People assume that you need loads of cash to set up a proper history museum filled with an extensive collection of artifacts and antiques. Wilven Infante, a 49-year-old school teacher at the Pedro Guevara Elementary School on San Fernando Street in the San Nicolas district in Manila, is one person who disproves that assumption. Pedro Guevara Elementary School sits on top of what used to be the eighth parian, the Alcaiceria de San Fernando. Built in 1762, it was intended to be a place where traders from China would come to do business and pay their customs duties.

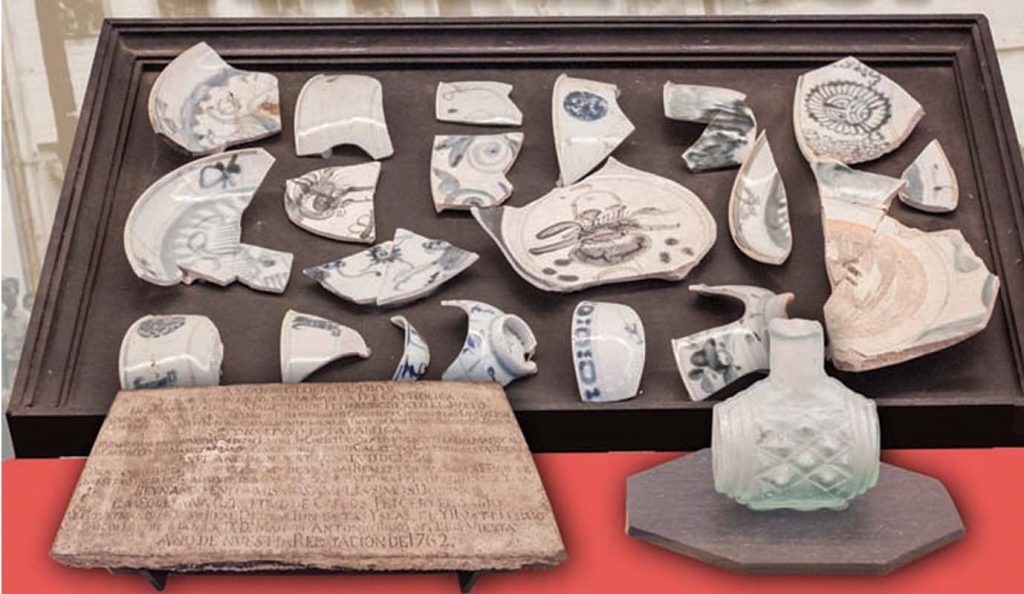

Infante knew that whenever construction or repair work was done on the school ground, porcelain shards, old bricks and bottles were unearthed. In 2011, he began collecting and preserving these reminders of Binondo’s past. With what he has gathered, he put up a museum inside the school.

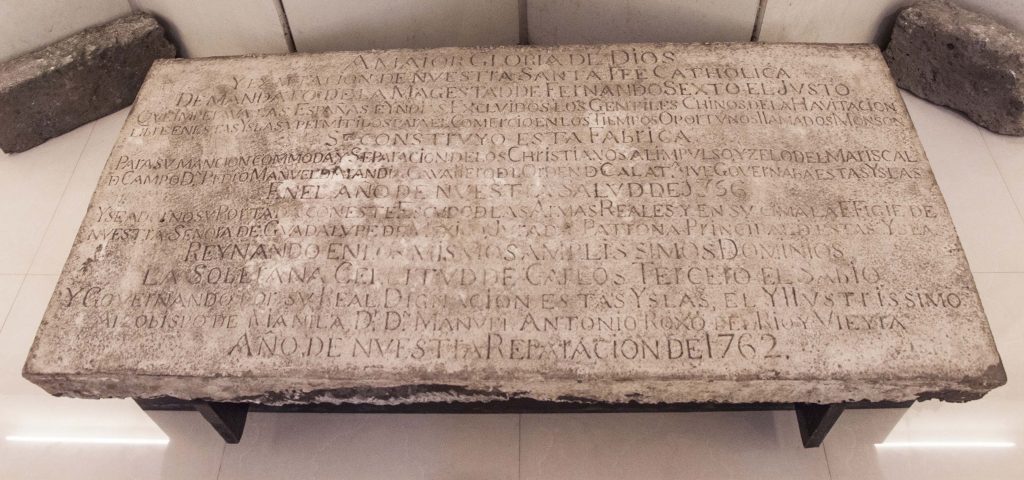

Infante is not the school’s history teacher, nor does he have a degree in archaeology. He is a graduate of Industrial Education from the Technological University of the Philippines. After graduating in 1991, he started teaching livelihood education to grade school kids. He noticed that the school had a big granite marker measuring 5 ½ by 2 ½ feet along the interior perimeter wall in one of the school buildings. What made it stand out was a dedication carved on the stone marker. The teaching staff assumed that the dedication was in Spanish, but none of them were able to read it.

In 2011, a new principal, Dr. Violeta de los Santos, was assigned to the school. What set her apart from other principals was her strong love for history. At her previous posting at the Francisco Balagtas Elementary School in Sta. Cruz, Manila, she set up a small museum which, unfortunately, burned down in 2007. So when she came across the stone marker at Pedro Guevara Elementary School, she asked some of the teachers to research about the marker.

Since they could not understand the language, De los Santos advised them instead to look up the names on the marker. Infante searched online, and slowly began piecing together the story of the marker and the Alcaiceria de San Fernando. He had daily meetings with De los Santos and shared the bits of information that he discovered. But as he was piecing together the story behind the marker, Infante realized that there was another aspect of the Alcaiceria’s legacy that was being neglected. These were the artifacts that turned up whenever there was a digging for construction or repair work inside the school.

Among the artifacts unearthed were porcelain shards, bottles and heavy granite slabs known as piedra china. The problem was that nothing was done to collect, catalogue and study them. More often than not, these would be carted away as soon as they were found. To prevent more artifacts from disappearing, Infante found ingenious ways to make sure that all the artifacts found on school grounds would be turned over to him. He told the construction workers to turn over any old bottles found. He warned them not to keep any of them as they might contain evil spirits that had been imprisoned inside the bottle during exorcism rites. He added how one teacher ended up with horribly swollen lips when he failed to heed Infante’s warning.

During lunch time, while the workers were on their break, he would go down the pit and try to retrieve whatever bits of artifacts he could find. More often than not, the items were caked in mud. Infante would gently scrub the grime away with a toothbrush. Once the dirt was removed, he would store the items in De los Santos’ office. Then, he would go online to try to find out what was it that was recovered.

While many of the artifacts that he dug up were Chinese porcelain ware, some of the more interesting items were from other parts of the world. Among them were the glazed ceramic bottles that once held ginger beer. Another was a rare ink bottle. The only other known example of this bottle was found in South Africa. But the most interesting item for him so far is a glass bottle from the 1820s. Based on his research, it was manufactured in Bristol, England in the factory of Henry Ricketts. Based on these findings, it would appear that the Alcaiceria sold all kinds of products from various parts of the world. An explanation for such commerce may be found in Lorelei de Viana’s book, Three Centuries of Binondo Architecture.

In 1783, another Alcaiceria was opened across the river in the Walled City, so the Chinese traders shifted their trade there, leaving Alcaiceria de San Fernando to focus on foreign traders aside from the Chinese as Spain opened Manila to world trade. In 2012, as the school was preparing an exhibit dedicated to the Virgin Mary, De los Santos decided that it was also a good time to hold a one-day exhibit of the Alcaiceria’s finds. A classroom was set aside as exhibit space.

Infante designed the display cases and explanatory panels. On hand to help was De los Santos’ husband Ricardo. A captain in the Delta Squadron of the Coastal River Guards, he and his men volunteered to help set up the exhibit.

What is remarkable is that one of Capt. de los Santos’ men understood Spanish, and helped translate the stone marker. His translation, verified by the National Museum, reads as follows:

With loving glory to God…Do we exalt the Holy Catholic Faith from the mandate of His Majesty, Fernando VI, the just statues of the Spanish Indies exclusive for the gentile Chinese inhabiting freely in these island and (as) permitted to (do) commerce for the opportune timed known as monsoon. Thus constitute the establishment for the public mansion providing separation from the Christians with the same orientation with the zeal of the camp marshal, Don Pedro Manuel D’Arandia, Knight of the Order of Calai, for the governance of these islands…In the year of our salvation, 1756. And the adornment of the portal of the city more the regal and with the miraculous effect of our Lady of Guadalupe of Mexico. The most worthy and principal patroness of the island. In the reign of the most ample dominion under the sovereign term of Carlos III who heads and governs with royal dignity the island and with the most illustrious archbishop of Manila, Don Manuel Antonio Roxo de Rio y Vierya in the year of reparation of 1762.

De los Santos opened the exhibit on Oct. 10, 2012, to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the Alcaiceria de San Fernando. Among the guests were heritage advocate Gemma Cruz Araneta and former Manila mayor Alfredo Lim. Both visitors were impressed with what De los Santos and Infante had done.

Lim presented them with a citation from the Manila City Hall. It was the first time anyone in the city’s school division received such an award. De los Santos was so elated with the award that she decided to make the exhibit permanent. Until today, it is the only public grade school in Manila with a history museum of its own.

Araneta, on the other hand, got in touch with the National Museum, which sent a team to check on the stone marker. After declaring it a cultural treasure, the museum made the school an offer. To prevent theft or vandalism, they requested that the stone marker be kept in storage at the National Museum to become part of an exhibit that will feature architectural features of historical buildings that are now long gone. The school will receive two fiberglass copies of the marker as compensation. The school agreed, and a team from the National Museum came to pick up the marker in June 2014. Eight months later, in February 2015, one of the fiberglass copies replaced the stone marker on the school’s wall, while the other copy is exhibited inside the museum.

Even after the exhibit, Infante continued searching and studying about the Alcaiceria de San Fenando from materials available on the Internet. One article that helped in understanding Alcaiceria’s history better was that by Go Bon Juan which appeared in the April 2011 issue of Tulay Fortnightly. Infante came across the article in 2013. Go’s regular column “Gems of History” featured a concise story about the Alcaiceria and how it started.

It was so informative that Infante used a portion of it on the exhibit panels of the museum (with proper credits to Go).

Five years after the exhibit, De los Santos has retired but Infante still teaches at the school and manages the museum on his own. He claims there is still a lot of work to be done. In fact, he believes that the school grounds still has more artifacts waiting to be uncovered – he is just waiting for more opportunities to dig around the school.

In the meantime, he has found other ways to improve the museum. In January this year, he started a project to build a scale model of the Alcaiceria based on his interpretation of the original plans. Using cardboard and glue, he was able to finish the project in just eight days. Because of his efforts, Infante has been receiving a steady stream of visitors, mainly students, teachers and professors. The former director of the Art Museum at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Peter Lam, is quite impressed with what he has been able to achieve. “The installation and explanatory panels on the display of pottery shards and glass bottles are very well done. Good information of the background of the site and the context of the excavated broken pieces.”

Infante is firm that the museum be open to the public and that anyone can come in and view the artifacts on display. All they need to do is to call up the school ahead of time and he will be ready to share with them the story of the Alcaiceria.

For museum visits, please call the school at 521-1508 to make an appointment. Museum hours are Monday to Friday, 1:30 p.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday is by appointment only. Entrance is free, but donations are welcome.