Not many people know that Iloilo was once the textile capital of the Philippines, and that the Iloilo Chinese Textile Dealers Association, organized in 1880, was the first Chinese textile dealers’ association in the Philippines. It was formed five years earlier than the one in Manila, which was organized in 1885.

What made Iloilo the textile capital of the Philippines and what made the Chinese in Iloilo develop the textile business earlier than their counterparts in Manila? This historical puzzle was answered in a well-researched paper using primary archival materials titled: “The Textile Trade in an Anglo-Chinese City Flying a Spanish Flag.”

The paper was presented by Randy M. Madrid, PhD, university research associate II of the Center for West Visayas Studies at the University of the Philippines Visayas in Iloilo City, at the annual Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day conference held on June 30, 2015.

The paper was included in the volume Reexamining the History of Philippine-Spanish Relations, Selected papers, Philippines-Spanish Friendship Day conference, (2013-2015) published by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines in 2016.

Madrid’s paper examined the nature of the intra- and inter-island textile trade prior to the 19th century that ultimately spurred rapid urbanization of the port city of Iloilo in the Visayas. The more robust exchange of material goods with the opening of the port likewise brought in new knowledge and ideas, strongly influenced by cultural encounters between British and Chinese merchants, Spanish colonial officials and the native population.

Economic enclaves, formed in areas where many Chinese settled and dealt with textile export and import, influenced the history of the rise and fall of the Chinese textile business in Iloilo.

The paper also provided a fine scientific case analysis and study of the role the Chinese traders played in the textile industry in Iloilo in particular, as well as in the colonial economy in general.

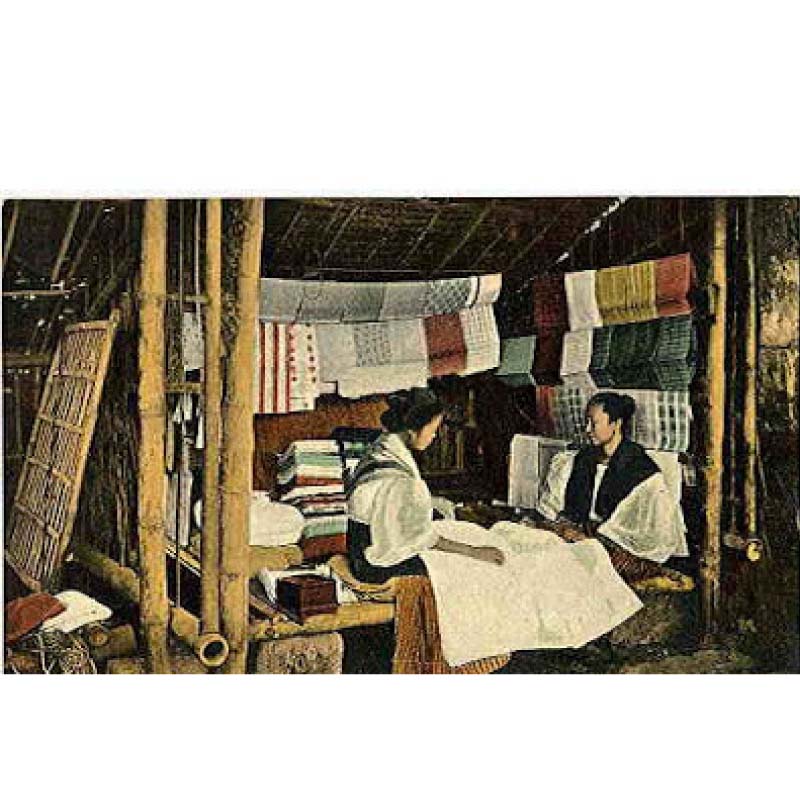

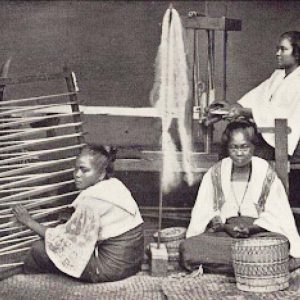

At the height of textile production in 1850, one-half of the province’s labor force worked in the textile industry and there were as many as 60,000 looms operating in Iloilo City and in nearby towns like Oton and Miag-ao.

Madrid quoted the study of famous French traveler Jean Baptiste Mallat, who praised the city for its unique woven products.

Mallat was a member of the French Geographical Society who visited Iloilo in 1846.

He was the first foreigner to make a comprehensive survey of native textiles in the Philippines. He found 10 different mixtures of cotton, pineapple, silk and hemp fiber woven in Iloilo among 52 varieties of textiles he identified in the country. He also recorded a total of 248,000 francs worth of cloth exported from Iloilo to Manila in 1842.

I quote extensively from the paper (pp. 171-200 of the book) in sharing information which was not previously known to many of us.

The beginning of textile industry

Governor-general Jose Basco, who became governor in 1778, was credited with spurring the production of cash crops for export and opening up of hitherto unexplored areas in the Philippines for agricultural production through his General Economic Plan issued in 1779. He relied on the versatility and industrial capability of the Chinese to fully implement his plan.

The development of the textile industry of Iloilo was attributed to Basco’s incentives and encouragement of those who established factories for the production of silk, hemp, linen and cotton. His policy on textile promotion received a positive response among Chinese traders in Iloilo, who became involved in the textile industry and trade.

The colony used to rely extensively on woven products from China to supply the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade. Thus, the Royal Economic Society offered a prize to those who could weave blankets domestically and at the same time imposed a surtax on traders who imported Chinese blankets, including silk cloth.

Thus, from 1824 to 1839, the entry of Chinese blankets, previously in overwhelming quantities, gradually declined.

There was also an appreciable increase in the value of Philippine textile exports: P54,706 in 1818, P72,649 in 1846 and P108,901 in 1856. In 1844, the export of local textiles from Iloilo amounted to P22,791.

This economic success was attributed to the policy of the Spanish colonial government in restricting the entry of imported textile and the combined labor force of Filipinos and Chinese who supervised loom operation.

To counteract colonial restrictions, Chinese textile importing houses formed cabecilla associations to present a united front in bargaining with European importers and assume the distribution of textiles and other goods to all Chinese wholesalers in the city. At the height of the textile boom, the Chinese in Iloilo, through the cabecillas, had the upper hand in the export-import trade.

The development of shipping facilitated trading activities by easing transportation and communication. By 1850, Manila was opened to world trade and in 1855, the port of Iloilo opened to international commerce and shipping. This gave the textile trade greater importance and, consequently, increased Chinese influence in Iloilo, especially in the town of Molo.

Ironically, the opening up of Iloilo port also brought about the textile industry’s ultimate demise, when British enterprises imported British cloth (an essential product of the British industrial revolution) in huge quantities. This was done on instigation of British vice consul in Iloilo Nicolas Loney, who at the same time promoted the shift to sugar manufacturing and export.

By 1855, Iloilo fabrics accounted for $400,000 of the province’s total exports of $720,300. In 1861, the figure reached $1 million. Around 96,836 meters of handwoven fabrics were exported in 1862, increasing to 141,420 meters in 1863.

Decline of textile industry

Loney noted that the textile trade was run by Chinese capital and the weaving factories were, in fact, constructed at the heart of Chinese enclaves in Jaro and Molo.

Since Loney could not penetrate the textile market, he engineered a strategy to take it down.

Loney started by employing the Chinese themselves, together with his new allies, the Chinese mestizos, in the sugar enterprise, which he was most interested in.

He introduced modern mechanized sugar cane presses which revolutionized and replaced the traditional Chinese method of carabao-operated sugarcane presses.

Loney was a British businessman from Plymouth, United Kingdom. His Singapore-based company, Kerr & Co., a merchant house, sent him to the Philippines as it was opened to international trade.

While in Manila, he became a popular figure among the business community. When Iloilo City was opened to international trade in 1855, he was appointed as the first British Vice Consul in Iloilo the following year in 1856.

Madrid describes Loney’s bold ventures:

Loney observed that the Chinese merchants of Molo and Jaro, before returning home after collecting payments for the shipment of fabrics to Manila, purchased raw materials from Chinese suppliers since Iloilo weavers were required to produce 300 tons of fibers annually. These merchants also bought cheap British-manufactured cloth from Chinese shopkeepers in Manila.

Since these Iloilo Chinese merchants got their principal profit from the native textiles, the British fabrics were sold at a very low mark-up in Iloilo and thus enjoyed a growing market, especially among Iloilo’s labor population. By the 1860s, British textile imports to Iloilo were valued at $360,000 to $480,000 a year.

Raw sugar was in great demand and Loney embarked on the export of sugar to Scottish refineries. The return cargo was filled with huge amounts of Manchester cloth from Liverpool, which flooded the Iloilo market since direct commercial shipping from Iloilo to Melbourne and Melbourne to Glasgow commenced in early 1860s.

This drastically affected the export of native textiles, which fell during the 1860s to1890s due to a more than nine-fold increase in British cotton imports as well as the entry of Spanish cotton textile imports to the Philippines from 1883-1893. By 1892, Iloilo cotton cloth imports reached P1,713,392.

The Chinese traders in Iloilo gradually lost their fortune in the dwindling native textile exporting business and shifted to sugar and hemp. Despite provincial Chinese efforts to revive native textile manufacturing, it never regained its former status as one of the prime exports of the province and instead dwindled into a minor commodity supplying domestic demands.

The Iloilo port and its environs were transformed into a British enclave, especially for the growing sugar trade and import of Manchester cloth. With the Chinese out of the port, the former Chinese quarters in the manufacturing of native textiles like Molo and Jaro were reduced to forlorn towns inhabited by a few Chinese textile importers who resorted to ambulant vending in nearby localities.

Madrid’s account showed clearly that the rise of the Chinese textile business in Iloilo was the result of the Spanish colonial policy at that time to encourage and stimulate the local textile industry and at the same time restrict and discourage importation of Chinese blankets and cloth.

On the other hand, the demise of the Chinese textile business in Iloilo was caused mainly by the massive importation of cheap British cotton cloth that the Chinese textile traders were unable to compete with.

It is a clear indication that the British capitalist economic power after its industrial revolution was far beyond the Chinese merchants in Iloilo as well as in the Philippines to compete or fight with.

This clearly showed that domestic policies and/or local conditions hold greater sway in the success and decline of Chinese businesses. Thus, we should realize the true factors behind the role and the actual economic strength of the Chinese in Iloilo and the Philippine colonial economy rather than their bloated and over exaggerated mythical or innate “business acumen.”

Prominent Chinese in Iloilo textile business

Madrid’s paper shared a lot of precious information and material on the prominent Chinese in Iloilo’s textile business.

Foremost among them was Francisco Manzano Yap-tico (葉池戈). Born in Xiamen (Amoy), baptized as Catholic in Iloilo in the 1840s, he established a general export-import house in Iloilo with branches in Manila and Cebu.

Specializing in textiles with combined commission agency and hemp and sugar exporting firms, he was assisted by his son Yap Seng (葉開陞) in Iloilo and grandson Yap Tian Sang (葉天送) in Manila.

He also assumed agencies of western and Chinese insurance companies, owned inter-island vessels and ran a foreign exchange department that dealt with remittance and loans.

With the dissolution of the cabecilla system in 1887, Yap-Tico was appointed one of the tieniente primeros (principal leaders) of the 12-member Gremio de Chinos in 1891-1893.

For the next two decades, due to his strong commodity trading business supported by shipping and financial services, Yap-tico was a man to reckon with in the business environment of Iloilo and the country.

Yap-tico likewise helped organize the Iloilo Chinese Textile Dealers Association in 1880 with Marcelino Tan Dico, Fernando Yap-piengco, Alfonso Lim Ponco and Tan Chanco. They maintained large warehouses and sari-sari stores for storage and display of hilados y tejidos (dry goods).

Most importantly, while the British traders were content in their control of the port and their Chinese mestizo allies in their manorial estates in Negros, the Chinese businessmen wanted desperately to have the upper hand in the city’s retail trade.

Pushed to the heartland located at the southern bank of Iloilo River, they eventually found themselves occupying the most suitable space for trade and commercial ventures.

This gave birth to Calle Real, the city’s main thoroughfare that was transformed overnight into a Chinese enclave.

To this date, ever busy and bustling Calle Real remains the heartland of the Iloilo Tsinoy community.