The Ming Dynasty imperial eunuch Cheng Ho (Zheng He in pinyin 鄭和 1371-1433), with his mighty fleet of 300 ships, sailed seven times to the Western Ocean from China from 1405 to 1433. The fleet visited countries in Southeast Asia, Indian Ocean, Middle East and all the way to Africa. His ships were so big, the ships of Christopher Columbus (he had three on his first voyage) and Vasco da Gama (four) together could have easily fitted on the deck of one vessel.

The Ming Dynasty imperial eunuch Cheng Ho (Zheng He in pinyin 鄭和 1371-1433), with his mighty fleet of 300 ships, sailed seven times to the Western Ocean from China from 1405 to 1433. The fleet visited countries in Southeast Asia, Indian Ocean, Middle East and all the way to Africa. His ships were so big, the ships of Christopher Columbus (he had three on his first voyage) and Vasco da Gama (four) together could have easily fitted on the deck of one vessel.

Cheng Ho’s voyages took 28 years to reach 37 countries in Asia, Middle East and Africa. He traveled a total distance of 130,000 nautical miles, which is estimated to be equivalent to circumnavigating the globe three times. It is the world’s earliest, biggest and historically the longest and farthest expedition ever undertaken. It opened China’s ancient maritime silk route for economic, cultural and political exchanges with distant partners (see Tulay March 3-16, 2015 issue on the Ming Empire and Zheng He’s voyages).

Cheng Ho’s fleet followed the Western Ocean route, so he and his men never set foot on the Philippines, which was in the Eastern Ocean route.

Of the Southeast Asian countries, Melaka was visited the most number of times: five out of the seven voyages. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is a small cultural museum built there in his honor. The impact of his trips was far-reaching. In fact, he is even venerated as a folk deity in some parts of Southeast Asia.

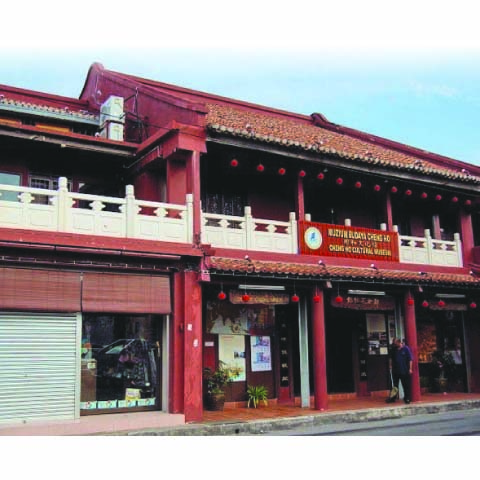

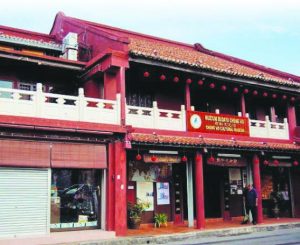

The Cheng Ho Cultural Museum (鄭和文化館) was built after the discovery of a cluster of three Ming Dynasty architecturally-styled mansions along the Melaka River bank in 2000. Historical relics, such as a stone well with a unique locking system used only by early Chinese officials, were found in the area.

The well head is different in construction from those of the colonials but similar to those in Cheng Ho’s home province of Yunnan. Inside the well were artifacts such as a huge incense burner, food storage urns, and Ming dynasty ceramic shards and coins.

Convinced that most of the ancient ports are located at river mouths, Tan Ta Sen, president of the International Zheng He Society in Malaysia, did intensive research and confirmed that the area was indeed the mysterious location of the warehouse complex, or Guan Chang (官廠), mentioned in Ma Huan’s book Ying Yai Sheng Lan (瀛涯勝覽).

Ma Huan, an interpreter who accompanied Cheng Ho on several of his voyages and had written very detailed descriptions of the voyages, described the warehouse or Guan Chang:

Whenever the treasure ships of the Middle Kingdom [China] arrived there, they at once erected a line of stockades, like a city wall and set up towers for the watch drums at four gates, at night they had patrols of guards carrying bells; inside, again they erected an inner stockade, like a small city wall, within which they constructed warehouses and granaries; and all the money and provisions were stored there. The ship which had gone to various countries returned to this place and assembled there. They marshaled the foreign goods and loaded them into the ships; then waited till the south wind was perfectly favorable… and returned home…

In 2003, Tan opened the museum in the completely renovated shop houses, with the wooden carvings in the old mansions preserved. They followed Ma Huan’s descriptions of the Guan Chang to reconstruct the façade and interior of the museum.

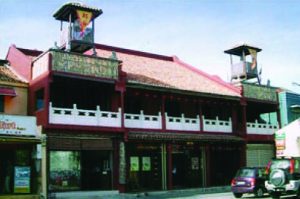

For instance, a pair of watch towers (drum and bell tower) at the front of the museum was constructed, just as they were described by Ma Huan in his book, although these have been subsequently removed.

In 2005, Tan published a book on Cheng Ho’s voyages to Melaka. Both the museum and the book are not without controversy:

Some in the academic community have doubts regarding the authenticity and appropriateness of some of the displays as well as inaccuracies and exaggerations in the book, especially about the journey reaching the Americas. However, the government and the Melakans laud Tan for his dedication and efforts in putting up the museum.

A blue and white moon gate marks the entrance to the museum’s main hall. The first exhibition gallery is the Ming Court Gallery. The long corridor is lined with exhibits from Cheng Ho’s life, from his home province in Yunnan, Beijing, Nanjing and Fujian.

A replica of a stele of Tien Fei (天妃) found in Changle, China dominates the corridor. Another stele contains the inscription of Emperor Yong Le recognizing Melaka as a State. Porcelain shards and artifacts dug up from the mansions were displayed on the opposite side of the corridor.

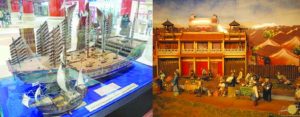

Of great interest to me when I visited was the Melaka Gallery exhibiting the products of the Sino-Malay exchanges and their influence on agriculture, fishery, industry, and trade and commerce. A model of the entire Guan Chang as described by Ma Huan dominates this gallery. It also has a brief description of the visit and untimely death of the Sultan of Sulu when he paid tribute to Emperor Yong Le in 1417.

The next two galleries contain a replica of Cheng Ho’s mother ship, scientific navigation charts, instruments, communication equipment and other memorabilia. A captain’s room and a tea house offering Chinese and Malay delicacies capped the visit.

The museum is a welcome addition to the many other historical sites, housed in converted heritage mansions in the main tourist-filled Jonker Street in Melaka.