Whenever Chinatown in Manila is mentioned, what comes to the mind of people nowadays would be Ongpin Street in Binondo, which became the symbol of Chinatown in Manila since 1923. Formerly Sacristia Street, Ongpin Street was named in honor of Roman Ongpin.

Before that, was there a Chinatown in Manila? Where was it, if ever?

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, most of the Chinese stores were located on Sto. Cristo and Rosario (now Quintin Paredes) streets, but this area was not necessarily called Chinatown.

People who have some knowledge of the history of Chinese in the Philippines would know that there was an area called Parian in Manila where the Chinese and Chinese stores were concentrated, as well as restricted into, during the Spanish period. Only the Chinese who were baptized Catholic or married to a Filipina were allowed to live outside the Parian in areas such as Binondo or Tondo.

There were nine parians in different locations around Manila during the Spanish period. The first one was established in 1581 and the last one existed until 1860 when it was destroyed.

There were nine parians during the Spanish time because the stores and houses were made of light materials and easily destroyed by fire, or were destroyed during the Chinese uprisings and other times simply by order of the Spanish governor-general to demolish it. After the last parian was abolished, the Chinese were allowed to move to Binondo.

The best source on the history of the parian would be The Chinese in the Philipines, 1570-1770, vol. 1 by Alfonso Felix Jr. (1966), especially chapter IV of the book: “The Chinese Parian (El Parian De Los Sangleyes),” by Alberto Santamaria, OP. It provides comprehensive narration of the nine parians.

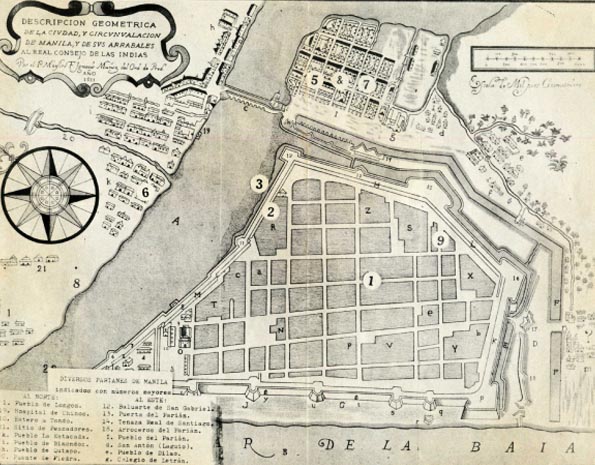

A 1671 map in the book shows the locations of the various parians in Manila. Arabic numbers marked the sequence of eight parians: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. The fourth parian was not included because it was situated outside the scope of the map.

This article does not discuss the history of the parian in detail. Rather, it introduces here a recent significant discovery of the famous scholar, Father Fang Hao (方豪) of Taiwan.

He researched on the history of cultural exchange between China and the West. In the course of his research, he visited El Archivo General de Indias of Sevilla in Spain in 1952. There he discovered 10 old maps of Manila, showing the locations of the Chinese parians. He made an annotation and narration of the Chinese history in Manila based on these 10 maps.

Fang’s article about the 10 maps he saw, titled, 流落於西葡的中國文献 (Chinese documents which found their way to Spain and Portugal), is found in the collection of his works published when he was 60 years old.

Below is the translation of the article where Fang described what he saw and learned from these 10 maps as “the most precious materials on the history of the Chinese in the Philippines.”

- Manila Map of 1671, drawn by Dominican friar Ignacio Muñoz, with Spanish illustrations, made on Nov. 28, 1671. With 14 churches, 12 of them Dominican churches, administrating 20 pueblos, with a Chinese village. The east portion of the map is the parian area, a “Three Kings” church was there. It also narrated the forces of Koxinga in China and Japan, and how he tried to retain Si Ming (思明, literally longing for Ming Dynasty) prefecture to fight against the Manchurians, and how he retreated to Taiwan. The distance between Taiwan and Manila is about eight days’ travel on medium-sized boat. In May 1662, Koxinga sent an envoy to Manila to ask for tribute and recognize him as king, otherwise, he would send an army to attack. There were those people who thought the Chinese in Parian were serious and silent threats and considered them “internal enemies.” They secretly installed gun powder at the entrance of the Parian, exploded and destroyed the whole Parian area and portion of the Chinese church and the Chinese hospital [San Gabriel Hospital]. We can see the row upon row of quite prosperous buildings in the Parian then. The wall, fort gate, field and hospital of Parian were marked with H-13, 18, 19.

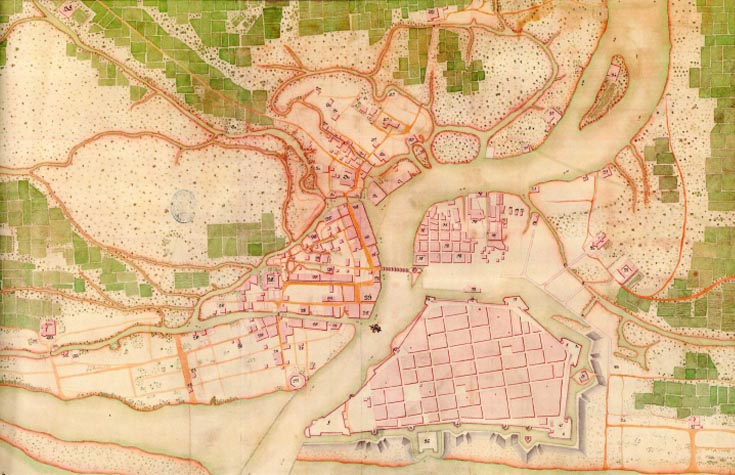

- Map of Manila 1762. On this map, in the location on the 1671 map where there were many Chinese residences, all the buildings were gone.

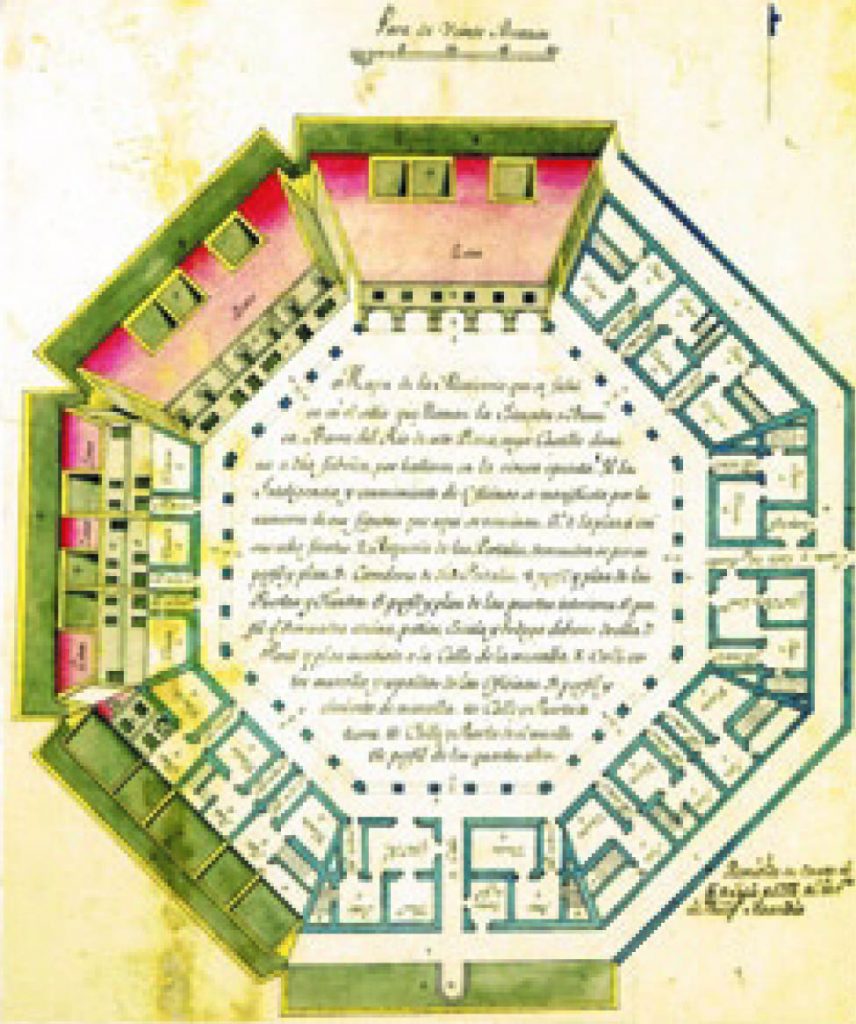

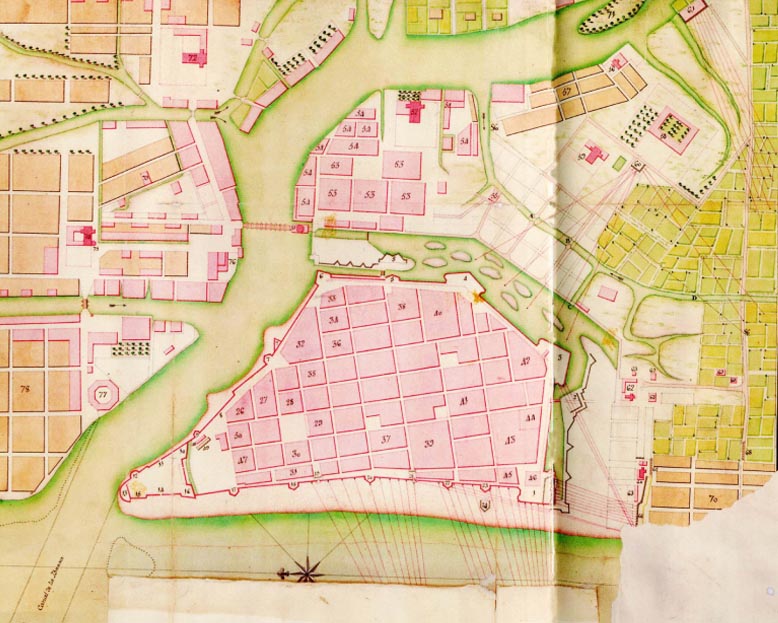

- Map of Manila 1763, drawn on Oct. 1, 1763, a year after the British attacked Manila. This map was marked with numbers and illustrations. No. 42 is a Chinese Dominican church. The church was in the shape of a cross. There were five big areas, all new buildings in the Chinese area. In No. 50 were eight areas, remnants of Parian streets. No. 72 is the Chinese hospital run by Dominican priests, the San Gabriel Hospital. No. 5 is the gate of Parian. No. 73, San Fernando Royal St., where the pagan Chinese hold annual great trade.

- Map of Manila 1764, drawn by Miguel Gomez on July 12, 1764. Just a year later than the previous one. Thus, almost the same, with newly built forts.

- Map of Manila 1767, drawn by Feliciano Marquez on Sept. 30, 1767 in Manila. Later than the previous one by three years. With few illustrations. A convent was added to the Chinese church. It can be seen that the number of Chinese buildings had increased in a span of three years. In the 1764 map, there were structures only in 20 districts. But in the 1767 map, there were already almost 60 districts. The change in the church is most prominent. The old church is in the direction of south-north, while the new one, east-west, also in cross shape. A big building at the north of the church is the convent mentioned in the illustration.

- Map of Manila 1770. Later than the previous one by three years. No. 19 marked with Parrochia y Convento del Parian. With few illustrations. At the eastern part of Parian, some 51 new small buildings can be seen.

- Map of Manila 1771, drawn by Dionisio Kelly on Dec. 15, 1771. It was only a year after the previous one but the Parian was destroyed almost completely. In many areas, broken lines were marked, such as No. 28, including 20 places. The illustration said “the Parian destroyed by a recent earthquake.”

- Map of Manila and Suburb 1779. With only the word “Parian.” At the southwest of Parian, across the river [Pasig], the place marked with letter C is San Fernando Royal St. where the Chinese came to trade for several days during trading season.

- Map of Manila 1783, drawn by Thomas Sanz on May 31, 1783. There were still broken lines indicating residences destroyed in Parian.

- Map of Manila 1785, drawn by Sanz on May 31, 1785. It can be seen from the map that after more than 10 years since the earthquake, houses in 13 places of Parian had been restored.

Fang was so fortunate to have the opportunity to discover and view the 10 old maps of Manila in El Archivo General de Indias of Sevilla, which all contained locations of Parian. He was able to annotate them and provide interesting and important information for us.

With Fang’s article as a guide, we are excited to discover the 1671 map illustrating the location of the various parians in Manila, which was found in Felix’s The Chinese in the Philippines. It is the first map mentioned and seen by Fang.

When we first saw the map in Felix’s book, we did not really pay much attention to it, except taking note of the location of the various parians. We failed to notice that it also indicated the location then (1671) of the fifth parian with letter I, Pueblo del Parian, and also No. 19, Hospital de Chinos, letter i, Pueblo de Binondoc and No. 13, Puerta del Parian.

Moreover, after further research, we found two other maps of Manila in the 18th century that also contained the Parian, from Mapping the Philippines: The Spanish Period published by Rural Empowerment Assistance and Development Foundation Inc. (2009).

One is dated 1766 and the other 1767. The 1767 one was mentioned by Fang while the 1766 was not.

What we want to show and emphasize is that although people might have the same knowledge regarding Parian, people, ourselves included, seldom have the chance to locate and look at Parian’s exact location and its formation in order to get a clear idea of how Parian was situated then.

In the 1767 map of Manila, the place right opposite Intramuros (then Manila) was the Parian, marked with No. 18, indicating Parrochia y Convento del Parian.

Other places of interest that are related to the Chinese are No. 12, Baluarte y Puerta de Parian, the canons there were said to aim at Parian just to watch over the Chinese; No. 27, Real Alcaiceria de S. Fernando; No. 28, Parrochia Convento y gran Pueblo de Binondo; No. 29, Hospital de Chinos.

In the 1766 map of Manila which focused more on Manila with more visible areas, the Parian opposite Manila was marked by Nos. 52, 53 and 54, with No. 53 indicating Pasesiones nuevas del Parian construidas de mamposteria perjudiciales a la Plaza and No. 54, Vesto del Parian Alcaiceria de los Chinos. No. 52 is Iglesia del Parian, Parroquia de Chinos a cango de los Dominicos.

Other places of interest that related to the Chinese are No. 76, Hospital de San Gabriel [Chinese Hospital]; No. 77, Alcaiceria eng. abitan y hacen su comercio los Chinos Gentiles and No. 74, Combento y Parroquia de Binondo adminis. de Pa Dominicos.

The Parian that appeared in the 1766 and 1767 maps of Manila would be the seventh parian. The location of the fifth and seventh parians is the Arroceros area now.

It is indeed quite interesting to learn more about the history of the Parian from these old maps of Manila. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 27, no. 7 (August 5-18, 2014): 8-11.