A s a Tsinoy, I get the best of both worlds. When it comes to food, Filipino and Chinese cuisine are both commonly served at home. Filipino dishes are abundant in flavor – it can be something as simple as tuyo (dried fish) with tomatoes and salted egg or something saucy such as beef caldereta. Tsinoy dishes like pata tim (stewed pork leg) or mapo tofu (spicy tofu) are also an adventure for the palate. But one thing is common between the two cuisines – they are great served with steaming rice.

A s a Tsinoy, I get the best of both worlds. When it comes to food, Filipino and Chinese cuisine are both commonly served at home. Filipino dishes are abundant in flavor – it can be something as simple as tuyo (dried fish) with tomatoes and salted egg or something saucy such as beef caldereta. Tsinoy dishes like pata tim (stewed pork leg) or mapo tofu (spicy tofu) are also an adventure for the palate. But one thing is common between the two cuisines – they are great served with steaming rice.

Rice is the staple food for many Asian countries. For most Filipinos, if the viand is extra delicious or if they’re extra hungry, then the occasion certainly calls for extra rice. It is such an important and common part of our diet, that it is often taken for granted.

The Department of Agriculture even had a commercial campaign saying: “Kainan na at syempre, hindi kumpleto kapag walang kanin…palay, bigas, kanin, ‘wag sayangin (Time to eat but of course, it’s not complete without rice… avoid wasting rice).”

The cultivation of rice is considered one of the most important developments in human history. There are many schools of thought as to where rice first originated.

Nature.com has a 2012 study on the genetic material of rice which showed that rice was first domesticated in the Pearl River region in southern China. Other scholars believe rice originated in India.

There was a study published in open-access journal Nature Communications that says archaeologists found rice in the dung of dinosaurs in Pisdura village of Chandrapur district in Maharashtra, the western region of India. This means dinosaurs were enjoying rice long before humans.

Rice legends

In literature, there are a few legends on the origins of rice such as this Javanese folklore, as retold in Alice M. Terada’s The Magic Crocodile and Other Folktales from Indonesia.

Bataru Guru, lord of all gods, wanted to build a new meeting house, and all the lesser gods were assigned tasks to complete it. Gods contributed wood, sand and tiles.

The god Narada saw that they were busy with the project except for the snake god, Anta. Anta was sad because he cannot help.

“I have no arms or legs,” he said.

He shed three tears which became three eggs when they touched the ground. Narada suggested he bring the eggs to Bataru Guru as a gift and at the same time apologize that he is not able to serve.

Having no arms or legs, Anta picked up the three eggs with his mouth and went on his way. The garuda bird saw his friend Anta slithering and greeted him. But Anta could not greet the garuda bird back because his mouth was full, which made the bird feel insulted.

The bird attacked Anta with his claws and beak and made Anta let go of two of the eggs. His pride intact, the garuda bird then left the bleeding Anta.

Badly wounded from the attack, Anta presented the remaining egg to Bataru Guru. Bataru Guru then told Anta to take care of the egg. After some time, the egg hatched and produced a lovely baby girl and was named Sang-Hyang Sri.

Bataru Guru raised Sang-Hyang Sri as his and his wife’s own. Sang-Hyang Sri grew to be a beautiful young lady, and Bataru Guru decided to take her as his wife.

The gods were horrified at this impending incestuous relationship and poisoned Sang-Hyang Sri to prevent it from happening. The death of the princess made everyone sorrowful.

But days after her body was buried, the gods were astonished to see plants grow in the spot where she was buried. A coconut tree came out of her head. Rice plants came out of her eyes. And, as the story concludes, the rice plant then became the staple food of Indonesia.

The Philippines also has her share of origin myths. The Ibalois is one of the indigenous peoples living in Baguio. The Ibaloi tale is extracted from the book of Claude Russell Moss titled Nabaloi Tales.

Old man Labangan fruitlessly fished and hunted for food all day until he felt starved. He cried out to Kabunian, the supreme god of the Ifugao tribe, for food.

Kabunian then dropped a rope and pulled Labangan up to the sky and fed him rice. Of course, Labangan had never seen rice before. He stole a good grain of rice after rejecting the bad grain that Kabunian gave him and hid it in his hair, but Kabunian found it. Then Labangan hid it under his tongue when Kabunian unsuccessfully tried to search his mouth. Afterwards, Labangan planted the first grain of rice on earth. And everyone had enough to eat.

Usage of rice

Usage of rice

Rice impacts different groups of peoples as well. Glutinous rice plays a major role in other cultures such as Laos and northeastern Thailand where it is sometimes used for desserts and special foods for religious ceremonies.

Rice is also used to make alcoholic beverages such as the Japanese sake. To the Kachins of Myanmar, the rice mash at the bottom of the container is offered to a newly captured wild elephant. They believe that the animal will be forever loyal to the person who gave the food.

In Chinese language, rice is translated as 飯 (fan). To eat is to 吃飯 (chi fan). If one is to translate 吃飯 literally, it means “eat rice.” If you saw something gross and lost your appetite, a good 成語 (cheng yu) or four-character idiom to use to impress your Chinese-speaking friends would be 茶飯不思 (cha fan bu si), or literally, “to have no thought for tea or rice.”

It just goes to show how rice is a staple food in China, although often, a good bowl of noodles would do for many. Then again, in Chinese menus, 粉 (fen) is also referred to as “rice noodles” or “rice noodle wrappings” in 腸粉 (chang fen).

So vital is rice in countries where it is considered a staple food that a rice shortage is considered an economic disaster. That is why we have rice supply ensured by the National Food Authority, a government agency in the Philippines responsible for ensuring food security in our country.

Bluntly speaking, NFA rice is “cheap” rice to others because it doesn’t taste as good as the sinandomeng variety. Then again, taste is relative. Texture-wise, it is broken rice, meaning it is softer in texture and easier to chew.

And because of its nutty texture, some liken it to coarse couscous (an African dish made from another grain: durum wheat). Broken rice is commonly marketed/consumed in West Africa because it is cheaper.

Rice currency

By the 16th century, debts and taxes were collected in rice. Workers received rice as payment. Retainers and attendants of feudal lords received rice stipends.

However, it was inconvenient to be carrying sacks of rice around, so government authorized payment orders to rice warehouses or rice notes were issued instead. Rice currency survived in some of the remote villages of Japan up to the eve of World War II.

Burma measured its revenue in baskets of rice during the 19th century. The Burmese ate the good rice and used the inferior broken rice unsuitable for food or seed as money.

Rice was the most important primitive currency in the Philippines as well. In 1775, the sultans of Magindan collected taxes from the Philippines in unthreshed rice or palay.

In 1739, the colony of South Carolina made rice an acceptable means for paying taxes. The government issued “rice orders” to public creditors, which were redeemable after taxes were collected in rice. These rice orders circulated as money, and long-term contracts were struck in terms of rice.

There are other reasons why rice has a rich history as a form of money: as a commodity, rice was easier to transport than others, and could be stored up to eight or nine years.

Rice also served the monetary functions of a medium of exchange and its store value was better than most monetary commodities.

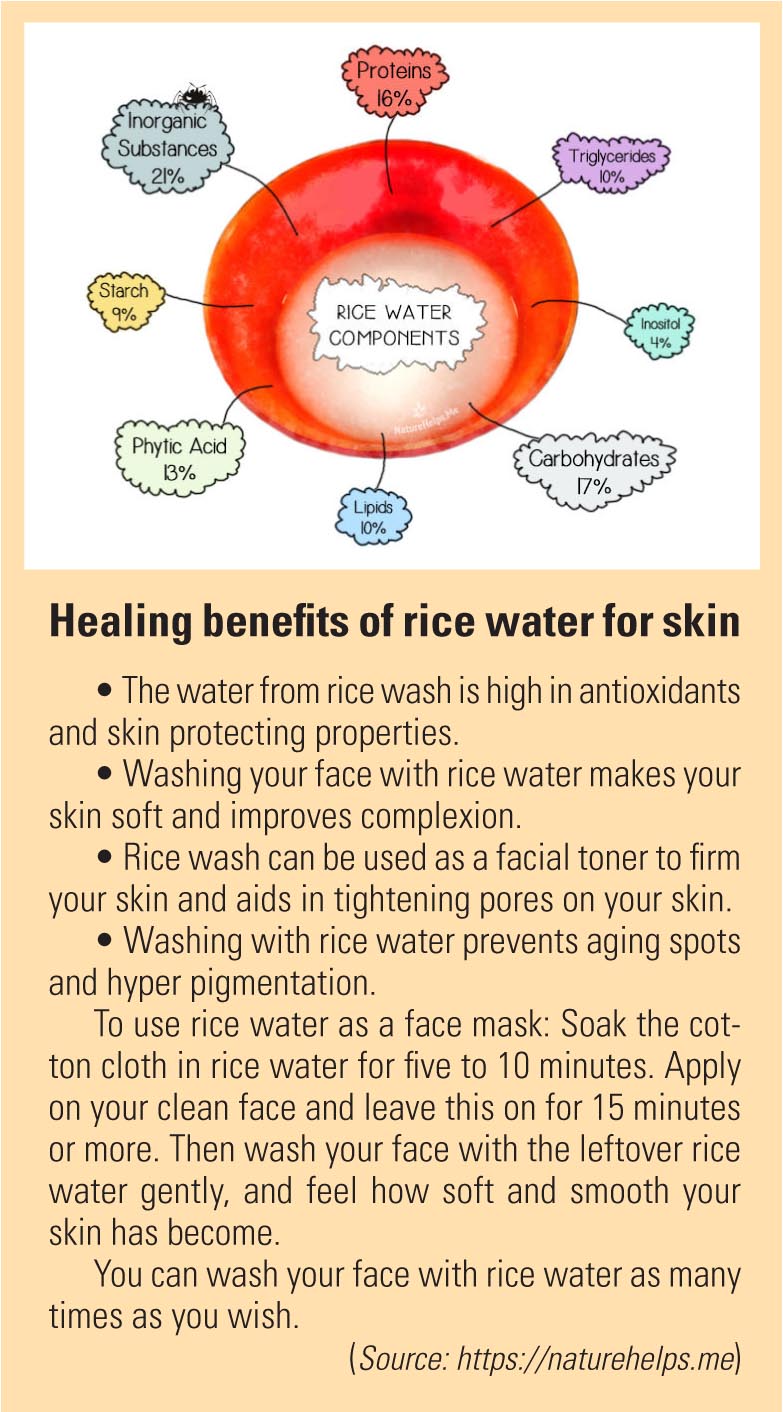

Other uses of rice include: milk for the lactose-intolerant and beauty products. Fans of Korean cosmetics will attest to these products which attribute their effectiveness to the “ancient beauty secrets” of using rice and ginseng, among others.

Future of rice

Looking at the present and future, continuous research on managing rice capacity is crucial. Politically and economically speaking, it plays a role in alleviating poverty all over the world. The wave of immigration to western countries also opens up new consumption patterns for rice.

According to the International Rice Research Institute in Los Baños, Laguna, an additional 40 million tons of rice is needed to feed the world’s growing population in the next decades.

Growing appetite for rice also results in the tightening of supply. Hence, scientists are exploring Africa to meet demands.

In 2008, a rice capacity-building program, Coalition for African Rice Development, was launched to support national rice development strategies. Part of CARD is an eight-week training course hosted by the Philippine Rice Research Institute in Nueva Ecija. The partnership will run until 2019.

This year, 19 African farmers graduated from the program where they were taught land and seedling preparation, harvesting, post-harvesting practices and quality seed management.

In China, scientists have also been doing research on breeding new strains of high-yield hybrid sticky rice. Many traditional Chinese dishes such as the glutinous rice dumplings make use of sticky rice, and just like regular white rice, the market for sticky rice has been expanding.

According to China Education and Research Network, a strain developed last 2005 has replaced majority of the paddy fields in China for long-grained non-glutinous rice.

China has been actively researching techniques on how to increase rice output and raising the so-called “super rice.”

Professor Yuan Longping became known as the “Father of Hybrid Rice,” narrated a famous dream he once had: “I saw rice plants as tall as Chinese sorghum (a flowering plant). Each ear of rice as big as a broom and each grain of rice as huge as a peanut. I could hide in the shadow of the rice crops with a friend.”

His dream finds reality in new varieties of high-yielding hybrid rice.