Whenever Dr. Jose Rizal traveled across Germany and Switzerland, his friend and traveling companion, Dr. Maximo Viola, noted that Rizal always carried a small bag containing his personal letters. Asked why he treasured his letters so much, Rizal responded that he gets a glimpse of the character and mood of the family and friends through the letters, as well as noting the changes in their lives.

Whenever Dr. Jose Rizal traveled across Germany and Switzerland, his friend and traveling companion, Dr. Maximo Viola, noted that Rizal always carried a small bag containing his personal letters. Asked why he treasured his letters so much, Rizal responded that he gets a glimpse of the character and mood of the family and friends through the letters, as well as noting the changes in their lives.

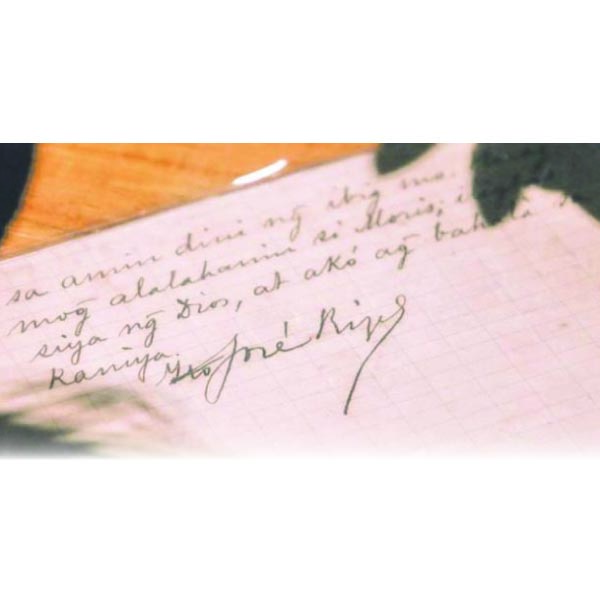

In 2011, the National Heroes Commission published a book containing those precious personal letters as well as of his responses. It was simply entitled Jose Rizal: Letters with Family Members.

The letters have been published before, but in Spanish – part of a mandate set by the Rizal National Centennial Commission to publish all the works of Rizal not only in their original language, but also in English and in principal languages of the Philippines.

Readers might think the appeal of this book is limited only to those in the academe and researchers of Philippine history and culture. But even casual readers will find the book a compelling read as it shows how Jose Rizal transformed from an innocent student studying in Europe to a martyr.

One can glimpsed a more human image of Rizal from the book.

In one letter, his sister Maria wrote how much her children miss their uncle and how they would try to outshout each other to express their “ownership” over their uncle.

Another letter reveals how Rizal coped with homesickness by urging his sisters to write more often. He humorously suggested that if they are afraid to write more often because of the cost, they could “put together all your letters in one envelop and weight them, if they are less than 15 grams, then they will not require more than one stamp.”

What I like about this book is how Rizal’s voice and those of his family come across unfiltered. I can make my own conclusions without the bias or agenda of writers or historians.

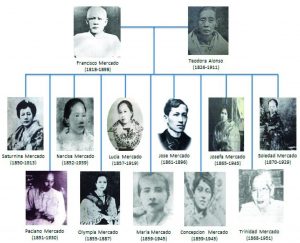

Though the book offers no new revelations about Rizal and what he advocated, the most important thing that emerges, for me, is how much Rizal’s family played a role in his decision-making. It was as if Rizal would not have become the person he is, had it not been for his family standing by him and supporting him, all the way up to his execution.

Though the book offers no new revelations about Rizal and what he advocated, the most important thing that emerges, for me, is how much Rizal’s family played a role in his decision-making. It was as if Rizal would not have become the person he is, had it not been for his family standing by him and supporting him, all the way up to his execution.

One way Rizal’s family helped shaped his destiny is how they guided him in making major decisions. I used to think that the decision for Rizal’s studying medicine in Europe was his parents’ decision: all Rizal needed to do was board the ship and leave for Europe.

So, it was a surprise for me to discover that it was a decision made between him and his brother Paciano. In fact, Paciano wrote to Rizal about how his parent grieved when he received the telegram that Rizal had already left for Europe. His father was inconsolable.

Paciano wrote that… “the old man became taciturn, always staying in bed, and weeping at night, and the consolation offered by the family, the curate and strangers was of no avail.”

Paciano eventually figured out that what was worrying their father was how Rizal was to finance his study in Europe. It was only after Paciano revealed to his father how they were able to work out the financing that he was able to return to his usual ways.

As you read the letters you also gain an understanding of how life was like for the people in the Philippines during the late 19th century: their manners and customs, their lifestyle and their means of livelihood.

For example, how Rizal’s family financed his studies in Europe. It was due to sugar. In several of the letters, the main topic revolved around the price of sugar.

In 1884, Rizal warned his family about an impending treaty that will allow the entry of Puerto Rico and Cuban sugar into the US market. If the treaty is passed, Rizal knew it will affect their family income.

He then wrote that perhaps he should go home, and with the training he has received, set up a medical practice in a town of Calamba. We know that Rizal did not do so. He stayed on in Europe and eventually specialized in ophthalmology.

The letters are arranged chronologically and are preceded by a short description. Still, it would be advisable for readers to have an idea of the timeline of Rizal’s life.

For example, in one letter written in 1883, Rizal wrote how often he was mistaken in Spain as either Chinese, American or mulatto (of white and African parentage).

He was dismayed to find out that even Spanish students were not aware that the Philippines was a colony of Spain. It was here that I realized that at this point in his life, Rizal was already struggling with his identity of being a Filipino and how the Spaniards viewed their colony.

This question about the Filipino identity resurfaced in another letter to his parents two years later. This time Rizal was asked if the Filipinos would fight in defense of the Spanish flag against the Germans.

Here we see a more mature Rizal when he answered, “We would always fight in fulfillment of our duty and in obedience to our conscience.” As to what is our duty and what does our conscience dictate, Rizal’s reply: “Our duty… is to love our country and our conscience dictates that we do everything that our duty implies.”

Sometimes I wish the book would supply us the reaction of the receiver of the letter.

For example in one letter from Hong Kong, Rizal wrote how he did not regret publishing Noli Me Tangere, even as it brought suffering to his family. “I know that I have made you suffer greatly, but I am not repenting of what I have done, and if I had to begin anew, I would again do the same thing that I did, because that is my duty…Men ought to die for his duty and his convictions. I maintain all the ideas that I have expressed concerning the state and the future of my country, and I will die gladly for her, and nay, to obtain justice and tranquility for you.”

Whether these words brought courage to his family or made them question his sanity, we can only speculate. Perhaps they were indeed angry with him, which is perhaps why he softened his next letter to his mother with a bit of humor.

Arriving in Dapitan, he tells his family it was as if he were on vacation. But he does add that the things that he misses the most are his family and freedom.

A lot of the letters during Rizal’s Dapitan days mixes family updates, inquiries, advices and requests. But reading between the lines, one might sense that there were some doubts within the family if Rizal is doing the right thing.

In a May 1895 letter, Rizal told his sister Trining to have more confidence in him and not treat him as a child who has to be guided in everything. “If my family has no confidence in me and always treats me like a child, how will others treat me and what confidence will they have in my judgment? I’m in the hands of God and until the present I have no reason to say that He has abandoned me. Let us do always our duty, what is right and let Him do the rest. Let us not be hasty in our judgment, but let us think well of our fellowmen.”

Towards the end of his life, it was apparent that Rizal’s family stood by his side, no matter what the cost. A day before his execution, Rizal wrote that he wanted to see the bravest member of his family with him before he died.

Responding to that request was his youngest sister, Trinidad, who visited him along with Rizal’s partner Josephine Bracken. His brother Paciano was unable to be there.

In a personal letter, Rizal apologized for leaving him the burden of taking care of their parents and family. In his last letter to his family, Rizal encouraged his family to live in peace and asked them to pity his partner Josephine.

The book shows that the people we surround ourselves with determine the destiny we will end up with. Readers may wonder what sort of “reward” Rizal’s family got in supporting their brother Jose?

It is this: they have earned their place in Philippine history and their support, encouragement and sacrifice are recalled every time we study about the life of Jose Rizal.

Definitely, being a hero is a team effort.