Each Chinatown around the world has a unique flavor of its own, coming from how the local Chinese community blends its culture and traditions with those of the host nation.

A good example of this is Bangkok’s Chinatown in the Samphanthawong district. I rediscovered Bangkok’s Chinatown on a recent trip to Thailand.

I convinced my travel companion Miko to join me, offering to treat him to breakfast at Chinatown. So we left the hotel at 7 a.m. with visions of warm dumplings and buns.

As our Thai Uber driver wove in and out of the early morning traffic, I began telling Miko about how Bangkok’s Chinatown got started.

In 1782, Thai king Rama I decided to move the capital from the north down to Bangkok. However, the land that he wanted for his royal residences was occupied by a Chinese settlement. So, the Chinese moved out to an area two kilometers to the south where a temple called Wat Sempang was located.

King Rama I’s royal residences later became the famous Grand Palaces, while Bangkok’s Chinatown grew to become one of the biggest Chinese settlements outside China.

Our driver dropped us off not far from Sempang Lane. Since comparison with Manila’s Chinatown will be inevitable, Sempang Lane reminded me a bit of Carvajal or Tabora and Ylaya streets in Binondo.

The main difference is that parts of Sempang Lane are longer and most of it is covered with a polycarbonate roof. Many of the shops here are wholesalers and offer the same goods one finds inside the 168 Malls, like beauty accessories, toys, bags and stationeries.

Sempang Lane today is a busy commercial zone. During the 1870s, it was a notorious red light district. Brothels and gambling dens lined the street. There were so many brothels here that the term “Ae Sempang” became a slang word for a prostitute. It was not until the early 1900s when the Thai government began to crack down on the illegal activities here.

Apart from the shops, the street was alive with food carts and stalls serving breakfast. We walked past at least three or four temples and shrines. They seem to belong to minor deities and gods as I could not find the names of the temples in guide books or online travel maps.

Like Divisoria, many of the shops close at around 6 p.m. but unlike Divisoria, there is no night market here. So if you plan to visit Bangkok’s Chinatown at night, stay on the main road which is Yaowarat where most of the crowds are.

Yaowarat is the main strip of Bangkok’s Chinatown. Before the Chinese community resettled here in the 1780s, it was nothing more than a dirt road. Since then it has emerged as the commercial center for Bangkok’s Chinatown not unlike Ongpin Street. In fact, Yaowarat is synonymous to Bangkok’s Chinatown.

Like Ongpin, Yaowarat is known for its food. Many of the online tours focus on the many available food specialties such as grilled prawns and guay jab (noodles in peppery soup).

In some ways, the Yaowarat food scene is a bit different from that of Binondo. One can find bars and drinking establishments here that offer wines and cocktails. Of course, these cater more to Western tourists rather than locals.

Based on the style of architecture common along Yaowarat, the last time this street had a building boom was between the 1950s and the 1960s.

According to one guide, Bangkok’s Chinatown at that time was the business and entertainment hub of the city.

In fact, three of the country’s tallest buildings then were located here. While some of the buildings are still in use, others appear to be waiting for new owners.

Upon reaching Yaowarat, I turned right and kept walking straight to reach the Chinatown Gate. Along the way we noticed that like Ongpin there were a lot of jewelry stores.

Probably like their Tsinoy counterparts, the Chinese-Thai view gold as an important investment.

We saw one of the bigger ones, the So Seng Heng Jewelry Store, at the intersection of Yaowarat and Thanon Phadungdag road. It was said to be the biggest jewelry store in the area with six floors of retail space and a workshop.

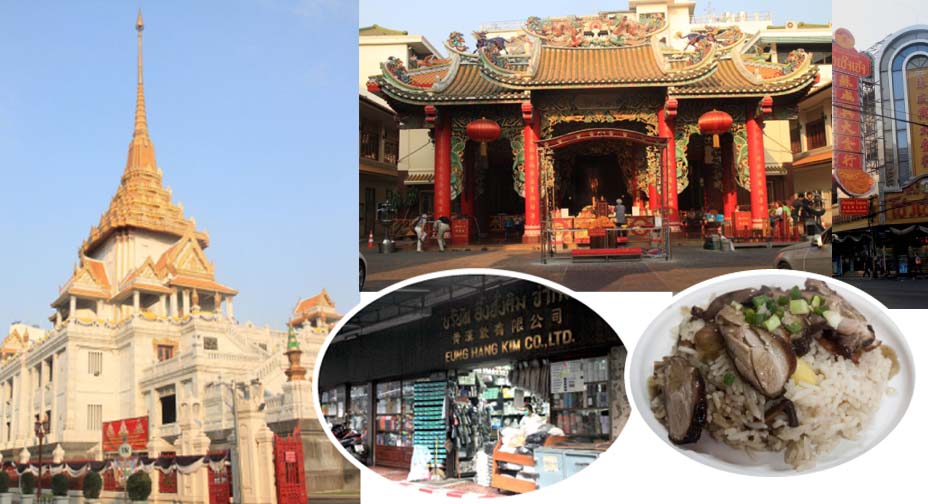

Keeping a steady course toward the Chinatown Gate, we made a stop at one of the area’s major temples, the Kwan Yin Shrine, located on the grounds of the Tien Fa Charity Foundation Hospital.

Despite its traditional appearance, the temple is fairly new as it was only built in 1983. But the solid teak wood statue of the Kwan Yin (Buddhist Goddess of Mercy) inside the temple is said to date back to 1200 AD and was given to the hospital in 1958.

A short walk from the Kwan Yin Shrine is the Chinatown Gate, the official entry point to Bangkok’s Chinatown. It is also known as the Odeon Gate, in reference to a movie house that once stood nearby.

The ornate red and gold gate was set up in 1999 to commemorate the late King Bhumibol’s 72nd birthday. The calligraphy on top of the gate, “Long Live the King,” was done by the king’s daughter, Princess Maha, who is said to be fluent in putonghua.

In fact, the current Thai royal family is said to be descended from a mixed marriage between a Chinese man and a Thai woman.

Like the Tsinoys, many of Thai’s most prominent politicians, businesspeople, actors and singers boast of mixed Thai-Chinese heritage.

But this did not mean that the local Chinese community was free from discrimination.

Between the 1930s to the 1950s, the government tried to control the Chinese business community through new taxes and regulations.

In 1932, they made Thai the compulsory language for education. Protest from the Chinese community led to the law being amended to allow for two hours per week of Mandarin language education.

From the Chinatown Gate, it was short walk to the Wat Traimit or the Temple of the Golden Buddha. The 15-foot tall gold Buddha statue was supposedly made between 1200 and 1400.

When the Burmese army ransacked Thailand, the monks must have covered it in plaster to protect it from being stolen. It was not until 1955 that its golden surface was revealed when workmen were trying to move it and a piece of the plaster fell off.

To commemorate the late King Bhumibol’s 80th birthday, a new $600-million pavilion or mondop was built to house the statue, which opened in 2010.

On the second floor was the Yaowarat Chinatown Heritage Center, Bangkok’s version of our Bahay Tsinoy. But unfortunately, it was Monday and the museum was closed for its regular maintenance. At least now I have another good reason to return to Bangkok.

Across the temple, I spotted a food stall and some tables on the street. It was selling lugaw (congee) for only 60 baht (around P86).

In a strange mix of Thai, Putonghua and English, we managed to get two bowls of lugaw with century eggs, meat balls and bitsu-bitsu. With the first sip, we knew we made the right choice to have breakfast in Chinatown.

Since it was still early, we still had time to explore a bit more of Bangkok’s Chinatown. Just a few doors down from the Wat Traimit, we found a small shop space that was once probably a general store or a hardware store.

The original wood and glass cabinetry were still there. But now it is a small restaurant offering sliced smoked duck breast served with either noodles or rice. It didn’t appear on any online guides, but there was a small page from a Japanese guide book recommending it.

I ordered one duck breast and rice plate for us to share. All I can remember after the first taste of the duck meat was that it was tender with a sweet and salty flavor. It affected my memory so much that I nearly left without paying for the food.

On the flight back to Manila, I began to contemplate how the Chinatowns of Manila and Bangkok seem to have many things in common. But what makes them different is how the Chinese-Thai community managed to assimilate into Thai society mainly through intermarriage and religion.

But the older generation Chinese-Thais see the assimilation as a mixed blessing.

Somchai Kwantongpanich, one of the organizers behind the heritage center, expressed this in an online interview. While they feel that it is great that they are now accepted by Thai society, the trade-off is the gradual erosion of their Chinese roots.

This is one of the reasons why they see the need for the heritage center at the Wat Traimit – that it can remind future generations of the legacy of their ancestors.

Hopefully their efforts will succeed and then maybe the unique flavor of this Chinatown can be preserved for future generations.