Should we censor what our children watch and read?

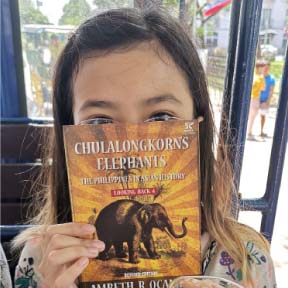

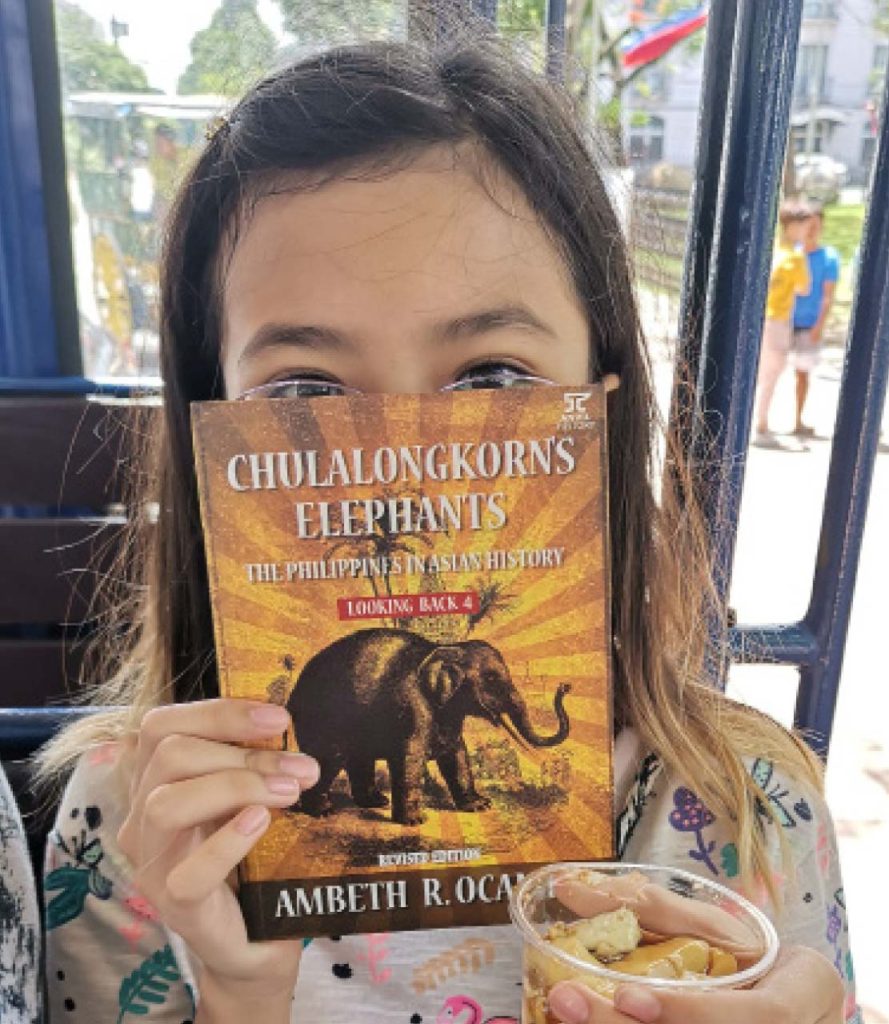

Achi began reading book one of a 13-book series last year. She stopped at book three and moved on to other books. She recently picked up the series again, and is going through them like candy.

Of author and historian Prof. Ambeth Ocampo, she says “He’s funny.”

She brought the books to read during the downtimes at ballet classes and rehearsals at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. A couple of parents asked if she really understood the books. They are, after all, about Philippine history, some of them even obscure events.

For one, Achi is a fan of history. For another, it is totally alright for her not to exactly understand the events in the articles she is reading.

She often goes online to research some more the events she finds interesting. Sometimes, she shares her new knowledge with us and asks me or Tatay if we know about it.

There would be some sort of question-and-answer session, which benefits Shobe as well.

She is also beginning to read some adult level fiction. She is interested in reading Angels and Demons by Dan Brown, after I gave her a summary.

There are quite a lot of gory details in the book and some very heavy violence. However, at this stage, I think it is more important for her to learn how to process these adult-level books.

She is currently in seventh grade, and reading beyond her grade level. There is no stopping her. Thus, it is doubly important to teach her how to read and how to think about what she reads.

Pretty soon, she will get hold of romance novels or suspense novels that have sex scenes. I want her to be able to react to this with neither fanfare nor drama.

I speak from experience. I accidentally read a book with a lot of sex in it when I was 13. I had no prior talks from any adult regarding sex, nor even kissing. Tsinoy schools don’t do that. Tsinoy parents don’t do that either.

Of course, I had seen television shows and movies, but in the 1980s, these were tame, and certainly nothing like what was in the book I was reading.

Likewise, I read Anna Karenina a year prior and even if the book was about a promiscuous wife and her affairs, the storytelling there does not compare to contemporary fiction.

Given that I knew nothing, and suddenly read If Tomorrow Comes by Sidney Sheldon, the shock was unbelievable. [I read the blurb at the back of the book and it said the story was about a thief!]

In contrast to my non-experience, Achi’s schoolteachers had already spoken to the class about reproductive health. I already taught her and Shobe about the physiological changes that happen when females get their monthly periods.

The key here is not to mask anything. We need to show our children, both male and female, that body parts are body parts.

Young children, especially, should learn that parts that are hidden under clothing should be kept hidden at all times from everyone else except their parents. But that even their parents are not allowed to touch these.

Beyond this, we should also teach the children the names of private body parts. The goal is for us to treat body parts as regular parts that help the body function. None of these parts are “bastos” or indecent in and of themselves. It is society that makes them so.

For example, in general Philippine society, children are taught to call the penis as “bird” and the vagina as “flower.” Giving other names to private parts convey a specialness and a mystery to these parts instead of making them just normal.

Using different terms also convey that we are very uncomfortable talking about our body parts. This heightens the mystery and the hesitation in speaking about our bodies.

Our general societal prudery actually leads to more harm than good. For example, a child in an urban poor community is sexually abused. While she has been taught about good touch and bad touch at the daycare center, the term used is flower and that the flower is special.

Abusers usually tell children that what they do is special and secret. This mystery surrounding the flower leads the child to think that the abuser is just following all the mystery surrounding the vagina.

Pair that with the general discomfort in speaking about body parts, the child then never reveals that she is being abused.

Let’s bring it back to reading and talking about sex. The same general discomfort prevails. We shelter our children from these conversations because most of us are not comfortable ourselves.

However, this general sense of secrecy surrounding sex is exactly what we, as parents, need to avoid.

I have written before that one of our life principles at home is “there are no secrets, only surprises.” When I shared this with my friends, they all joked that one day, my daughter will come home to say, “Surprise, I’m pregnant!”

But this is exactly what we are preventing. When the principle prevails, it means my children will talk to me about anything, including sexual relations. The rule is not enough though. My children should also be comfortable enough to broach this topic with us.

Hence, the openness and non-censorship. Being open about it means they don’t need to close their eyes when there are kissing scenes in a movie, or when the characters start shedding their clothes. Lately, they have learned to be embarrassed and would go “eeew” when characters start kissing or taking off clothes.

Tatay and I would just remark, “What eeew? It’s just kissing.”

They respond, “But they’re going to have sex!”

Us: “Which is nothing. They’re just going to have sex.”

Both girls have to be reminded that kissing and sex are nothing to be embarrassed about. These two actions are normal and they can talk to us about it any time they want.