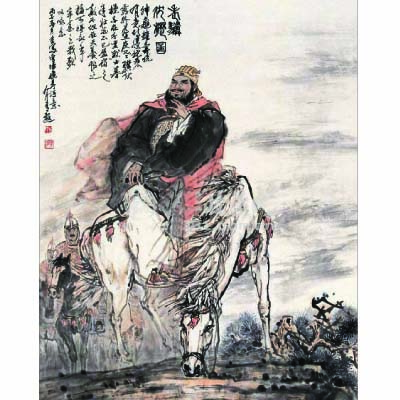

Few ancient Chinese rulers are worthy of the title of poet or man of letters. Yet Emperor Wu Du of Wei, Cao Cao by name, who was an outstanding statesman and strategist, was a distinguished poet as well.

Su Shi, a famous man of letters in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), admired him so much that he called him a hero who “composed poetry with lance in hand.”

Cao Cao, whose literary name was Mengde and nickname Aman, was born to a powerful court official’s family in Boxian county, Anhui province.

As a child, he grew very fond of poetry, history and books on the art of war. And through constant practice on horseback and in archery, he excelled in martial arts.

At the age of 20, Cao Cao held the official position of Beibuwei in charge of public order in the capital, Luoyang.

On his first day at work, he bade some artisans to make a dozen colored sticks to be hung at both sides of the official mansion, and issued an order that “anyone who violates the law shall be beaten with these sticks.”

One evening while he was doing the rounds in town, he found the uncle of one of the court officials bullying some civilians. Without a moment’s hesitation, Cao Cao ordered that he be beaten to death in accordance with the law.

From then on, nobody dared violate the law in the area governed by Cao Cao. Order in the city was never this good, and Cao Cao’s name became known to all.

During the last years of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), Emperor Xian Di of Han was obliged to leave Chang’an and take refuge at Luoyang, owing to the fighting among powerful military commanders.

Cao Cao was relatively weak in military terms at that time, but he was shrewd enough to take advantage of the opportunity to invite the emperor to come to Xuchang, which was his domain. Naturally, the town became the provisional capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Then, Cao Cao began issuing orders in the name of Emperor Xian Di of Han, and gradually expanded his own military strength and sphere of influence.

By cutting taxes and launching water conservation projects, Cao Cao encouraged the peasants to increase production and successfully solved the problem of food supply.

His power grew in unifying north China and establishing his own regime, the Kingdom of Wei.

Cao Cao showed extraordinary talent in various fields, such as administration, diplomacy and military affairs. The Art of Warfare by Sunzi, which he annotated personally, was his constant companion.

In the famous battle at Guandu, Cao Cao defeated, with combined courage and wisdom, Yuan Shao’s army of 200,000 with a force of about 30,000 to 40,000 men under his command, creating in the annals of Chinese warfare a miracle of defeating an enemy numerically far superior and apparently more powerful.

It happened that Cao Cao was once riding at the head of his troops along a narrow path in some wheat fields and, beholding the luxuriant growth on both sides, gave orders that no one should be allowed to trample on the wheat and that anyone who disobeyed should be beheaded.

At this, the soldiers all dismounted and started marching on foot. Presently Cao Cao’s own horse bolted and rushed into the wheat fields.

In those days, laws were never applied to a sovereign, but Cao Cao said to his officers and men, “How can I expect my troops to follow me if I myself violate the military laws I made. But I am the commander-in-chief. Without me the army would be leaderless. So it behooves me to mete out my own punishment.”

With these words, Cao Cao drew his sword and cut off his head-dress in place of his head. Then he had it hung by the side of the path as a warning to all.

Once when Cao Cao was to receive an envoy from the Huns, he had some misgivings that his short stature and rather plain features would cause the Huns to despise the State of Wei.

So he had a handsome-looking minister with a long beard and a deep resounding voice sit on the throne in his place, while he himself stood by the side of the “emperor” with a broad sword in hand.

After the reception, Cao Cao secretly sent someone to ask the Hun envoy, “What do you think of the King of Wei?”

The envoy replied, “He looks distinguished indeed, but the man who stood beside him seems to be a true hero!”

Cao Cao lived in an age of war and chaos. Amidst all the tensions and hardships of a military life, he managed to write many great poems and essays in which he expressed his lofty aspirations to accomplish great military exploits and deeds.

Once when he was 53 years old, Cao Cao came to Mount Jieshi with his army after a successful military operation. Confronted with towering mountains and boundless seas, he felt a great surge of emotion and felt impelled to give voice to his poetic feelings.

The result was the impromptu “Long-lived Tortoise,” a poem of four-word lines, in which he wrote: Since ancient times, the tortoise which was believed to enjoy a longevity of thousands of years would still perish; short as the life of man is, he should not allow it to be wasted, but ought to lengthen it through unremitting efforts. He then compared himself to an aging horse that was still yearning to make a long journey, although it was for the moment resting tranquilly in the stable.

In this poem, Cao Cao expressed his ardent desire and determination to continue his struggles in old age. In some of his other poems, he revealed the misery of the people caused by ceaseless fighting among powerful military commanders. All of them are of great ideological and esthetical value.

Cao Cao’s literary talent had a profound influence on his two sons Cao Zhi and Cao Pi. The three together, referred to as the “three Caos,” were the standard bearers of literary creation in what is called the Jianan Period in Chinese literary history. Their literary activities occupy an important place in the history of the development of Chinese poetry.

横槊賦詩

中國古代帝王中,真正稱得上詩人或者文學家的很少。魏武帝曹操不僅是一位出色的政治家、軍事家,而且是一位著名的詩人。宋朝文學家蘇軾讃賞他是一位“横塑賦詩”的英雄。

曹操,字孟德,小名阿瞞,安徽亳縣人,出生在一個有權有勢的大宦官家庭。他從小喜歡讀詩、讀歴史、讀兵書,學習騎馬射箭,練出了一身真本領。

曹操二十歳的時候,擔任了國都洛陽的北部尉,負責治安。開始工作的第一天,他就命令工匠做了十幾根五色大棒,掛在官府大門的兩邊,並宣布了命令:“不管誰違反了禁令,一律用棒打。”

一天晚上,他親自查夜,發現皇帝寵愛的一個宦官的叔父正在欺負百姓,曹操堅決按照禁令,命令用棒打死。從此以後,没有人再敢在曹操管轄的地區違反禁令了。城裡比以前安定多了,曹操也出了名。

東漢末年,軍閥混戰,漢獻帝只好從長安逃到洛陽避難。當時,曹操的勢力還很小,他看凖了時機,把漢獻帝迎到自己的駐地許昌,許昌自然成了漢王朝的臨時國都。

曹操就借用漢獻帝的名義,發布命令,漸漸擴大了自己的勢力。曹操還減輕賦税,興修水利,鼓勵農民發展生產,解決了糧食問題,實力越來越雄厚,逐漸統一了中國北方,建立了曹操政權。

曹操在内政、外交、軍事等各方面,表現出了非凡的才能。他經常研究《孫子兵法》,還親自給這本書作注釋。

在著名的“官渡之戰”中,曹操有勇有謀,用僅有的三、四萬兵力,打敗了袁紹的二十萬大軍,創造了中國戰爭史上以少勝多、以弱勝強的奇跡。

有一次,曹操帶領隊伍經過一條小路,看到田裡的麥子長得很好,就下令:不准踩壞麥田,違反的人一律殺頭。士兵都下馬步行。這時候,曹操的馬卻突然受驚,跑到麥田裡去了。

那時候,帝王犯法無罪。可是,曹操對執行命令的將士說:“我自己制定了軍法,卻先違反了,今後怎麽帶兵打仗?但我又是軍隊的統帥,如果砍了頭,軍隊就没有統帥了。這樣吧,請讓我對自己用刑。”說完,就拔出劍來,割下自己的頭髮來代替殺頭,並把頭髮掛在路邊示衆。

又一次,曹操要接見匈奴派來的使者,他覺得自己身材矮小,相貌不美,怕匈奴看不起魏國。於是,就讓一個鬍子長長、聲音響亮、相貌英俊的大臣代替自己坐在皇帝的寶座上,自己則握著大刀,站在“皇帝”的身邊。

事後,曹操暗中派人去問匈奴使者:“你覺得魏王怎麽樣?”使者問答說:“魏王相貌不凡,不過在他身邊的那個人,才像真正的英雄啊!”

曹操生活在戰亂的年代,在緊張和艱苦的軍旅生活中,他寫下了許多氣勢雄偉的詩歌和文章,抒發他建功立業的雄心壯志。

曹操五十三歳那年,在一次戰鬥勝利後的行軍途中,帶著隊伍來到碣石山。他面對高山大海,手握長矛,感情起伏,詩興大發,吟誦了一首四言詩《龜雖壽》。

詩中寫道:自古以來,能活千年萬年的烏龜,終有一死;人生當然有盡頭,但是不應該隨便結束自己的一生,應該不斷努力,去延長自己的壽命。

接著又把自己比作一匹老馬,雖然伏卧在馬棚裡,卻仍然有著行走千里的壯志。詩歌表達了他晚年繼續奮鬥的信心和決心。

曹操其他的詩歌還揭露了軍閥混戰給人民帶來的苦難,有很高的思想性和藝術性。

曹操的文學才華,深深地影響了他的兒子曹植和曹丕。父子三人是中國建安時代文學創造的主將,被稱作“三曹”。他們的文學活動,在中國詩歌發展史上佔有重要的地位。