In Taal, Batangas, the origins of a Catholic devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, known as the Virgin of Caysasay, can be traced back to a statue of a woman of Chinese appearance recovered from the sea, which local Catholics venerated as the Virgin Mary.

It is highly probable that the statue was one of Mazu 媽祖, the Chinese goddess of the sea and patron of seafarers, but for centuries was venerated as the Virgin Mary. Mazu herself has two temples dedicated to her in the Philippines, in La Union and in Batangas, with plans currently underway to build a new temple in Manila.

It is fascinating to note that local devotees have conflated the two female deities, stressing that they are “emanations” or “manifestations” of each other, to the extent that an annual festival is held when the two images are venerated together, with both Chinese and Catholic rites.

In Sta. Ana, Manila, the parish church is dedicated to the Virgen de los Desamparados (Our Lady of the Abandoned), but on a side street across the church, there is a century-old Chinese temple dedicated to Sta. Ana Lao Ma 仙鬥撈媽 (Mother of Sta. Ana or Ma Cho Po or Mazupo 媽祖婆 of Sta. Ana), which enshrines an image of the Virgin Mary under the latter title.

The image in the shrine is considered the same as the Lady of the Abandoned because early Chinese immigrants felt strongly that they were abandoned children who left their homes to seek better livelihoods to support loved ones back in their Chinese hometowns. Devotees regard her as a manifestation of Guanyin (觀音) and Mazu.

These examples highlight the Chinese propensity to combine religious practices and devotions, even deities. While this practice is common in Chinese religions, its expansion in the Philippines to include Catholic devotions is unique.

Chinese religion

Chinese religion is a broader concept than a syncretism of Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism. Until the 1950s, Chinese religion was traditionally defined as the integration of these three teachings (sanjiao 三教), but scholars have since acknowledged the limitations of this approach.

The worship of heavenly bodies and powers in the natural world, divination, exorcism, and the proper care of ancestors and ghosts, for example, were practiced in China long before these three traditions appeared on the scene.

In ancient China, there was already an understanding of metaphysical forces that affect human life in practical ways.

Key characteristics of Chinese religion include a hierarchy of gods, ghosts, and ancestors based on the imperial bureaucracy in China.

This hierarchy of worship objects, with their corresponding ritual practices, was expanded and enriched by the Buddhist and Daoist deities that came later, demonstrating the fluidity of Chinese religion, which is the product of syncretic processes.

In time, Confucian principles became the rationale for maintaining order and observing moral codes of conduct.

It is safe to say that Chinese religion cannot be limited to the overlapping aspects of the three religions of China, despite their similarities and diversities.

The fourth element of ancient Chinese religion is conventionally called popular or folk religion, because before religious specialists came along, ordinary Chinese people had their own ways of honoring the dead and relating to the universe, through a loose mixture of beliefs and practices.

In contrast to popular practice is elite text-based practice that came with the institutionalization of religion.

These two levels of practices have been described as “Great and Little,” “elite and peasant” and “official and popular.” Predictably, elite practice tends to be more defined while popular practice is very fluid and accommodates syncretism very liberally.

For example, Chinese Buddhism absorbed Guangong (關公), a general from the Eastern Han Dynasty who is immortalized in the classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms and later deified in folk religion. He was given the Buddhist persona of Qielan Bodhisattva (伽藍菩薩).

Guanyin, the female deity who hears the world’s cries for help, is a bodhisattva in Chinese Buddhism and the goddess of mercy in Daoism and popular religion. In a singular sense, Chinese religion is a broad category while in a plural sense, Chinese religions can refer to any or all of the three traditions or popular and folk religion.

In the Philippines, Chinese religion exists at all levels. Throughout the country, especially in the major cities, there are folk temples dedicated to various deities, as well as established Buddhist or Daoist temples. There are no Confucian temples, but ancestors are venerated in private homes, cemeteries and special halls located in large temples.

Syncretism among Chinese Filipinos

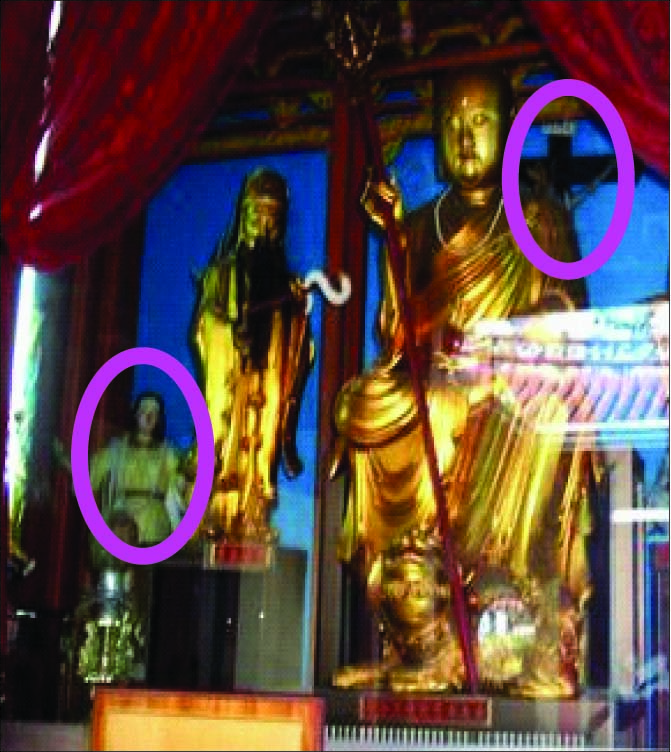

The syncretic practices that can be observed in the Philippines come in different forms. First is the striking and unique Chinese-Filipino practice of displaying and worshipping religious images from different faiths side by side.

Chong Hock Tong (崇福堂 Chongfu Tang) is a folk temple inside the Chinese Cemetery, and its main altar houses the image of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, known in Hokkien as Te Tsong Ong (地藏王), the god of the underworld and the focus of prayers for the dead. Statues of Chinese and Catholic deities surround his image.

The “Ecumenical Church Simbahan ng Santo Singkong (大千寺)” in Tondo, Manila, founded by the geomancer, So Chiaoyee (蘇超夷), is dedicated to universal religion. It is mainly devoted to two folk Chinese deities, but the temple also enshrines images from different faiths, such as Catholic, Muslim, Buddhist, Daoist, Hindu, and even a depiction of Saturn!

So’s universal religion preaches that all gods are the same under heaven, whether they are called “God the Father,” “Yahweh,” “Allah,” or “Tiangong 天公.”

The practice of worshipping deities from different faiths, mainly Buddhist, Daoist, and Catholic in the case of the Philippines, on the same altar is repeated in many home altars of ethnic Chinese people, where Guanyin and the Virgin Mary often stand side by side.

A second form of syncretism is the use of Chinese rituals to worship non-Chinese deities.

In his classic work, The Chinese in Philippine Life 1850-1898, Edgar Wickberg describes the procession of Our Lady of La Naval in Manila being accompanied by Chinese musicians and fireworks, and river barges shaped like pagodas honor St. Nicholas, believed to be the protector of the Chinese.

In Camarines Norte, Southern Luzon, there is an image of Jesus known as the Jesus Nazareno of Capalonga, which is worshipped in grand Chinese style. Chinese worshippers burn incense and paper money, make food offerings, and use divination sticks to venerate this Black Nazarene.

A third form of syncretism is the identification of Chinese deities with Catholic ones, as previously shown by the example of Mary and Mazu.

Among men, devotion to Guangong is very popular, as evidenced by the many temples dedicated to him, especially in Manila and Cebu. An interesting fact is that Guangong has been associated with Saint James (Santiago in Spanish) as a protector of the Chinese.

Both are perceived as heroes in their respective historical eras, which explains their spiritual role as protectors.

Understanding syncretism

In my previous examples, I have broadly defined syncretism as the simultaneous practice of elements from different religious traditions. But how do we make sense of such practices?

It is widely known that most Chinese people have a practical attitude towards religion and naturally combine popular religious beliefs with elements of established Chinese religions. In the Philippines, this syncretism included popular Catholicism, as evidenced by the stated examples.

This is important to remember when considering the syncretic religious practice of many Chinese Catholics.

There is a “syncretic amity” when figures such as Jesus and the Virgin Mary are found side by side with Guanyin, Guangong and Ksitigarbha, and there is still the awareness of multiple sources. The iconography alone highlights the fact that the images come from different traditions, as Guanyin looks Chinese or East Asian and Mary’s features are those of a sharp-nosed Westerner.

There is no assimilation, subordination or synthesis evident here, only the friendly coexistence of deities in the same place of worship.

The second form of syncretism I described earlier is the worship of Catholic deities using Chinese ritual styles, as in the case of the Jesus Nazareno of Capalonga. It is still clearly a Catholic devotion, but the use of Chinese ritual forms makes it an example of symbolic encompassment.

Elements from Chinese religion have a subordinate symbolic role and can be said to have been assimilated into Catholic practice. From a Catholic perspective, this is an example of liturgical inculturation.

There is also a third form of syncretism, which is the identification of Chinese deities with Catholic ones. There are several examples of the Virgin Mary being conflated with Mazu or Guanyin.

Conflating goddesses is not uncommon in Chinese religion, but there is more than syncretic amity at play here. The deities are not simply being placed side by side. In the minds of devotees they are the same, and yet the statues remain distinct.

There is no assimilation or symbolic encompassment. In the future, there may be subordination or dissolution if devotees can understand that the two images are actually distinct, and they can confine their devotion to only one of them.

This, however, is unlikely to happen because of the syncretic mindset and the reluctance of authorities to prohibit the practice and correct ways of thinking, despite their discomfort with the situation.

In the syncretic process, the conflation of deities must be left open-ended. Synthesis may never be reached, so this form of syncretism will continue.

The pragmatism of Chinese-Filipinos extends to their religious practices. They may officially belong to a Christian church, but their actual religious practices incorporate elements from different religious traditions.

Syncretism is a hallmark of Chinese religion. The Philippines is unique because this syncretism has been expanded to include Catholicism, without inventing another religion or sect.

This unique brand of syncretism has become part of the Chinese-Filipino identity.

The syncretic nature of Chinese religion is not the only reason why Chinese people feel free to express their spirituality in diverse ways. Pluralism in Filipino society and the harmonious blending of eastern and western influences in its culture created an ideal environment for ethnic Chinese people to adapt their customs and traditions.

While it is something that is taken for granted, the expansion of Chinese religious culture in the Philippines to include Catholic elements is what makes the Chinese in the Philippines unique.

This practice reveals a cultural mindset that is key to understanding whether one is deeply engaged with Chinese culture.