Six hundred years may be a drop of water in the vast ocean of time and memory, but the historical ties that bind our two nations and our two peoples will endure.

Seven years ago, 40 Filipino adventurers led by Art Valdez sailed around the Philippines and Southeast Asia aboard three replicas of our ancient balangay boats.

The team left the southern corridor of Tawi-Tawi in September 2009, crossed to Malaysia, traversed through Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, up to the territorial waters of Vietnam. The journey took 17 months.

The team had planned to reach China, but changes in the monsoon weather and weary crewmates longing to be with their families saw us back home in January 2011.

The front pages of most major newspapers featured the amazing feat. Then President Benigno Aquino III feted the entire crew at Malacañang; the city council of Butuan, where the original balangay boats were unearthed, declared them honorary Butuanons.

Of the three balangay boats, Diwata ng Lahi, was loaned to the National Museum and was declared as Important Cultural Property. She is currently on display at the museum grounds.

Masawa hong Butuan, named after the ancient kingdom and current city in Mindanao, was returned to where she was first built, at the Luna Compound, beside the mighty Agusan River.

The last boat, Sama ng Tawi-Tawi, named in honor of the boat builders from the Sama Dilaya tribe of Sibutu and Sitangkai in Tawi-Tawi, sat patiently near the shores of Bacolod City, awaiting her call to sail again.

The balangays

Two new balangay boats were constructed last April in Maimbung, Sulu by seven members of the Sama Dilaya tribe led by master boat builder Nur Usman. The Sama Dilaya are great artisans, craftsmen and carpenters.

The balangays were built without any blueprints. We simply gave them the length and width of the boats and they got to work; each boat was completed in 30 to 45 days.

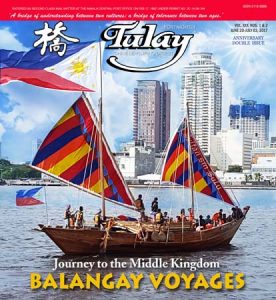

The two new balangays, Sultan sin Sulu and Lahi ng Maharlika, sailed to Zamboanga City last May 10. They proceeded to Bacolod City and were joined by Sama ng Tawi-Tawi and together traveled to Manila over a total distance of about 1,000 kilometers.

The boats mostly had the same crew from the 2011 voyage, plus a few new select volunteers. Majority of the crew are composed of Philippine Coast Guard personnel plus cadets from seafaring academies who have already undergone sea training and are familiar with most things maritime.

(Note: Of the three balangays, the Sama ng Tawi-Tawi acts as the service boat, and thus has an engine. It is the support craft and contains all essential electronics – a satellite phone, GPS, emergency equipment, radios, radar reflectors and other modern navigation components. Unlike the olden days, our seas now support a myriad of vessels. Straits are busy with ship crossings; ports are sometimes congested. Hence, the team needs to be able to communicate with authorities in terms of safety and abide by maritime laws.)

The real challenge in sailing is the weather. Assuming that there is enough food and water, and accepting that human comforts are at a minimum, the force of nature is the number one concern. As seafarers, knowing how to read the weather and sea conditions, knowing when to sail or when not to sail, can spell the difference between safety and disaster.

When I sail with the boats, I gaze out onto the water and see playful dolphins and whales, majestic sunsets and equally glorious sunrises, the full moon rising from one horizon and setting on the opposite side, a sky full of stars…. it all makes me wonder. Our ancestors must have witnessed the same as they gazed upon these waters or looked up to the night sky. Time seems to stand still in those moments.

I first learned about the balangay project seven years ago because the first replica, Diwata ng Lahi, was constructed beside the Cultural Center of the Philippines in Pasay City. As a professional photographer, I was invited as part of a media group. At that time, I already had strong personal interest in heritage and cultural documentation using 360-degree immersive imaging.

For the first voyage, I was invited to sail with the crew throughout the entire journey but had to turn it down due to my regular day job. I contented myself with meeting the crew in different ports whenever I could. The adventure and the many places and extraordinary sights not accorded to a general traveler fueled my passion even more!

I was able to travel the entire stretch of the Southern Philippine islands from Zamboanga to Basilan to Sulu to Tawi-Tawi and ultimately to the homes of our boat builders in Sibutu and Sitangkai in August 2010.

We also visited the island of Simunul, where Islam first began in the Philippines. We paid our respects at the tomb of Rajah Baguinda, summited Bud Bongao, the highest point in Tawi-Tawi and docked in the fabled Turtle Islands.

This year, three balangays again sailed the coasts of the Philippine islands, in an attempt to cross the South China Sea to reach China.

Why China?

2017 marks the 600th year that Sultan Paduka Batara, a Muslim ruler of Sulu, left with his family and 300 followers on a tribute mission to the Ming Imperial Court.

The mission, onboard ships very much like the balangay, was welcomed by the Ming Emperor Yong Le. However, on his way home, the Sultan fell ill and died in Dezhou, Shandong, 320 kilometers south of Beijing.

Upon learning of the tragic news, the Ming Emperor ordered a royal funeral in his honor. The Sultan’s wife and two of his children remained behind in order to tend to his tomb (existing to this day); they were granted lands and eventually, citizenship.

Today, a 3,000-strong clan descended from the Sultan of Sulu continues to live and prosper in the city of Dezhou and around the globe.

Valdez and his crew, including myself, thought to retrace the journey of centuries past as the best way to commemorate this historic saga.

For this historic voyage in 2017, the team was initially set to cross the South China Sea from Manila to Hong Kong during the latter part of May, but due to numerous instances of boat servicing and repairs, the window of crossing had closed with the arrival of the monsoon season.

As the three balangay boats are constructed of old wood, donated by former Sulu governor Abdusakur Tan, using ancient methods, they are not all-weather vessels and thus require fair winds and calm seas to sail.

The distance from Sulu to Manila is already around 1,000 kilometers; add about three more days to sail 600 nautical miles from Hong Kong. With rough seas and big waves, the team simply could not risk the safety of the crew and the boats.

Valdez still desires to make the historic retracing of the voyage in 2018. With the right weather, the team plans to cross the South China Sea in March or April next year and hope to be sailing back home by the middle of May.

The ultimate dream is to travel through the Grand Canal that runs between Beijing and Hangzhou over a total length of 1,794 km. The canal is heavily congested with some inaccessible sections. But we are still hoping that Chinese authorities, seeing the merits of this historical voyage, will permit our boats to be able to navigate in selected sections that will ultimately lead to at least Beijing.

Back home

“A leader’s proudest moment is not what he has achieved, but that he has brought back his crew safely home to be reunited with their families,” said Valdez, our expedition leader, at the conclusion of the first voyage. “Our team is composed of different individuals with different cultures and beliefs, yet we journeyed as one boat, as one people; with tolerance and understanding. This is something that our country needs today. Our archipelagic nature should not be a reason why we cannot come together as a people; the waters are there not to divide, but to unite.”

Rizal, in one of his essays, Philippines: A Century Hence, said: “Perhaps the people will revive their maritime and commercial activities for which the islanders have a natural aptitude, and free once more, like the bird that leaves his cage, like the flower that returns to the open air, they will discover their good old qualities which they are losing little by little and again become lovers of peace, gay, lively, smiling, hospitable and fearless.”

So perhaps it is by looking back and reviving our maritime heritage that we can truly move forward as one nation.

Six hundred years may be a drop of water in the vast ocean of time and memory, but the historical ties that bind our two nations, that cord that continues to connect the people of the Philippines and the people of China, with shared aspirations between our two cultures, will always be there – we only need to look back and sail ahead.