To five million Chinese Americans, the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA 美國華人博物舘) is an important repository of their community’s memories and history. Since it opened in 1980, the MOCA has become the place for Chinese Americans to share with the rest of the world how history and culture helped shaped their identity.

The museum was started by Chinese-American historian John Kuo Wei Tchen and community activist Charles Lai. It was originally a New York Chinatown History Project, with the aim of documenting the history of New York’s Chinatown.

When it first started, the museum and research facility were both housed in a building on New York’s Mulbery Street. Then, in 2009, the museum was moved a few blocks away to its new location at Center Street. The research facility was retained at the building on Mulberry Street.

The current museum is housed on the ground floor and basement of two commercial buildings, with a floor space of 16,000 square feet. The museum design is simple and it is easy to navigate through the whole exhibit. One has the option of booking a guide ahead of time and learn more added bits of history and insights.

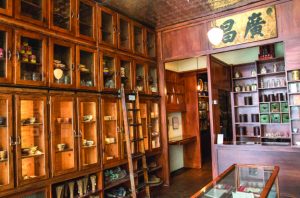

The centerpiece of the museum is the main exhibit entitled “With a single step: Stories in the making of America.” The story of the Chinese American is then told through the use of archival photos and artifacts. Description and additional information are supplied by video projections on the walls and glass partitions.

Also featured are the life stories of Chinese Americans from various historical periods, meant to serve as examples of what it meant to be a Chinese in America at different times in its history. At the same time it is also meant to examine America’s journey as an immigrant nation.

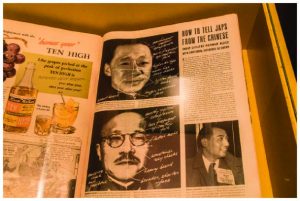

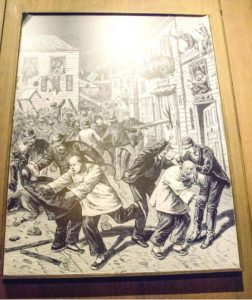

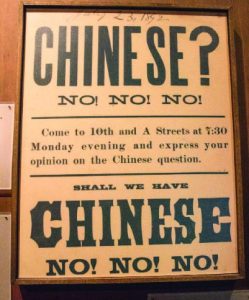

The exhibits begin with how the Chinese began arriving in the United States in the 1800s. Many of them were mostly men who worked in the mines or helped build the country’s railroad. When the US economy experienced a downturn in the 1850s, the Chinese laborers, who were willing to work for lower wages, were viewed by American laborers and unions as a threat to their jobs.

This fear led the US government to pass the Exclusion Act in 1882, which denied entry to coolies and common laborers: only skilled tradesmen and craftspeople were allowed, which limited the migration of Chinese to the US and their territories.

Understandably, the Chinese Americans were not happy with the passing of this law and their displeasure was made known to the American public through such activists as Wong Chin Foo and Du Lee.

These activists also tried to win support from the American public and dispel their misconceptions about the Chinese through public debates and newspaper editorial pages.

Despite the hostility towards the Chinese, there were some who managed to rise above it. One such person was Faith Sai So Leong, the first Chinese American female dentist during the early 1900s.

Another fascinating story is that of Chinese American actress Anna May Wong. Daughter of a laundry man, she became a film actress in the 1920s and 1930s.

During my visit to the museum, I listened to a recording of her struggle about being typecasted as an Asian temptress. One of the restrictions imposed on her was that she was not allowed to play romantic scenes unless it was with an Asian actor.

The Exclusion Act limited the type of work open to Chinese migrants. Many ended up working in laundry shops and Chinese restaurants. The Exclusion Act was finally repealed when the United States entered World War II. Only then did opportunities open up for the Chinese Americans. But even so, there were still plenty of challenges.

The latter half of the exhibit shows how the community was affected by geopolitical issues during the second half of the 20th century: such as China becoming a communist state, the Cold War and President Nixon’s visit to China. Still, despite these challenges, the Chinese Americans were able to leave their mark in American society and thrive in fields as diverse as politics and literature.

Aside from the main exhibit, the museum also serves as a venue for short term exhibits. One memorable exhibit, held in 2016, was entitled “Sour, sweet, bitter and spicy.” It explored the linkages between Chinese food and identity in America, using the medium of ceramics and video installation for its presentation. The museum has also become a venue for talks and lectures, with topics usually related to the ongoing exhibits.

The museum also has a gift shop that sells souvenirs and books that cover the various topics related to the Chinese American community. Worth buying is the museum’s neighborhood map of New York’s Chinatown to help you find your way around. You can also book a walking tour of Chinatown at the museum.

Once you are done with the main exhibit on the ground floor, you can move on to the basement. For me, this is one of the more interesting spaces within the museum. The architect of the museum, Maya Lin, deliberately exposed the brick walls of the basement. She then added a sunlit sky roof so as to reference the courtyard found in many traditional Chinese houses.

The basement is of particular interest to those with children. It is a sort of half-playground, half-exhibit area. According to the museum’s brochure, this is where family activities are held twice a month. These can be anything from storytelling to arts and craft workshops to artistic performances. It is also here that children learn more about Chinese culture and Chinese American history through interactive play.

One section enables children to smell and taste the various condiments used in Chinese cuisine. Another section provides clothes for playing dress up. But the aim here is to share with kids the many Chinese Americans who have worked in the American garment industry.

As interesting as the MOCA’s narrative is, I can’t help but feel that there is a gap. The Philippines was a US territory for 38 years, from 1898 to 1946. Despite this, I did not find anything in the museum that discuss how the US treated the Chinese in the Philippines, or even in other US territories at that time, such as in Hawaii.

Since the Exclusion Act was also applied in the Philippines, this would explain why we have one of the smallest Chinese communities in Southeast Asia – predominantly from Fujian province.

Perhaps someday, the MOCA will collaborate with the Bahay Tsinoy Museum to come up with an exhibit to cover this gap.