Tourism is a trillion-dollar – and still growing – global industry. United Nations World Tourism Organization records show that in 2015 alone, there was a 4.4 percent increase in international tourist arrivals, reaching 1.18 billion travelers. Because of this global boom in travel, tourism has emerged as the fifth most important industry in the Philippines. In 2015 earnings from the tourism industry contributed about $5 billion or 10.6 percent to the country’s gross domestic product; with an estimated 4.7 million Filipinos directly employed in the tourism sector.

But how did tourism take root in the Philippines?

Archaeological evidence indicates that people have been traveling around these islands way before the Spaniards. Such travels involved trade, diplomacy or war. The Sultan of Sulu who traveled to Beijing to pay tribute to the emperor is a case in point. What is more uncertain is whether any such travels were done for leisure.

During the Spanish colonial era, most travel involved trading between coastal towns and cities. The rivers and seas help linked the settlements. Mountains and forests formed natural barriers in the interior spaces of most of the islands. As road-building technology was not well developed, communities located on mountains or near forests were considered remote. Some of the more common reasons for traveling during the Spanish colonial period included getting an education, searching for work and going on a religious pilgrimage.

A popular journey was visiting the Church of Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage in Antipolo. In May, pilgrims seeking the Virgin’s blessings and protection would board boats near Quiapo, heading upriver to either Cainta or Taytay. Since the church was located on top of a hill, visitors took transport either in hammocks carried by crews of men or by horse-drawn carriage. After the pilgrimage, some visitors would go bathe in a nearby waterfall known as Hinulugang Taktak.

During those times, traveling to foreign lands was very slow and very expensive. Traveling to Spain, for example, took as long as a year via the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade route. Thus, a popular option was to stay at rest houses, which were frequently located on the edges of towns or city, so travel time became shorter. Some rest houses were run by religious orders such as the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe in what is now Makati. But this was exclusive only to religious workers and high-ranking colonial officials.

There were also privately owned rest houses. A good example would be Malacañan Palace, which was originally owned by businessman Don Luis Rocha. During the latter half of the 19th century, the Spanish colonial authorities introduced innovations such as railroad, electricity and telegram. As Manila opened to world trade, non-Spanish businessmen, diplomats and sailors began visiting the city.

As their numbers grew, it became apparent that the standards of Manila’s inns were no longer adequate. The city needed a first class hotel.

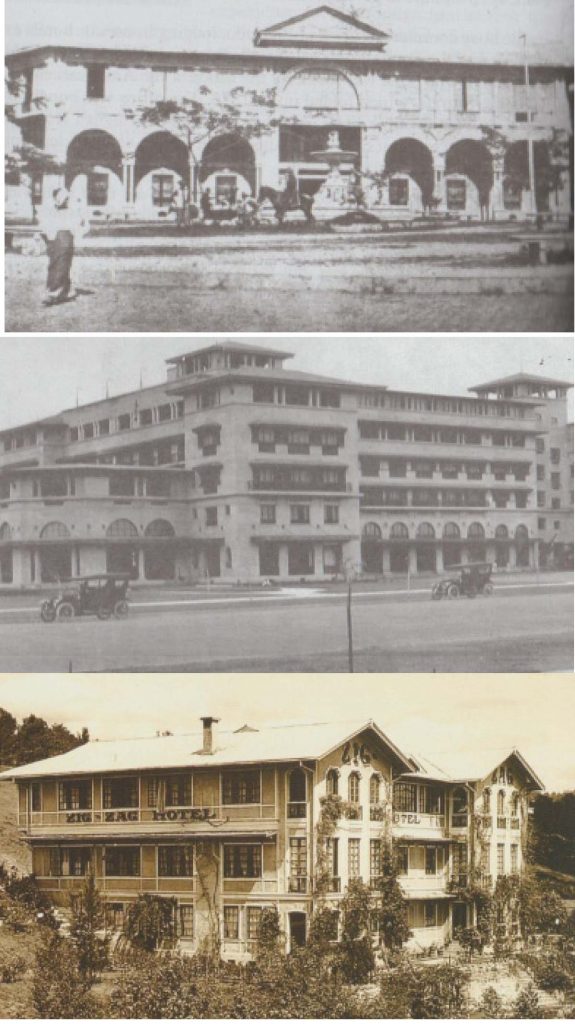

So in 1889, the city’s first deluxe hotel, Hotel de Oriente, opened. When the United States replaced Spain as the country’s new colonial administrator in 1898, one of their goals was to make Manila look more like an American city. Hotel de Oriente was deemed inadequate and considered a symbol of the Spanish-era Manila, and was replaced with a bigger and more modern hotel.

On the commemoration of American Independence on July 4, 1912, the Americans opened the Manila Hotel, which quickly became and is still one of the city’s most important landmarks. America began exploiting the mineral and forest wealth in the country’s mountain regions, and soon realized how much cooler the area was compare to the coastal areas. They converted a remote rural settlement called Baguio into a city. Because of its cooler temperature, it became a popular destination during the hot summer months.

During the first half of the 20th century, the number of foreign travelers were still small and limited to the capital city of Manila. It was the country’s main point of entry, as this was where the main harbor was located. The country then had one of the of world’s longest passenger piers, Pier 7. The first scheduled trans-Pacific passenger flight from San Francisco was done in 1935. Since Manila did not have an airport then, Pan American Airline would use huge flying boats known as the Pan Am Clippers that would land on Manila Bay. Where before the journey by ocean liner took two weeks, Pan Am was able to reduce travel time down to 59 hours with four stops. But it was far from the age of mass tourism as each plane could only accommodate 25 passengers.

Anticipating the growth of civil aviation in the country, New Zealand-born businessman Laurie Nielsen opened the country’s first civilian airport in 1937. It was from this airport that the country’s first airline, Philippine Airlines, first flew in 1941. Because the country’s road systems then were not extensive, local travel was very limited and difficult. Only a few places outside of Manila, such as Baguio and Taal Volcano, were developed specifically for tourism. Public transport such as ships, buses and trains were unreliable and unsafe.

After World War II, the government maintained its pre-war view of tourism. But one Filipino, Modesto Farolan, saw tourism’s potential. He was serving as the country’s first consul general in Hawaii, where he saw how tourism there was stimulated by the Hawaii Visitors Bureau.

Upon his return to Manila, he started the Philippine Tourists and Travel Association in 1950. Beginning with a small space at The Manila Hotel, the PTTA began its modest work of publishing and distributing brochures about travel in the Philippines. In 1956, the government began to acknowledge the potential of tourism. That same year, the Board of Travel and Tourist Industry was set up. Then in 1960, the government began keeping records of the number of visitors arriving in the country.

For that year, the country was able to attract 51,000 visitors. As numbers began to rise, a few foreign hotel chains took notice and decided to enter the local tourism market. The three earliest to enter were the Sheraton and the Hilton in 1968, and then the Intercontinental in 1969. By 1973, visitor numbers grew to 243,000. With the rising number of tourists, the board was reorganized as the Ministry of Tourism (now Department of Tourism). As awareness about tourism grew, Filipinos began seeing a career in tourism as a respectable choice. The University of Philippines responded to this by offering one of the first tourism degree courses in the country in 1977.

In anticipation of the growth in visitor numbers, more hotels and resorts began opening in Manila and a few key provincial cities in the 1970s. Among them were international brands such as Holiday Inn, Hyatt, The Peninsula and the Mandarin Oriental. Most of the newer hotels were geared toward the business and luxury markets. Because of the entry of these new luxury hotels, it prompted older hotels such as the Manila Hotel to undergo major renovations in order to keep up with the competition.

Instead of investing money in a marketing campaign, the DOT tried to promote tourism through hosting international events such as conferences and sporting meets. Among those that were held here were the Miss Universe beauty pageant in 1974 and the World Bank-International Monetary Fund meeting and the Ali-Frazer “Thrilla in Manila” boxing match in 1975. By 1980, the country was able to attract 1,008,000 foreign visitors. But the country was unable to sustain the numbers as it struggled with political instability in the 1980s. One of the major issues was the massive debt problem with foreign financial institutions. Unable to obtain loans, the country’s infrastructure began to fall behind. The foreign debt problem also led the local economy to collapse. With the local economy providing fewer jobs, some Filipinos tried to cope by going into prostitution.

Because of this, the country’s tourism image suffered further as it became known as a destination for tourists seeking cheap sex. Because the government was poor, the tourism department was unable to mount a marketing campaign to counter these negative images. Visitor arrivals dropped to 783,000 in 1986. Visitor numbers did not breach the one million mark again until two years later in 1988. Except in 1991 when it fell again, there were at least one million visitors who came to the country per year throughout the last decade of the 20th century.

By 1999, the country was able to attract 1.9 million visitors. This is because the DOT started investing in a marketing campaign. By then, many Asian governments were already conducting their own campaigns in an effort to create a brand image for their country, such as “Malaysia Truly Asia” and India’s “Incredible India” campaigns. The first campaign launched by the DOT was in 1994 with the slogan “Fiesta Island Philippines!”

The sector that gave tourism the biggest boost in the 1990s was local civil aviation. It was then that budget airlines were introduced and more provincial airports were opened to international flights. This move enabled local and foreign travelers to go to areas that were once too remote and expensive. The move helped stimulate tourism in provinces such as Batanes and Palawan. The island resort of Boracay became a popular international resort destination.

In 2001, the DOT relaunched the country’s tourism image with a new campaign called “Wow Philippines.” The campaign was deemed a success as the volume of visitors increased to three million by 2007. It was not easy for the DOT to achieve such a figure as it had to deal with a number of domestic and foreign events that affected tourism in general, such as the SARS epidemic and the hostage-taking crisis at a seaside resort by the Abu Sayaf group.

In 2000, the country saw the introduction of the long weekend, where the celebration of a public holiday was moved to the nearest weekend, creating a three-day holiday break. This gave Filipinos more time to travel around the country. In addition, an increase in income and car ownership, as well as a better highway network, enabled Filipinos to explore their own country like never before. Some analysts estimated that the number of domestic tourists could be as high as 50 million and contribute as much as P1.4 trillion annually in tourism revenues.

The DOT had a difficult year in 2010 as it faced three major crises. The first was the attempt to rebrand the country’s tourism image once again. The new marketing campaign was dubbed “Pilipinas Kay Ganda” (Philippines so beautiful). The use of the Filipino language in its slogan was heavily criticized, as it might not be understood in foreign markets. Others criticized the campaign’s new logo as resembling Poland’s tourism bureau logo. The embarrassment led to the new campaign’s pull out just weeks after it was launched and the tourism secretary was replaced.

The second crisis was when all Philippine carriers were banned from flying over European airspace due to safety concerns. With the ban’s initiation, Dutch carrier KLM became the only airline left that flew between the Philippines and Europe. The ban limited the number of European visitors to the Philippines until it was lifted in 2015. But the most damaging event to local tourism was the hostage-taking incident at the Quirino Grandstand, when a disgruntled police officer held a busload of tourists from Hong Kong hostage. The bungled rescue operation was broadcasted live around the world and the reputation of the Philippines suffered.

In 2012, a new marketing campaign was launched, dubbed “It’s more fun in the Philippines.” Within weeks of its launching, it was judged one of the top three smartest campaigns by global marketing campaign ranker, Warc 100. And though there were criticisms that it copied a 1951 Swiss tourism campaign, it did help tourist arrivals rise to 4.2 million.

To sustain the growth momentum, the DOT continued its campaign with a “Visit the Philippines Year” in 2015. Visitors figures reached 5.3 million. The following year, the DOT further increased visitor arrivals to 5.96 million, an 11.31 percent growth, with the “Visit Philippines Again 2016” campaign.

Indeed, Philippine tourism has come a long way, although challenges to local tourism are still numerous, particularly in the areas of security, marketing and infrastructure. But as more Filipinos become more aware of how tourism can affect their lives, the more they will see themselves as stakeholders. Hopefully more Filipinos will learn to come and work together in order to fully harness – and reap – the benefits of tourism.