“Why do we question the presence of a statue that pays tribute and memorialize the sufferings and sacrifices of our Filipino mothers and yet allow the presence of shrines that commemorates soldiers who killed our compatriots?”

Many organizations raised this question more vociferously after the stories about the Comfort Woman Statue came out in the news.

It is reported that in all the shrines, Japanese officials and tourists would arrive in buses or in vans and pay respect to their dead. Ironically, some of these shrines were built by our own government with support from the Japanese.

1. Kamikaze Peace Memorial Shrine in Mabalacat, Pampanga was erected by local tourism officials in 1974 at the former site of Mabalacat East Airfield. The monument had a sign in English with the words “Kamikaze First Airfield Historical Marker” and had an inscription in Japanese with the following words, “Airfield where Kamikaze Special Attack Corps aircraft first took off in World War II.”

1. Kamikaze Peace Memorial Shrine in Mabalacat, Pampanga was erected by local tourism officials in 1974 at the former site of Mabalacat East Airfield. The monument had a sign in English with the words “Kamikaze First Airfield Historical Marker” and had an inscription in Japanese with the following words, “Airfield where Kamikaze Special Attack Corps aircraft first took off in World War II.”

The Mabalacat Tourism Office rationalizes that it supports the establishment of the shrine not for the glorification of the Kamikaze but rather for the use of war history as a tool for the promotion of peace and friendship among nations. This shrine serves as a reminder that the Kamikaze phenomenon shall never happen again.

The Kamikaze was a special aviation unit of the Japanese military during WWII. Its pilots went on suicide missions against naval vessels of Allied forces.

On Oct. 25, 2004, a life-sized Kamikaze pilot statue was unveiled atop a tall pedestal in front of a wall that shows the Japanese rising sun flag on its right half and the Philippine flag on its left half. The lot also has a torii, traditional Japanese gate, entrance by the street.

2. Japanese Garden at Cavinti, Lumban, Laguna is a memorial park covering 11 hectares of land built by the Japanese government in the 1970s to commemorate the Japanese soldiers who died during WWII. It is popularly known as the Japanese Garden at Caliraya, Laguna but it is in fact atop a mountain in Lumban, Laguna that overlooks Lake Caliraya.

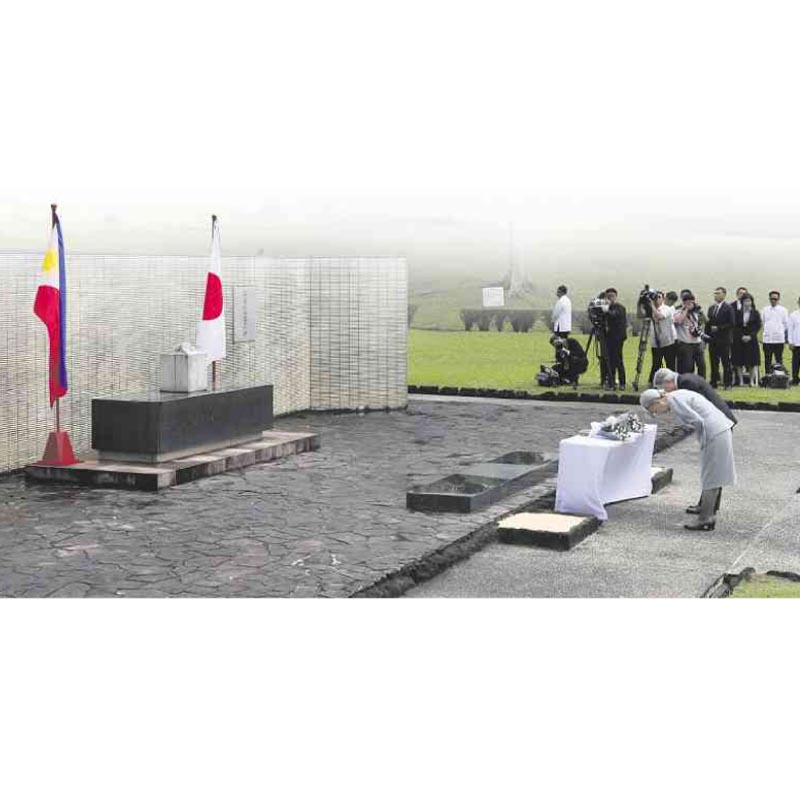

On Jan. 29, 2016, Japan’s Emperor Akihito with Empress Michiko offered flowers at the marble altar located at an elevated portion of the garden. In a half-hour event aired live in Japan by public broadcaster NHK, the imperial couple spoke and shook hands with former Japanese soldiers as well as relatives of their comrades killed in the Philippines.

The royals were on a five-day visit to the Philippines to celebrate 60 years of diplomatic ties and honor those who died during the Japanese occupation.

Japanese tourists and descendants of the soldiers offer prayers and gifts to the spirits of the dead soldiers at this shrine/altar.

3. Japanese Memorial Garden in Corregidor Island pays tribute to the 6,600 Japanese soldiers who died and were buried in Corregidor Island during WWII. It serves as a praying ground for Japanese war veterans and families of the deceased. The garden features many Japanese markers, relics of anti-aircraft guns, and shrines.

The marker itself is often vandalized by Filipino and American visitors to Corregidor who are enraged by a shrine located on the island where the resisting Filipino and American soldiers died and/or were tortured and suffered most. The topmost part of the marker used to have additional characters denoting Japanese soldiers but apparently, a Filipino visitor sliced it off with a sword so that only the lower part, a generic marker for the dead, was left.

The construction of this garden was made possible through funds generated by a Japanese veterans Southern Pacific Memorial Association with support from the Japanese government in 1987.

4. The Japanese Shrine in Muntinlupa, located at the end part of the local cemetery in the National Penitentiary (New Bilibid Prisons), Muntinlupa is dedicated to the Japanese soldiers who died or were executed and buried in Muntinlupa and neighboring towns. It was former Mayor Jaime Fresnedi of Muntinlupa who had it erected in March 1, 2005.

5. Japanese soldiers’ shrine in Bulacan is erected in a 500-square-meter compound on Don Pedro Street in Barangay Marulas, Valenzuela, Bulacan. The original property used to be several hectares, used as a Japanese garrison and cemetery. It was mostly given back to the Philippine government as part of war reparations during the administration of the late President Elpidio Quirino. Only a small compound was retained in memory of their war dead.

The late Francisco Valenzuela was assigned by the Japanese embassy in Manila as the caretaker after the shrine was built in 1960. His daughter, Leonarda “Aida” Valenzuela, 70, took over as caretaker when her father died. They are paid a small stipend by the Japanese Embassy to take care of the shrine. In exchange, they were allowed to build houses for themselves and their families inside the compound. Aida said that Japanese still frequently visit the shrine, bringing saké, flowers and joss sticks and light them up, clasp their hands, and bow in prayer to honor their ancestors.

The local officials reportedly wanted to convert the place into a theme park or tourist spot. But Aida said “the place is sacred to them (Japanese) and they won’t allow it to be touched.”

Fourth-generation members of the Valenzuelas now look after the shrine.