I’ve always thought of myself as creative. My constantly restless hands have this urge to do some kind of aesthetically productive work. That search for an artistic endeavor led to my discovering Chinese painting.

Most Chinese painting exhibited in museums and Chinese homes are typically scrolls of landscape in black and white, or with minimal bright colors. Rugged mountains, a pair of goldfish or koi, birds, bamboo, tree branches with flowers – these are common themes in Chinese painting, mirroring the Chinese deference to nature.

The ink washes echo a certain spontaneous yet flowing rhythm. The paper (宣紙) holds life in a composition that bears no horror vacui and the whiteness of pressed barks and reeds becomes part of the art.

First encounter

My first try on Chinese painting was in Taipei, Taiwan. My Belgian-Thai classmate asked me to take classes with her and we started taking weekly afternoon classes in a small studio house along Heping East Road. Our teacher was past 80 and his health was obviously deteriorating, but when his hand took a brush, it’s as though life is resurrected and flowed through the deftness of his wrist and fingers.

I marveled at how time seemed to stand still in those minutes as his skill transformed a plain white paper into a painting of tree branches and plum blossoms. I tried to do it, after weeks of getting bored with the basic strokes he had repeatedly asked me to do. I thought of Chinese painting as a Lego: I thought I’ve mastered what’s needed to put together a masterpiece.

Yet, when I placed the tip of my horsetail brush on paper, black ink scattered heavily and quickly. Then my teacher said, “熟能生巧” and wrote those four Chinese characters on my bleeding paper. Literally, it means “ripeness (maturity) gives birth to skill.” The English translation is “practice makes perfect.” Yet, I don’t think it’s how much practice that makes your art perfect, because some practice only for a short while yet manage to come out with a masterpiece while for some, it may take a whole lifetime. I suppose it is when you reach that point of familiarity or that state of maturity in the craft that the artistry comes out.

Overly-ambitious

In reflection, it wasn’t lines, circles and concentric lines that were my first lessons in Chinese painting. It was those four characters that became part of my everyday life. Being creative, I’m spontaneous and often unstructured, confident that as long as I’m passionate in doing something, I’ll be good at it. Chinese painting has taught me otherwise.

In fact, mastery of strokes gives us freedom to produce great work, whereas superficial knowledge merely binds us to a wash-out output. When I tried to do my first painting, this Chinese idiom epitomized my attempt: 畫虎類狗 or drawing a tiger but ending up with a likeness of a dog, which means ending in failure because of over ambitiousness. I knew I was still a long way to 生巧 or in being skillful at this art, and taking lessons from a master teacher is the right path for 熟 or maturity.

Beauty out of ashes

As I continued in my Chinese painting, I realized how I can’t make a mistake, or if I did, I can’t erase it unlike writing with a pen. No one has yet invented a Chinese ink eraser and the more I try to cover up, the more messed up my paper would become. This reminds me of another Chinese idiom, 將錯就錯, meaning that once a mistake has been committed, it’s a mistake and we just better do something about it.

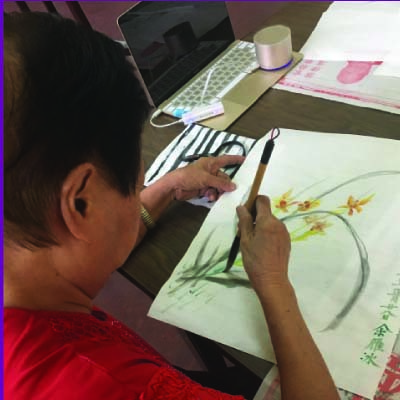

Recently, my sister and I have been taking Chinese painting lessons with artist Cesar Cheng. We went to see the grandmothers at the Home for Aged Filipino-Chinese women. We thought it would be good to have a Chinese painting session with them and indeed it was!

One grandmother had accidentally sprinkled black ink on what was supposed to be empty space after she had put strokes of branches on her paper. Quickly, she drew butterflies and birds and said she couldn’t do anything to delete it so she remarked how flowers would surely have birds and butterflies flitting around them. It was a beautiful response to a seeming tragedy. 將錯就錯 in action!

This is another important lesson I learned in this Chinese painting journey: You cannot undo what has been done, but you can correct it to make it beautiful. In Chinese idiom, it’s 轉禍為福 or transforming a misfortune into a blessing, and surely, the butterflies and birds are more a blessing than a curse for the flowers. We cannot control everything that happens in life, but we can adapt our reaction to it. This is another treasured lesson in Chinese painting.

Chinese painting is a dance between the artist and water, brush, ink and paper. Like a dance, it’s both an expression and impression of all the senses of an artist. And while getting to the finale, Chinese painting continuously imparts life lessons throughout the journey.