My father grew up in Davao but left in the late 1930s to study in Shanghai. When he returned in 1947, he decided to settle in Manila where he married. My sister and I were both born and raised in Manila.

I was about five when I took my first plane ride, my mother bringing me down to Davao to see my ahma, my paternal grandmother. The summers of my youth were to become my ahma’s with many more visits.

After I graduated from the University of the Philippines in Diliman in Quezon City in 1977, my first job was with the Catholic Church’s Mindanao Secretariat of Social Action, which had its main office in Davao City. This delighted my ahma no end. The work meant I was constantly on the road, off to every corner of Mindanao, but about twice a month I would return to Davao City, drop by the MISSA office and walk about two blocks to Ahma’s home.

My work with MISSA mainly involved meetings with priests and nuns and occasional bishops. Yet, my home in Davao City was a Buddhist Po Lian (Treasured Lotus) temple, where my ahma lived and which she administered for more than 30 years.

The temple is on Quirino Avenue but when I was visiting as a child, I remember the street was called Jacinto Extension. There were few buildings in the area then, and the landmark for taxi drivers was the “Chinese school,” meaning the Davao Central High School. Today, the temple is surrounded by commercial establishments, including a call center, as well as banks and restaurants. The school is still there but for taxi drivers the more familiar landmark is no longer the “Chinese school” but the Gaisano Mall.

As a child, each trip to Davao was a treat, from taking the plane to eating durian, to enjoying ice cream at Merco or going off to Talomo beach or Pearl Farm Beach Resort in Samal.

Sometimes, if my father went with us, he would treat us to a stay at the Davao Insular Hotel, which at that time, with sprawling grounds, seemed like the most luxurious hotel in the world, with Manila’s hotels looking tiny and dingy in comparison.

I have to admit that in my teenage years, I began to dread going to Davao because it just was not as exciting as Manila. The only shopping center was Aldevinco, and I had grown weary of seeing the same batik products over and over again.

And then in my early 20s, I began to read up on Buddhism. Davao and Po Lian Temple took on a new attraction. I grew up boasting that my ahma was a Buddhist nun only to learn later, after I had begun to read up on Buddhism, that she was not quite a nun. Everyone called Ahma a chay ko, literally meaning a vegetarian woman, which was a term used to refer to very devout, but lay, Buddhists. Yet she ran the temple alone, with no monks and superiors.

People streamed in and out of the temple every day and at the end of the day the temple was often shrouded by the fog and smell of incense. The temple had even more people on the first and 15th of each lunar month and on Buddhist holy days, when there would be group chanting of the sutras (prayers), capped by a vegetarian lunch.

Whether on regular or special days, many of the devotees went to the temple with special requests, mainly for businesses to succeed and to be able to bear children, preferably sons. Ahma’s role was to add to the prayers. She would stand next to the supplicants and begin to pray aloud, the prayer more like to a conversation as she would explain the problem and the appeal, almost like a lawyer interceding for a client in court.

Ahma’s “success rate” was said to be quite high, especially for begetting sons. The older Chinese still talk about one couple who already have nine children, all daughters. It was Ahma’s prayers, they say, that brought a 10th child, a son. There’s a sequel to this: twin girls followed, then still another girl, for presumably a happy baker’s dozen.

Ahma also attracted people who needed counsel or, more accurately, needed someone to read oracles in their search for answera to their questions. She told me the most common questions were about potentials and risks for jobs and business, career choices, migrating to the States, and, most importantly, the prospects for bearing a son.

The process was called thieu tsiam, where devotees take a bamboo tube with sticks numbered 1 to 100 and shake the tube until one stick falls out. Ahma would look at the number and go to a cabinet, pull out the drawer with the corresponding number, and bring out a sheet of paper with a short four-line verse, which she would then interpret.

Ahma was really a folk psychologist who listened, comforted and counseled. If she said she would pray, pray she did, often late into the night. For more serious cases, she would go through a particularly rigorous style of supplication involving standing and kneeling and gently hitting one’s head on the floor over and over again, “a hundred times each time,” as when she had to pray for my mother, who became very ill in 1965 and was given six months to live. My mother passed the six-month mark and is still alive today.

There was an ecumenical spirit to it all. Ahma never tried to convert my sister and me, and although she was a strict vegetarian, she had no qualms about serving meat when we visited, for as long as the food was cooked and served separately from her own. Today, my sister and I practice Buddhist meditation and have drifted to vegetarianism.

Despite the ecumenical spirit, however, Ahma was fiercely loyal to Buddhism. Once in her 70s, she had to be confined in the hospital and the hospital chaplain approached her. Her story to me was that he tried to convert her and she had reacted with mild anger. How, she asked, could this priest expect her to give up the faith she had held for so many years?

I smiled when she mentioned this because, in fact, local Chinese had become notorious for religious syncretism. Even in Ahma’s time, many of those who dropped by the temple – my sister and I included – were actually baptized Catholics.

There was no contradiction between going to the temple and then moving on to a Catholic church for mass, or to a Taoist temple for advice on feng shui (geomancy) or to communicate with the dearly departed.

It was only recently that I began to appreciate still another aspect of Ahma’s life. After I wrote about Ahma in my Inquirer column, I received a letter from Fr. Ari Dy, a Jesuit.

He was researching on Chinese Buddhism in the Philippines and said that chay ko like my ahma had played a pivotal role in keeping alive certain religious traditions from southern Fujian in China, the region that is home to the ancestors of many ethnic Chinese in the Philippines.

These included the very tradition of the chay ko, where lay women could end up running a temple, the use of the thieu tsiam, and the special devotions to Guan Yin or the Goddess of Mercy.

What was so phenomenal about Ahma was not so much her one-woman management of the temple as the way she had come to that vocation in a colorful life whose details I put together mostly from her own stories. These stories were often told with a sense of urgency as she would insist that she was about to “reach time” (kao si in Minnan Chinese), meaning she was old and about to die. The details remained remarkably consistent even in her very old age.

I dug up other information on her from older ethnic Chinese in Davao and from a visit to our ancestral village in Fujian, where I got to read our ancestral books – records listing the dates of births and deaths of our clan – including those of my paternal grandfather and his wives and children.

Lotus feet

Ahma was born in 1893. Her most graphic memories of childhood was about how, as a very young child, her own mother used strips of cloth to bind her feet in the pak kha (foot-binding) tradition, as did other Chinese mothers for about a thousand years.

Her feet were bound so tight that each night, she would beg her mother to have the bindings removed. Her mother would scold her, “Don’t be silly,” she would say, “you will never be able to get married with big feet.”

What did a little girl know about marriage, my ahma would rhetorically ask, but that was the fate of Chinese girls, their feet kept tiny, crippling them for life. I have to say though that despite those tiny lotus feet as they were called, she was always on the go. My visits, especially when I would arrive, and then had to depart, often involved chasing after her because she was always so frantic and I was always worried she would fall.

Little Chinese girls in Ahma’s time did not go to school either, so she grew up illiterate.

And there is no record of when she was married. My grandfather immigrated to the Philippines early in the 20th century and had married a Filipina, Clara Divino, who died young at childbirth. I figured my ahma came to the Philippines much later, given that her eldest child was not born until 1919.

She took in the orphans left behind by the Filipina wife, and in 1928, when she was herself widowed, she was left to raise all seven children, the four from the Filipina (Bienvenido, Antonia, Esperanza and Narciso) and three more of her won (Jose, my father Julio and Pilar). A court eventually ordered that the two mestiza daughters be raised by relatives on their biological mother’s side, but the two mestizo boys cried their hearts out when their Filipino relatives came to take them as they had grown so attached to their Chinese guardians – my ahma and the Chinese families who had helped them out.

They then ended up with Ahma and eventually were allowed to stay with the Chinese woman with bound feet. (One other mestiza daughter had been brought to China quite early, and never returned to the Philippines.)

Tita Panching (Esperanza) married a Davaoeño, Manuel Generoso Cabaguio, whose family produced a biography, If He Were Here Today, in 2007. The book provides additional information about my ahma and her relationship with her stepchildren.

I never forgot my ahma’s stories about how she would breastfeed her own biological son Jose, together with Narciso, the youngest of the mestizo children, one on each breast she claimed. The only times I saw her eyes mist up were when she would talk about this adopted mestizo son, who died after a dental extraction at 18.

Family folklore claimed he had bled to death and so for years, we would fret whenever a relative had to have a dental extraction, thinking hemophilia might run in the family.

My father always insisted on a blood-clotting test before a dental procedure. The tests always yielded normal results. It seems that the royal pretensions (hemophilia being commonly found in the royal families of Europe) had no basis. I suspect now that Tito Narciso had died of an infection acquired during the extraction.

Sometimes in the 1980s, we transferred the remains of my paternal grandfather and Tito Narciso to a new grave. I was working with public health programs at the time and, at the cemetery, I thought about how these early deaths were stark reminders of how difficult life must have been in their time, in Davao, with the lack of access to proper medical (and dental) care claiming many young lives. Sadly, even in the 1970s and on into the 21st century when I worked in Mindanao, I continued to see this neglect of health needs.

The Chinese community in Davao is probably of fairly recent origin, meaning the 20th century. Earlier waves of Chinese had concentrated in Manila and other larger cities. Davao and Mindanao were frontier areas. Over time, however, they did attract Chinese. From my father’s stories, life in Davao in those times was dangerous as well, with many early Chinese immigrants losing their lives to bandits.

I still remember how simple the homes were for the Chinese, especially in the 1960s. But with each visit I could see, too, how they were growing prosperous, even as many continued to be quite thrifty. Many moved to Manila, and still others immigrated to the West.

Life was particularly hard for Ahma as a widow. But she survived with some financial support from her brothers and doing odd jobs, mainly mending clothes, and at one point, even becoming a midwife.

Ahma’s religious life mirrored the social life of the Chinese community. For many years, before the temple was built, she lived in a small wooden house in Uyanguren, where she put up a small altar in her home, with one Buddha, for her own personal devotions.

But people would ask if they too could pray with her and seek counsel and, soon enough, Davao’s Chinese community raised the money to buy land and then build her the Po Lian Temple. The foundations were laid in 1959 and Ahma devoted the rest of her life to the temple. She had received no formal training in religious studies, but did get advice from other chay ko.

There was Sim Lian Ko from the Che Wan Temple in Manila, and Siu Yin Ko, who founded the Po Chong Temple in Cubao in Quezon City. It was only through Father Ari that I learned how important these chay ko were in the lives of local Chinese Buddhists, an extraordinary instance of women carving out their niche in a male-dominated society.

Tina Chua, daughter of Ngo Siu Kan, one of Ahma’s closest friends and a neighbor in Uyanguren, tells me that many of the Chinese immigrants, the women especially, were illiterate and had to rely on the younger ones to read the prayers. Tina herself often had to read the prayers on behalf of her parents.

My ahma was determined to go a step further. In her 50s, she learned to read Chinese so she could lead with prayers, and do the thieu tsiam oracles. That was quite a feat considering how difficult Chinese is, with thousands of characters to memorize. She never learned to write in Chinese but could manage her name: her surname Lin and ping, the word for peace.

Ahma had a way of bringing people back to the temple, each with their own equivalent of the Christian panata or vow. Tina says my ahma would tell devotees not to donate money if they were hard up, and to instead help out with the cooking at the temple or by washing dishes.

That was what Tina’s mother did, and Tina is convinced that is what generated all the hok or good fortune for the devotees and the Chinese community. Now based in Manila, Tina still flies to Davao three times a year for special Buddhist holy days to visit Po Lian.

Reaching time

One night in September 1990, as I was preparing to leave for a conference in Germany, I got a phone call from Davao. Ahma was in the hospital with pneumonia and had slipped into a coma. I conferred with my father, rushed down to Davao, and met with the doctors.

The prognosis was not good, but no one could tell, too, how long she would last. I lingered, then finally said goodbye, whispering in her ear that she did not need to worry about us and that she could go. I returned to Manila and went on to the German conference with a heavy heart. My mother flew down to Davao for the death watch.

Almost two weeks later, on Sept. 30, I returned to Manila and shortly after getting home, my mother called in from Davao to tell me, “Ahma’s reaching time.” Ahma did reach time about half an hour later, she was 97.

My visits to the temple dwindled. Several times I would have conferences in Davao City but avoided dropping by the temple. With Ahma gone, I felt there was no reason to visit.

But in October 2010, shortly after the 20th anniversary of Ahma’s death, I had to attend a medical conference in Davao City.

At the close of the conference, on the morning of my scheduled departure, I looked out the window of my hotel and, seeing the bay, and the horizon, I was overwhelmed by nostalgia.

I dropped by the temple, now in the care of my Uncle Jose and Auntie Pinhua, and was told there were still devotees coming in, many from among the sin kiao or new Chinese immigrants from the mainland. There were new, but their concerns were similar to those that Ahma used to handle: success in business and in having sons.

During that visit, I met, for the first time, a one-year-old girl named RC, daughter of my youngest cousin Charlie, and his wife Rhea. As I took RC into my arms, I knew I would have to come and visit again.

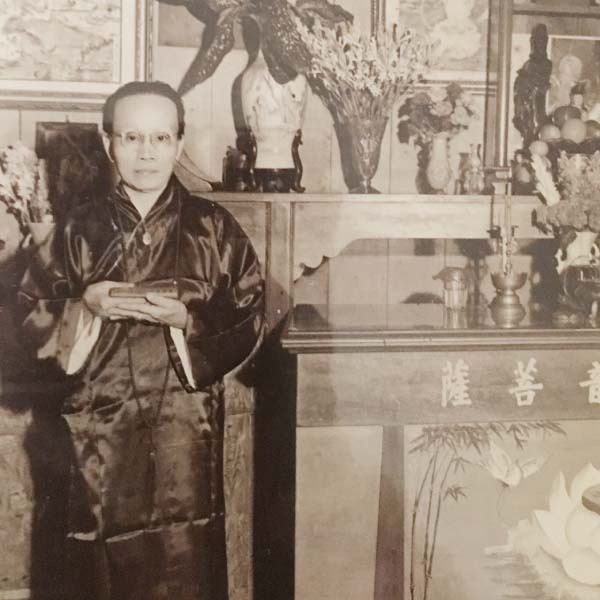

Two months later, I brought my family to Davao. There was palpable excitement for everyone, especially my kids – all toddlers – who were totally enchanted by the temple. At the side of the temple was a small memorial hall built in honor of my grandmother, with her photograph at the center. My ever-curious son called out to his sisters to come in and look at “Ahma,” insisting maybe she was buried somewhere in the hall.

The entire family posed in front of her photograph and as the camera shutters clicked away, I knew I would be visiting Davao many more times, together with my family.

I thought about what I had learned from Ahma about quiet strength, about respect for other people’s religious beliefs, about endurance, persistence and generosity. She was not unique, certainly, and I know many Filipinas are now in her position, trying to survive and raise families in strange new lands while carrying on the culture of the homeland.

Having prayed for so many people to have children, Ahma faced the dilemma of her own favorite grandson refusing to marry and have children. This was where she did nag, more persistently as she aged, and I will admit it did, at one point, keep me from visiting her more often.

In the end, Ahma, as usual, did get her way with me, four times over, although in rather unorthodox ways. I remain unmarried, at least in the legal sense of the word, but I did follow Ahma’s footsteps, taking in children not my own but loving them as she did my Tito Narciso.

Before leaving for the airport, I rushed back to the memorial hall and waved at Ahma, “I’ll be back.” On the way to the airport, I thought, maybe someday, I – or my children – will talk about going home to Davao.