed by porcelain or ceramics, and many other beautiful things like Manton de Manila, not just from China, but from all over the Indian Ocean and Nanyang. Manila hemp used for the sturdy ropes that held the sails of the ships was also in great demand.

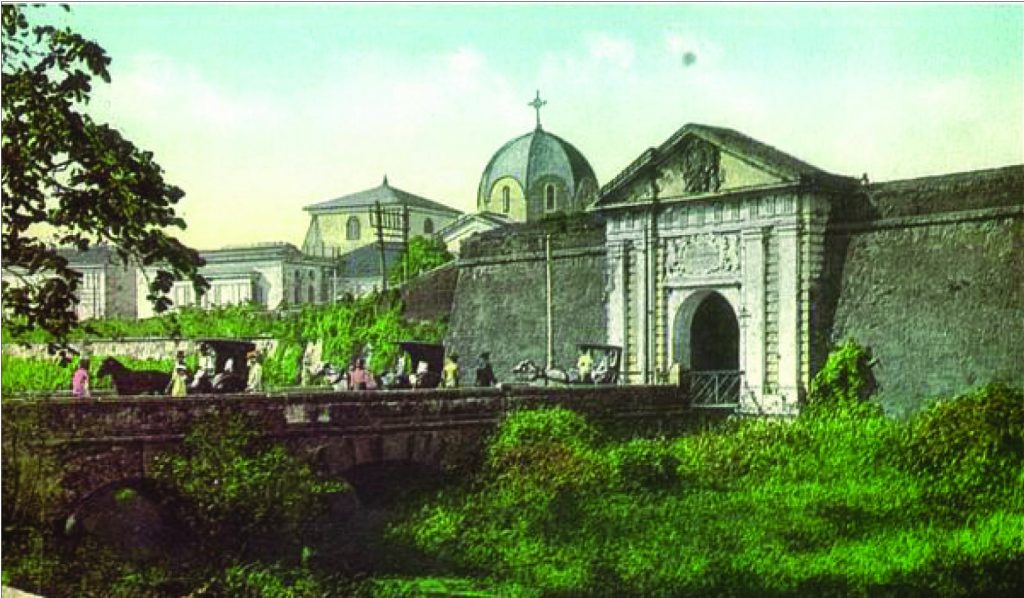

While Mexicans built their own residences inside the city walls, Intramuros, they grew nervous as the number of Chinese rose around them.

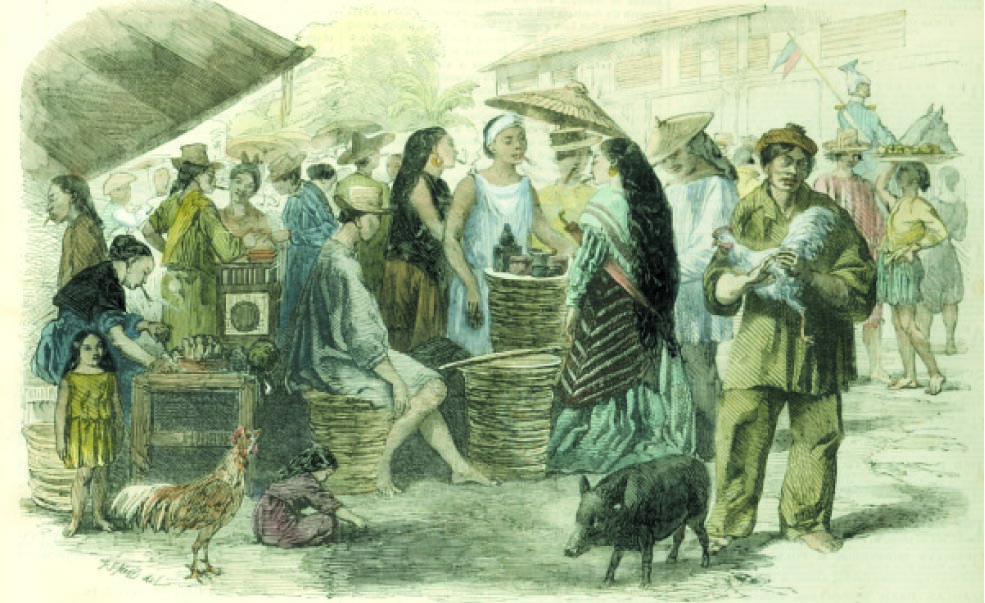

In 1580, they expelled the Chinese to outside the city walls, Extramuros, at a spot along the Pasig River, “within sight and canon shot of Intramuros,”and where they would localize the great silk market called Parian.

Thus, Parian became the name of Manila’s Chinatown, and as Manila was an extension of Mexico in the Americas, it can also be considered the first American Chinatown.

Before long, the Chinese made themselves indispensable to the Spanish long distance trade as well as to the daily life of the small community established to be an entrepot – a link or bridge – to trade with China.

By then, China had prohibited foreigners from setting foot on the mainland.

As early as 1574, just three years after Manila was founded, the sangley lived scattered among Mexicans in Intramuros.

The Spanish governor noted the continuous flow of Chinese who supplied the colony with the many articles used in daily life, such as bread, sugar, wheat and barley flour, nuts, raisins, pears and oranges, silks, wine, porcelain and iron, and other small things, which were lacking before the Chinese arrived.

The Chinese population in Manila quickly swelled from 150 in 1564 to some 10,000 by 1586. After 10 years, it rose to 25,000 and then 30,000 by the end of the century. Eighty-five percent were Hokkien from southern Fujian, others from Guangdong, also junk traders from their cosmopolitan port city of Canton.

The newcomers quickly outgrew the planned capacity of the Parian, making it densely packed.

Meanwhile, the Mexican and European population in Manila Intramuros grew to no more than 500 over the first decade, which consisted of a skeletal crew of priests and missionaries; soldiers and officers; government officials; merchants and businessmen.

Many of the traders began to settle permanently in the Parian, where they lived and opened their shops, paying high rent to the Spanish authorities, and paying high taxes on their businesses, eventually to disastrous consequences.

Many of the Hokkien who came to Manila decided to stay indefinitely or permanently, building homes and shops, while raising families in the Parian, because they responded to Spanish demands for goods and services beyond the galleon trade.

It can be captured by this description of Judge Antonio de Morga, about the items Chinese brought to Manila which had nothing to do with the luxury trade:

…metal basins, copper kettles and other copper and cast-iron pots; quantities of all sorts of nails, sheet-iron, tin and saltpeter and gunpowder. …wheat flour…preserves made of orange, peach, pear; nutmeg and ginger, and other fruits of China; salt port and other salt meats; live fowls of good breed and many fine capons; quantities of fresh fruits and oranges of all kinds, excellent chestnuts, walnuts and chicueyes (both green and dried, a delicious fruit); quantities of fine threads of all kinds, needles and knick-knacks; little boxes and writing bases; beds, tables, chairs and gilded benches, painted in many figures and patterns. …domesticated buffaloes that resemble swans, horses, some mules and asses; even caged birds, some of which talk while others sing, and they make them play innumerable tricks. The Chinese furnish numberless other gewgaws and ornaments of little value and worth, which are esteemed among the Spaniards…

In truth, he admitted, “without these sangleys, the city would not be able to survive and sustain itself, because they are the master of all crafts, hardworking people, and charge reasonable prices.” From merchants and traders, the Chinese established enterprises to provide the colony’s diverse needs.

Chinese artisans and enterprises

Without competition from either Mexicans or Spaniards, or from native Filipinos, historian Edgar Wickberg noted: “Spanish settlements with needed goods and services was an open field for Chinese enterprises.”

Because so many of the enterprises consisted of providing daily services and everyday goods, they were located on site in the Parian, which Mexicans frequented on a daily basis.

Instead of continuing to transport many of these manufactured items from China, Hokkien artisans and workers followed in the wake of the merchants, relocated themselves and their families, their workshops and retail businesses in the Parian.

The in-migration of these artisans and workers was one of the key factors leading to the Chinese population explosion as well as the growing occupational diversity in the Parian. Father Domingo de Salazar, first bishop of Manila, made this point clearly:

These articles have already begun to be manufactured here, as quickly and with better finish than in China; and this is due to the intercourse between Chinese and Spaniards, which has enabled the former to perfect themselves in things which they were not wont to produce in China.

In this Parian are to be found workmen of all trades and handicrafts of a nation, and many of them in each occupation.

They make much prettier articles than are made in España, and sometimes so cheap that I am ashamed to mention it.

They are so skillful and clever that, as soon as they see any object made by a Spanish workman, they reproduce it with exactness.

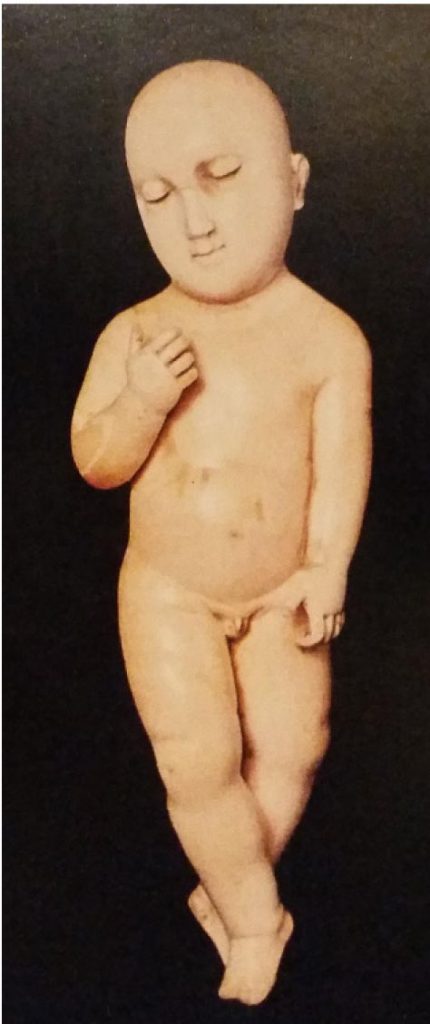

Not to be outdone, other Chinese artisans already adept at working with ivory – a material not known in the Americas – quickly adjusted to Spanish demands for religious figures, as De Salazar also noted with appreciation and admiration:

I think that nothing more perfect could be produced than some of their marble statues of the Child Jesus which I have seen. This opinion is affirmed by all who have seen them. The churches are beginning to be furnished with the images which the Sangleys make, and which we greatly lacked before; and considering the ability displayed by these people in reproducing the images which come from España, I believe that soon we shall not even miss those made in Flanders. What I say of the painters applies also to embroiderers, who are already producing excellent embroidered works, and are continually improving in that art.

These artisans also produced Spanish-style chairs, leather bridles and stirrups in such good quality and so cheaply “that some merchants wanted to load a large cargo of these articles for Mexico.”

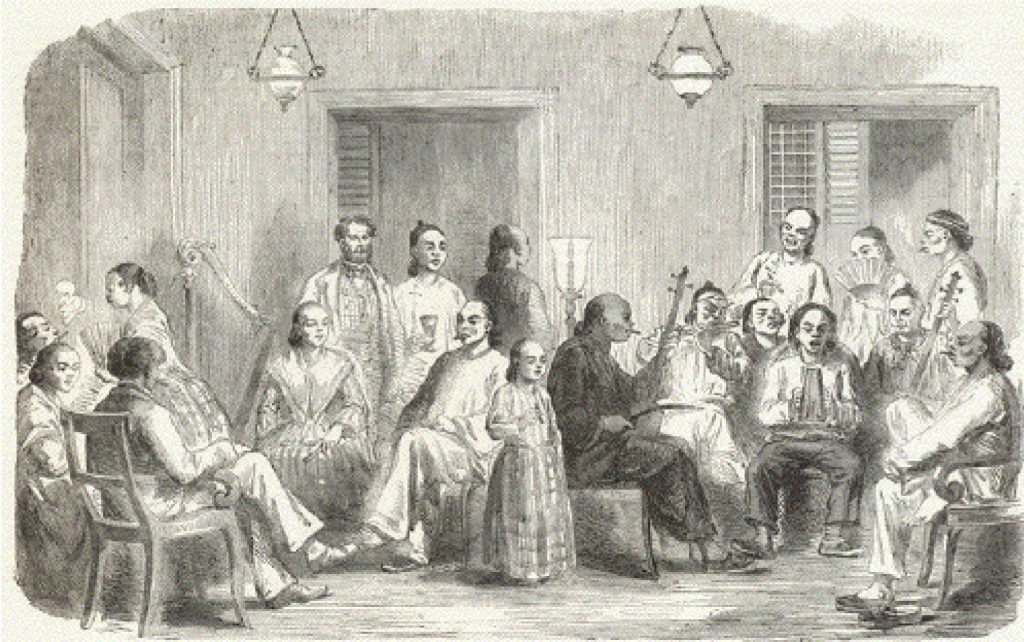

Equally telling were the different services that the Chinese in the Parian provided for local consumption, for themselves and for the Spanish community.

De Salazar noted that Chinese market gardeners produced vegetables in plots all over the city, those peculiarly Chinese as well as Spanish and Mexican favorites, “their tables [in Manila] as well provisioned as in Madrid and Salamanca.”

In 1590, he made businesses in the Parian that Mexicans and other foreigners patronized, including herbal doctors and apothecaries; eating houses; bakeries that sold wheat bread; homebuilders of European-style stone houses.

The eminent Wang Gungwu has concluded that Manila “was the first truly large Chinese community overseas and easily the largest one in the sixteenth century.”

Discord and distrust

But all was not well in Manila. What appeared to have been a mutually beneficial and interdependent relationship between Spaniards and sangleys in Manila also sowed the seeds of discord and distrust that led to incidences of extreme violence.

Even as some Spaniards praised the Chinese for their skilled labor, commercial spirit, and overall alacrity in meeting every Spanish need and demand, these same Mexicans sought to control and discipline Chinese entrepreneurship with high rent in the Parian, and a series of improvised taxes, tariffs and licensing fees that the Chinese viewed as onerous, arbitrary and unfair.

Meanwhile, Spanish officialdom was getting nervous about the rapidly rising numbers of Chinese, most of whom resisted conversion to the Catholic religion.

Mincing no words, the ever present and observant Antonio de Morga explained it this way: “From this, a lot of trouble arises, because with so many infidels there could be little security in the land; they are bad and vicious people.”

The fear that Morga embodied turned violent in 1603, when Chinese numbers in Manila grew to as high as 30,000.

Adding to Spanish anxiety, the Dutch forced their way into Manila, which already had to deal with unwanted Portuguese traders.

When the Chinese staged a protest against the heavy and arbitrary taxes and fees imposed on them, especially when repeatedly assessed even after paying up, the Spanish authorities unleashed the full force of their military might against the protestors.

The reported massacre of 25,000 Chinese practically decimated the Parian. Those who escaped death were deported back to China. Manila came to a standstill.

Before long, the Mexicans in Manila beckoned Chinese to return, which they promptly did and repopulated the Parian, resuming life and business as before, supplying the galleons with luxury merchandize while provisioning the resident Spanish population with food, clothing, shoes and all other necessities of everyday life.

Just as the Chinese re-inserted themselves into the Spanish American colony, protests against heavy taxes and fees in 1639 and again in 1662 and 1668 provoked Spanish reprisals on the Chinese with the same heavy, violent hand, each time followed by destruction and desertion of the Parian.

And each time, after a brief respite, traders, artisans, laborers, families from Fujian and Guangdong would return to the site of their bloody confrontation with Spaniards, who in turn enabled a revived and rebuilt community to rise from the smoldering ashes of death to grow and thrive again until the next state campaign to cut them down.

Spanish historian Manel Olle sums up this unresolved tension well: “Manila would have been an absolutely unviable city without the presence of Chinese residents and traders, but at the same time, [Spaniards] hated the Chinese, feared them and denigrated them…”

There was simply no easy way out for the Mexicans/Spaniards, who could not rid themselves permanently of the Chinese community.

The Chinese constituted the backbone of the Spanish mercantile colonial enterprise in Manila. Total dependence on the Chinese trumps Spanish fear and mistrust, hence, their haste to recall the Chinese to Manila shortly after each periodic outburst of “ethnic cleansing,” setting the stage for the interplay between integration and rejection that characterized relationships in the first American Chinatown. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 10 (October 18-31, 2016): 8-10.