Among the influences and contributions of the Chinese in the Philippines, especially during the Spanish and American periods, painting is seldom mentioned, except, of course, the art works done by Chinese artisans.

Recently, we were happy and fortunate to discover the Chinese influence and contributions on the famous 14 paintings of the basi warriors of Ilocos by Esteban Villanueva in 1821.

This valuable information is found in the coffee-table book Conscripcion: Imaging and Inscribing the Ilocano World (An Exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Manila, Oct. 17, 2011-Feb. 12, 2012) given to the Chinben See Memorial Library by the author himself, Ino Manalo, co-curator of National Archives of the Philippines. The entire painting collection is kept at the Burgos Museum of the Filipino Foundation Inc. in Vigan, Ilocos Sur.

For a short background on the Basi Revolt and the paintings of the basi warriors, allow us to cite the first three paragraphs of an article by Santiago A. Pilar, “The Basi Warriors: A Unique Revolt Recorded in Naïve Style,” in Conscripcion, which first appeared in Archipelago, 1976-V.

In 1786, the Spanish colonial government established its monopoly of wine in the archipelago. The imposition was galling, to say the least. Filipinos were accustomed to a hearty enjoyment of their homemade wines. The monopoly was reviled and resented, but it remained for the Ilocanos, the people of the northern provinces of Luzon, to rise in rebellion.

The Ilocanos’ drink was basi [it still is], a potent wine fermented from sugarcane juice. It was unthinkable that anyone should forbid the Ilocanos this basi.

On Sept. 16, 1807, the people of Piddog, Ilocos Norte took up arms. Their revolt in defense of basi, the only one of its kind in the annals of Philippine history, quickly ignited the neighboring towns.

But the basi warriors were crushed, the forces scattered, their casualties multiplied. What had begun in true fervor ended in crushing defeat that no small quaff of basi could quench.

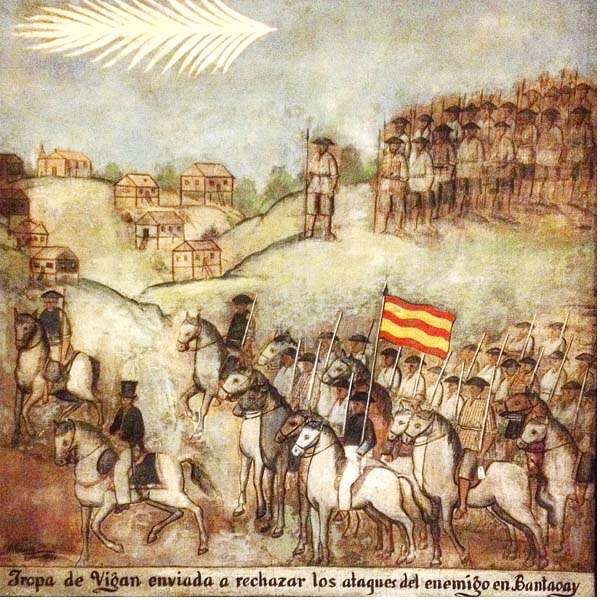

Later, to record the lengths Ilocanos could go for basi, the Spanish colonial government of the Ilocos provinces commissioned a painter, Esteban Villanueva, to make a chronological presentation of the battles and skirmishes. Villanueva made 14 paintings which are preserved in excellent condition today at the Burgos Museum in the city of Vigan.

Of the Chinese influence on Villanueva’s paintings, Pilar wrote:

Villanueva’s art is called ‘naïve’ in today’s terms. This implies that he conceived and created his art without taking formal lessons from established artistic traditions, particularly the Western. The label indeed becomes confusing, if one includes the Oriental canons within the scope of established artistic traditions.

It is, however, unavoidable to do so for Chinese painting was the most available tradition that greatly affected and taught Philippine painting especially at its incipience. Nevertheless, the ‘naïve’ and ‘Chinese’ elements in pre-19th century Philippine paintings are not so mixed up.

And in the art of Villanueva, those are easy to sort out. The convoluted clouds in some of the paintings are, for example, familiar elements, in Santos or religious images attributed to Chinese carvers.

The spontaneity of Villanueva’s brush strokes and his way of developing volume, as in the fruits and rumps of horses are reminiscent of free style with Chinese brush.

By the way, Villanueva’s life similarly rests in the shadows. A businessman, he belonged to the Villanuevas of Vigan, a big clan of Chinese-Spanish mestizos.

Also, from Conscripcion, according to the article of Romeo B. Galang Jr., “Re-visioning Ilocos:”

Towards the end of the century, references to the Chinese began to appear. The first was in 1883, when a Chinese Christian, Chapco Abaya, won the bid for undertaking the repairs of Episcopalian Palace of Nueva Segovia in Vigan.

Galang also said:

The records on the fire of Dec. 5, 1842 describe a part of the urban landscape of the pariancillo of the Barrio de Mestizos or the village of the Chinese half-castes.

By the later part of the 19th century, Vigan emerged as a cosmopolitan city, inhabited by Spaniards, Spanish mestizos, Chinese, Chino mestizos and Ilocanos. For purposes of tribute collection, the tribute payers are divided into three gremios: the Gremio de Chinos for the Chinese, Gremio de Mestizos for Chinese mestizos and Gremio de Naturales for Ilocanos…

Hence, there are indications that the members of the Gremio de Chinos may have been concentrated along part of Calle de San Jose, which was in the former Barrio de Mestizos. Incidentally, Calle de San Jose was the name of business center not only in Vigan but in other towns as well.

Our heartfelt thanks to Manalo for his Conscripcion. It enhances our knowledge on Chinese in Philippine paintings and Ilocos.