A person I regret never meeting was photographer John K. Chua (蔡傑安), widely regarded as a leading local advertising photographer. His works have appeared in advertisements for Mitsubishi, Audi, Lexus and Mountain Dew. It was John and his company, ADPhoto, that pioneered the use of digital photography in the local advertising industry.

John was also known for his big heart, and he would use his photographic talents as a platform for his advocacy, such as special children and animal rights.

But one advocacy that had a special place in John’s heart is Banaue and its people.

His passion is evident in his photo exhibition of Banaue held at the third-floor art gallery of the Fo Guang Shan Mabuhay Temple.

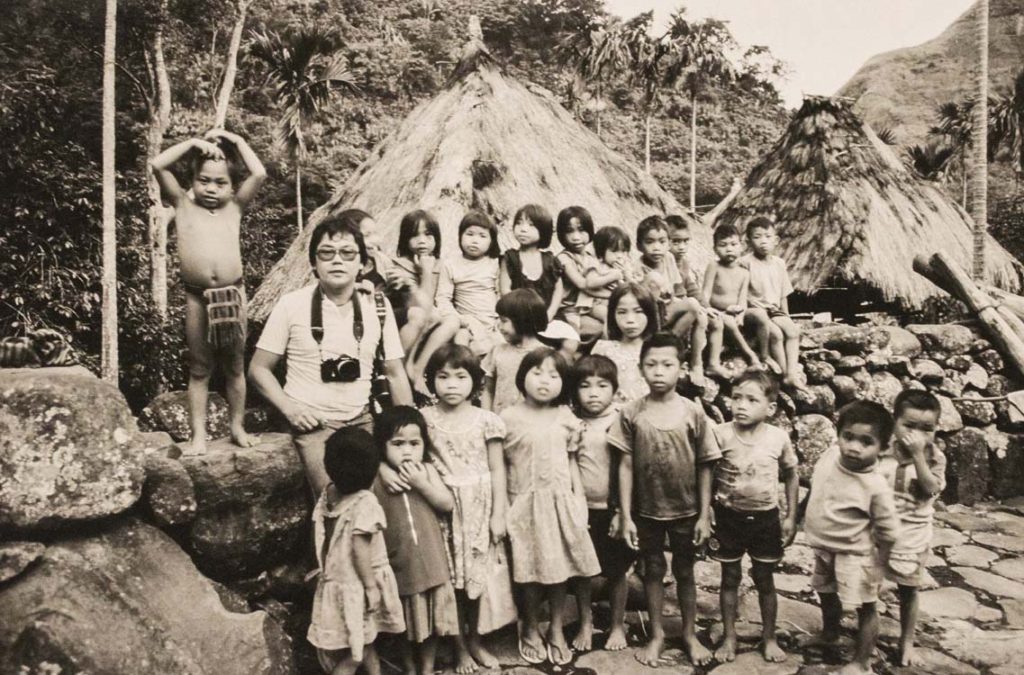

The exhibition focuses on photographs of Banaue John took between 1970 and 2015. The photographs reminded me of the works of Eduardo Masferre, who took documentary photos of the lives of the Igorot people between the 1930s and 1950s.

Both men immersed themselves deeply into their respective communities, and their subjects seemed comfortable enough to reveal who they truly were to the cameras.

However, in my opinion, the subjects in John’s photos seemed more at ease, and his photos seem to express more emotional content.

His set of photographs of an Ifugao funeral, featuring a portrait of a deceased man seated on a chair surrounded by his family members, illustrates this.

The photo did not look macabre, because John captured the moment of intimacy between family members and the deceased.

Aside from taking photographs of their everyday lives, John also amazingly captured the grandeur of Banaue and its environs.

One photo shows a rice paddy field taken from above, with its brown muddy water lit by the sun transforming it into pools of gold. I always thought John took these shots using a drone, but during an exhibition, his widow, Harvey Chua, claimed otherwise.

She also shared that before the use of drones became common, John would hire a helicopter and fly over Banaue to take aerial shots.

It is evident from his photos that John loved Banaue. One of the major panels at the exhibition revealed that John first traveled to Banaue upon the advice of a travel writer back in the 1970s. That writer was none other than Harvey herself.

Despite being soft-spoken and gentle, Harvey proved very capable of managing their business affairs, which enabled John to concentrate and flourish as a photographer.

Their working relationship seemed to define the word “partnership.”

Harvey said, in jest, that when she and John would give talks on the business aspect of photography, John would start by saying, “Hi, I am John and I am passionate about photography.” Then she would say, “Hi, I am Harvey and I am passionate about John.”

Indeed, John had many reasons to be grateful to Banaue and its people, who were the subject of his first photo exhibition back in October 1978, which turned out to be more of a cultural event than a photo exhibition, as it included lectures and daily performances of traditional dance.

The Intercontinental Hotel where the event was held even featured an Ifugao hut that had been disassembled and transported all the way to Makati. It was then reassembled inside the hotel’s ballroom, as the showpiece of the exhibition.

While the current exhibition is much simpler, its organizers decided to bring back one highlight of the 1978 exhibition, whose opening featured an Ifugao, Mongit Panpanhon, cutting the ceremonial ribbon of the event using his bolo. Mongit has since passed away, so his son, Milado, was given the honor of cutting the ribbon of the new exhibition with a bolo.

John did not just take photos of the Ifugaos – he also gave back to the community. During one visit in 2011, he noticed that the walls of the rice terraces in the town of Batad were deteriorating. When he asked the local community why nothing was being done, their response was they were waiting for government funds, to which John replied, “But your ancestors built the terraces without tools or funds! In fact, no government existed then!”

So, John began an online campaign to raise awareness of the issue and a call for action, resulting in donations of tools, such as rakes and hoes, as well as volunteers from local mountain areas and other provinces around the country. The volunteers were eager to participate in the reconstruction and organized an advocacy group, which they named, “Bachang,” the Ifugao term for “Bayanihan.”

John’s call for action also resulted in media attention, which raised the issue a national level, leading the government to release funds for the construction of a new concrete road to Batad which improved the lives of local people.

Asked why a temple was chosen as the exhibition’s venue, Harvey explained that when she was teaching the business of photography at De La Salle College of St. Benilde, she was approached by a student whose parents were devotees at the Fo Guang Shan Mabuhay Temple.

She and John were then invited by the temple in 2017 to attend a Chinese brush painting exhibit at its gallery. By then, John was suffering from colon cancer, but he still went to the exhibit, on a wheelchair. The gallery subsequently invited them to mount their own exhibitions there.

However, it was not until after John passed away in 2018 that his first exhibition on special children was hosted by the temple.

John was a man with a big heart. When Harvey was asked if she knew where John’s passion came from, she then shared an interesting story about John when he was 16 years old.

After a violent argument with his mother, John left the country for Bangkok with just the clothes on his back and some spare change. Upon arriving in Thailand, he was able to find shelter in a warehouse space that doubled as a backpacker inn. But in order to stay legally in the country, he had to travel to neighboring countries, such as Laos and Myanmar every so often to get his passport re-stamped before returning to Bangkok.

To survive, John had to rely on his wits and did odd jobs, such as washing cars, and to keep his mind active, he would read books and magazines left behind by other travelers.

A year after arriving in Thailand, the owner of the warehouse told John that he reminded him of a butterfly that was eager to fly but whose wings were not yet developed.

By then, John realized that it was a sign for him to return to Manila and reconcile with his family, so he phoned his brother, and his mother wired him money for his plane ticket. Harvey said living on the streets of Bangkok enabled him to appreciate what he had and share them with those who had less.

Even in death, John’s big heart is still beating for the people of Banaue. While his photographs featured in the exhibition are not for sale, a coffee table book with photos of Banaue taken by John is available for sale.

Sales of the book, A Banaue Story: Restoring a World Heritage Site, will help raise funds for the restoration of the walls of rice terraces in Banaue and nearby areas.

For book orders, email: [email protected] or log on to http://www.banauerestoration.org or call 709-5001. “Falling in Love with Banaue and Beyond” exhibit, organized by the Fo Guang Shan Mabuhay Temple in partnership with the Fo Guang Yuan Manila Art Gallery, will run until Dec. 1. The Fo Guang Yuan Manila Art Gallery is located at 656 P. Ocampo Street, Malate Manila and is open from Tuesdays to Sundays, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.