“More Filipino than many Filipinos.” — Teodoro F. Agoncillo

“Through his unselfishness and heroism, General Paua had earned the gratitude of the Filipino nation to whose freedom and welfare he dedicated his life. He loved the Philippines as his own country …” — Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo

“The ferocity with which he contested every inch of soil lost to the American troops could also show his total transformation from Chinese to Filipino — in heart and in deed.” — Dr. Luis C. Dery

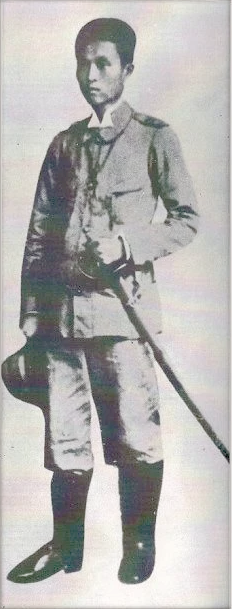

There are many little known unsung heroes in the history of the Philippine revolution. One of them is General Jose Ignacio Paua, the only pure-blooded Chinese general who supported the Katipuneros in the fight against the Spaniards and later joined General Emilio Aguinaldo’s army in the short-lived war against the American colonizers.

Paua was born on April 29, 1872 in an impoverished village of Lao-na in Fujian province, China. In 1890, he accompanied his uncle to seek his fortune in the Philippines. He served first as an apprentice blacksmith on Jaboneros Street, Binondo, a job he held for many years until he became an expert. His knowledge as blacksmith served him in good stead during the revolution. He became an expert in the repair of native cannons called lantakas and many other kinds of weaponry.

Paua was a young, handsome, and sociable fellow who easily made friends with Filipinos. His best friend was Pantaleon Garcia, a leader of the revolutionary army. Accompanied by Garcia, he attended meetings and fiestas in Cavite where he met Gen. Aguinaldo, Artemio Ricarte and other revolutionary leaders.

Aguinaldo admired Paua greatly because of his knowledge of the manufacture of firearms and for his deep sympathy toward the cause of the Filipinos.

At the outbreak of revolution in 1896, Paua quickly joined the army. Aware of the acute shortage of arms, he suggested to Aguinaldo to set up an ammunition factory in Imus, Cavite. With the help of his fellow Chinese blacksmiths, he finished the arsenal in two days time.

“Under his skillful supervision, old cannons and broken Mausers captured from the enemy were repaired; large bamboo cannons taped with wires were manufactured, numerous paltiks (crude firearms) were made, and thousands of cartridges were filled up with home-made gunpowder.” (Gregorio Zaide, p. 5).

Not only did he manage the factory, he also taught the Filipinos how to melt metals, including church bells, for the manufacture of the much-needed arms and bullets for the revolutionary army.

Aside from his own participation, Paua promised the support of his fellow Chinese in the Filipinos’ fight for freedom. In spite of his being a Chinese, he never hesitated risking his life for his adopted country.

Teodoro Gonzales, patriot-lawyer, described Paua in his unpublished memoir: “It was a strange sight in camp to see him — a dashing officer with a colonel’s uniform but having a pigtail. His soldiers were Tagalogs, all veteran fighters; yet they were devoted to him and were proud to serve under his battle standard, notwithstanding the fact that he was a Chinaman.” [Zaide, p. 9]

Paua’s valor was proven time and again in the battlefield, hence, Aguinaldo promoted him several times until he became a full general on September 26, 1898. He received his first baptism of fire in the Battle of Binakayan, November 10, 1896, which was personally directed by Governor General Ramon Blanco as an all-out offensive.

Paua reportedly “fought like a wild cat. He and valiant bolomen grappled with the attacking riflemen. Several times, he stopped the bayonet charges of the enemy at the left flank of Gen. Aguinaldo’s entrenched position.”

Despite their superior arms and number, “Governor Blanco sadly returned to Manila, with his tattered battle colors, shattered forces, and shiploads of wounded.” Candido Tirona and many brave patriots died gloriously in that fierce battle. Two days after the Battle of Binakayan, Paua was promoted from lieutenant of the infantry to captain.

Paua proved himself again and again in other attacks on Spanish garrisons, and confrontations in Zapote, Perez Dasmariñas, Salitran, Imus, among others.

On June 12, 1898, when Aguinaldo proclaimed Philippine independence in Kawit, Cavite and raised the colors for the first time, Paua cut off his queue (braid). When Garcia and the other comrades teased him about it, Paua said: “Now that you are free from your foreign master, I am also freed from my queue.” [The queue, for the Chinese, is a sign of humiliation and subjugation because it was imposed on them by the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty. The Chinese revolutionaries in China cut off their queues only in 1911 when the uprising which toppled the Manchu government succeeded.]

Later, tasked with raising funds for the empty coffers of the newly established Republic, Paua raised a staggering 386,000 pesos in Bicolandia alone, mostly from the Chinese. It was the largest cash sum ever collected by any fiscal agent of the Republic. Once, while making his collections in the early part of October 1899, he almost lost his life and his valuable cargo of 160,000 silver pesos. An American gunboat sighted them while sailing across Ragay Gulf towards the Tayabas coast.

Paua ordered the boat’s pilot to maneuver in the shallow waters near the banks, dumped his bags of silver pesos, and frustrated the pursuit of the steam gunboat. He went back and fished out his bags of coins the next day.

When the Filipino-American war broke out, Paua was again at the forefront of the battle. Taught in the rigid discipline of martial arts, he trained his men well. Among the very few battles won against the superior fire power of the Americans were those led by Paua.

Paua became a scourge of the American troops, who greatly feared his attacks. UP historian Prof. Luis Dery wrote: “The ferocity with which he contested every inch of Philippine soil lost to the American troops showed his total transformation from Chinese to Filipino — in heart and in deed.”

After the war, Paua retired in Albay and was once elected mayor of Manito, Albay. He told his wife and children: “I want to live long enough to see the independence of our beloved country and to behold the Filipino flag fly proudly and alone in our skies.” His dream was not realized because he died of cancer in Manila on May 24, 1926.

On Independence Day on June 12, 1989, General Paua was fittingly honored when Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, Inc., an organization of young Chinese Filipinos, in cooperation with the National Historical Institute, unveiled his bust at the Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit, Cavite and a nine-foot monument of this hero in Silang, Cavite.

Funds for the monument were raised from all sectors of the Chinese Filipino community as a tribute to this unknown and hitherto unsung hero of the Philippine revolution.

***

Short synopsis published in The Philippine Starweek 9, no. 16 (June 11, 1995): 8,12.