Chinese devotees consider at least three images of the Virgin Mary in the Philippines as Christian emanations of the Chinese sea goddess Mazu.

Aside from the Virgin of Caysasay, there is also Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage in Antipolo (Virgen de la Paz y Buen Viaje) and Our Lady of the Abandoned (Virgen de los Desamparados) in Santa Ana, Manila.

All three are also linked with the element of “sacred water.”

The shrine of the Virgin of Caysasay is famous for its miraculous spring. That of Antipolo used to boast of a baño de la Virgen (Virgin’s bath at the foot of a small waterfall) and that of Sta. Ana is associated with Virgen del Pozo (Virgin of the Well).

The image in Antipolo, while associated with Mazu, has no separate shrine that is Chinese in character, but became popular among the Chinese. Like Mazu, the Virgin of Antipolo protects travelers. As to the image in Sta. Ana, recent studies have shed more light on its origins.

Beyond the syncretism of combining Catholicism and Daoism, the Sta. Ana Church is even more fascinating and unique. The main icon of Sta. Ana Church is the Virgen de los Desamparados (Our Lady of the Abandoned), also known as Virgen del Pozo (Virgin of the Well) and Sta. Ana Lao Ma (仙鬥撈媽 Mother of Sta. Ana) or Ma Cho Po (Mazupo 媽祖婆) of Sta. Ana. These three shrines to the Virgin Mary combine Catholic, Daoist, Buddhist, and folk elements.

At the side of the main Sta. Ana church is a small chapel where the Virgin of the Well is enshrined in bas relief. An ancient well was said to have spouted miraculous water even before the Spanish Christian era. It was reopened in 2012 after being sealed by health authorities for 92 years (from 1920) due to a typhoid epidemic caused by the contamination of the well.

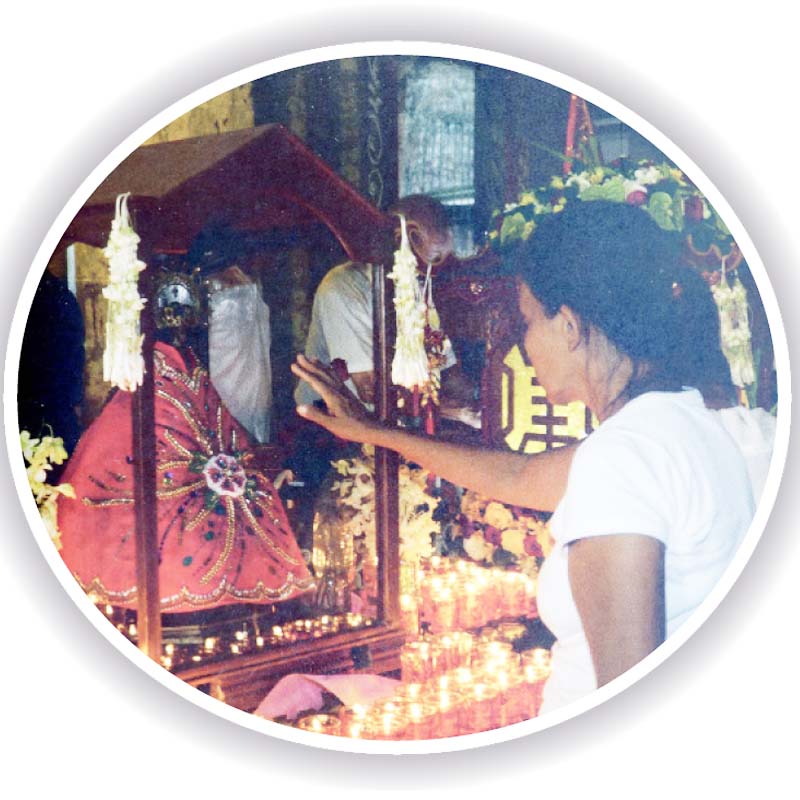

The Franciscan priests allow devotions to be carried out at this shrine, although it caters more to folk or popular religiosity, much like the use of the miraculous water in Marian shrines like the one in Lourdes, France. What is unique in this chapel are the Chinese incense sticks being sold at the door.

Filipino devotees offer red candles, light up three sticks and kowtow before the image in much the same way people do in Chinese temples. The devotees say that they are imitating the flocks of Chinese who used to worship at the shrine across the street.

The shrine across the street from the Virgin of the Well is that of the Mother of Sta. Ana (Sta. Ana Lao Ma). She is considered the same Lady of the Abandoned because early Chinese immigrants felt strongly that they were abandoned children who left their homes to seek better livelihood opportunities to support loved ones back in their Chinese hometowns.

The enshrined image is that of the Virgin Mary, but she is regarded by devotees as a manifestation of Guanyin (觀音 Chinese goddess of mercy) and Mazu. This is partly due to her Chinese name, Sta. Ana Lao Ma. While ma (媽) means mother, some devotees equate the ma with Mazu (媽祖) as evidenced by the holy card that the caretaker, Felix Go, gives away at the shrine. Go does not speak Chinese but he recalled that the Lady is at the same time called the Ma Cho Po (Mazupo 媽祖婆).

Though located in the vicinity of a Catholic church, the Church authorities have no jurisdiction over this Chinese shrine where the Virgin Mary, identified with Mazu and Guanyin, is venerated using Chinese ritual forms, and stands beside other objects of Catholic devotion. Even Filipinos often refer to some images of Virgin Mary as Guanyin Mary or refer to them as the “Chinese Virgin Mary.”

In the Philippines, statues of Guanyin and the Virgin Mary can share the same altar, and Chinese devotees tend to identify them with one another. To call Guanyin the “Chinese Mary” or the “Buddhist Madonna” is in fact an act of linking a local icon to a properly Chinese devotion.

Chinese people have a practical attitude towards religion. Their faith and beliefs have always been more tolerant of accepting outside influences. The pluralist nature of Philippine society and the harmonious blending of eastern and western influences in its culture also allow the Chinese much freedom in their religious preferences.

Fortunately for the Catholic Christians, though the syncretic practices are not officially sanctioned by religious authorities, the devotion of the followers and their strong faith in the divine guidance of the Mama Mary who is also Mama Ma Cho allows an integration of beliefs and religious practices.

In addition, the practices and positive influence of this unity of faith and beliefs go a long way in helping to enhance better understanding and tolerance among the Filipinos and the Chinese Filipinos in their midst.

Coming soon: Mazu in Manila

In October, 2018, 2,000 Mazu devotees from Taiwan and China traveled from the main Mazu Temple in Meizhou, Fuzhou (湄洲媽祖祖廟) to Manila.

To mark their arrival, there was a procession of the Mazu that began in Binondo and ended in Rizal Park.

The Philippines’ main organizer Irene Yang (楊端貞) is directress and trustee of the Ci Hang Chan Temple (慈航禪寺) in Sta. Cruz, which spearheaded the huge welcoming event. Yang mobilized the three key Chinese organizations in Manila: Federation of Filipino-Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry Inc., the China Chambers of Commerce in the Philippines and the Federation of Filipino-Chinese Associations in the Philippines.

They joined her in welcoming the delegation and parading the original Meizhou Mazu.

Yang said the visit of Mazu has led to the purchase of a 1,000-square meter lot on Tetuan Street, Binondo for a temple. Construction plans are being drawn with help from Meizhou.

The story of Ma Cho in the Philippines underlines the reality that faith and goodwill have become the underlying factors to the complete integration of two peoples and their religious beliefs.