Say these in Hokkien: Di-si-di khong pue khong pue and di-si-di sam it di sam.

Our long time staff, Tulay artist Liza Lopez, still has these numbers memorized. So does one former staff, Gemma Ubay, who now lives in Cavite but still visits Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran in Intramuros, Manila.

I tried those Hokkien syllables out with my girls. Then switched to Mandarin. They recognized that I was dictating digits but had no idea what they really were.

These were the Kaisa phones when the office was still in Binondo. A Kaisa volunteer would make phone calls and dictate these over the phone.

Speaking of phones, can young children still use landlines? The first time Shobe saw a phone unit was at Kaisa. After she turned five and could be asked to do errands and simple tasks, I asked her to press 107 to give a message to our security guards. She pressed 107 and shouted, “Nanay, nothing happened!”

Achi went over to her, “You have to lift this kasi!” and promptly put the receiver to Shobe’s ear.

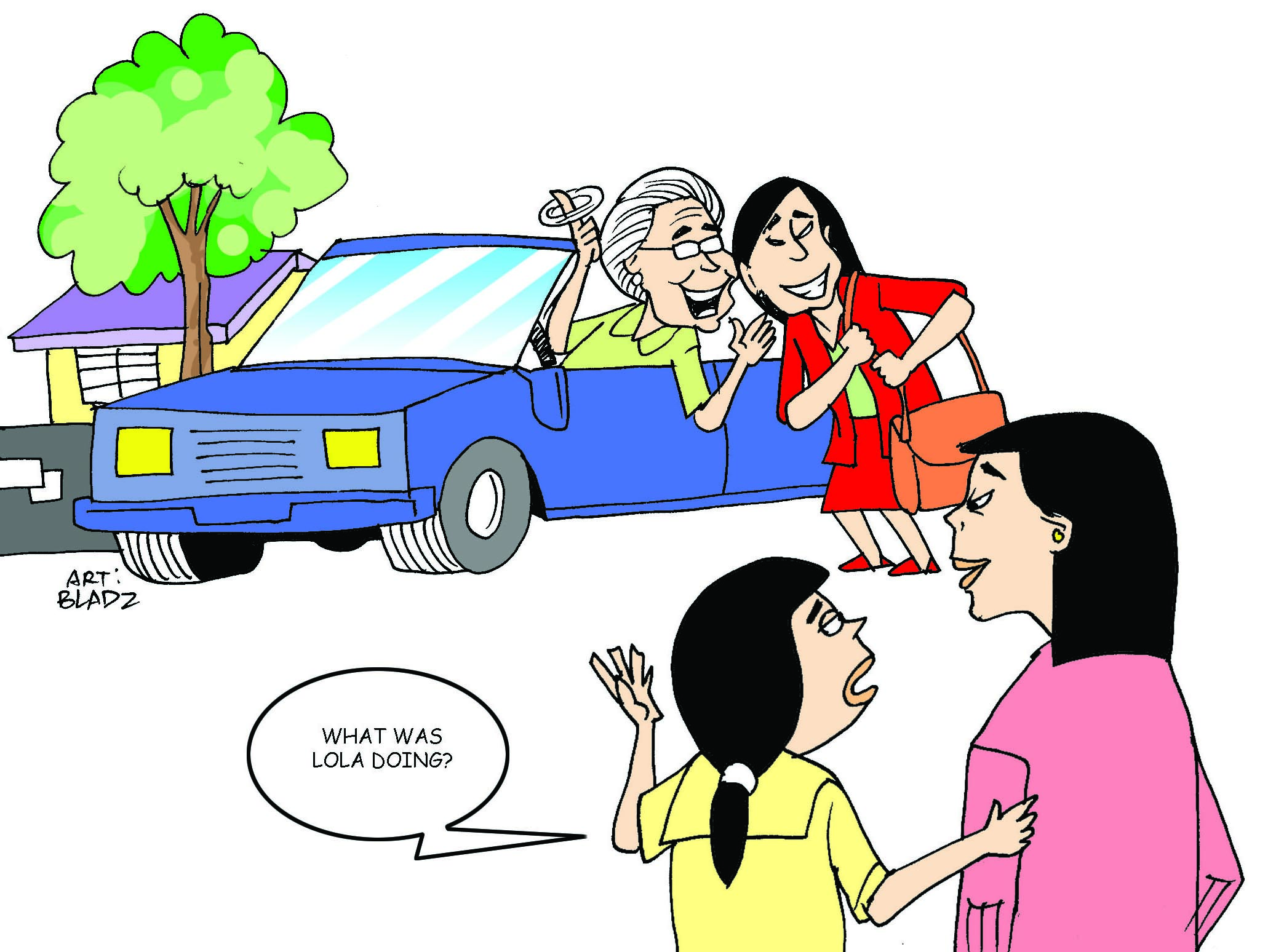

Dialing back the phone memories a bit further, a friend recounted this story a few years ago: her mom got into the car to go home. As my friend waved her off, she saw through the window that mom put one hand near her ear, and the other hand’s index finger making circular motions.

“Call me,” she is silently saying.

My friend’s niece, standing beside her, asked her aunt “What was Lola doing?”

And so it sinks in: this generation has not even seen a rotary phone.

This is also the generation that does not memorize phone numbers. Remember how we had to memorize the home number, papa’s office number, mama’s office number? Today, kids do not remember phone numbers because everything is programmed into their cell phones.

My girls have to memorize my mobile number. It is a security issue. They are too young to have their own cell phones. If they get lost in the mall, they know they should approach a security guard or enter a store and approach the counter and dictate my number to them, so they could reach me.

When Achi was in first grade, her class decided that they wanted to do “Telephone” as the topic for their investigatory project. Their final output was a small museum in one of the school’s cubicles that featured all they had learned. Thanks to Tulay editor Miriam Lieuson, the class got two old rotary phone units. The children were all in awe and quickly figured out how to dial the phone.

There is a downside to children and teens who are phone savvy. They are used to instant communication and expect to have instant feedback. Updating people about our lives are instantly done on social media.

When I was a child, my grandmother in the United States and I wrote letters to each other. I remember the giddy excitement of receiving mail in the post. I felt so important when I saw my name on the envelope. She would sometimes send my mail to the Kaisa office, and I felt doubly important because it felt like official correspondence.

I have tried to give this experience to the girls by giving them notes and cards, but it is just not the same as getting something in the mail.

What is different from writing letters and posting on social media? Aren’t the goals the same anyway?

Yes, but not quite. The act of handwriting itself fosters deeper thinking. We all know it is difficult to write by hand – fingers start aching, palms can start sweating, the letter becomes dirty when there are mistakes.

Therefore, before one writes down his thoughts, he has to think deeply about what he wants to write. We do not write everything that comes into our minds, just as we do when posts are easily deleted.

After all, why tire myself if what I write by hand is not useful after all?

Writing letters is a simple pleasure of an era gone by. I hope that when they are older, I can still teach the girls that not all communication has to be instant.

Another simple pleasure is taking a walk. I met Laurie when I first went to Catarman, Northern Samar in April last year. She is a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer assigned there. She asked me if it was a Filipino cultural thing or a province thing – none of her neighbors and new friends could understand that she was taking a walk but not going anywhere nor buying anything.

I could not answer her directly. Was taking a walk an American thing? In my entire life in the Philippines, I have never taken a walk. But when I lived in the U.S. 12 years ago, I often went out for walks.

The security problems in Metro Manila obviously preclude taking a walk. But Catarman does not have those safety issues. Was it then a cultural thing that we’re just not used to taking a walk?

We are used to walking a lot though. Those born and raised in Binondo and San Nicolas would attest to that.

From Binondo Church to the inner streets of San Nicolas is one kilometer at least, but we have often walked that far, even when I was six years old.

In high school, I walked from St. Stephen’s High School on Masangkay Street to the Kaisa office on Gandara Street, which, according to Google maps, is 1.5 kilometers away. If mom was not ready to go home when I arrived, I could wait for her, so I could ride in the car, or take the bus. I usually chose to take the bus, another half-kilometer walk.

I walked very slowly then and it took me 20 minutes to get from school to Kaisa. Even today, I base my walking capacity to those days in high school. Anything half an hour and under, for me, is considered walkable as this is less than two kilometers.

My kids, on the other hand, love taking the tricycle. When it is not hot and muggy out, I force them to walk.

Yes, evil nanay here, but they need the exercise. And I know they can walk the distance of 500 meters because they have walked farther than that. They never complain about walking when touring somewhere, so they need to suck it up and walk to lessons with their Chinese tutor.

I see many children and teenagers from Binondo schools these days taking the pedicab or tricycle. And then we hear about the tricycle driver who kidnapped them in exchange for ransom. (See Tsinoy Beats and Bytes, Sept. 17-Oct. 7, 2013 issue).

With our unsafe streets though, it is best to do everything with an adult companion. Require children to carry whistles that they should use when in danger. For adults, bring an umbrella that can double as a hitting stick when danger arises.

It seems that all of these “new” generation improvements are meant for everything to become as instant as they can. Remember waiting for leftovers to heat up in a pot while the tummy rumbled? Either that or we ate cold fried chicken or cold pansit. Today, nuke it in a microwave. Talk about instant gratification!

When I lived in the US, my roommates and I computed the cost of a microwave unit and electricity consumption versus cost of propane (gasul). Propane was cheaper. The experience definitely brought back fond memories of impatiently jumping up and down beside my grandmother while she warmed up champorado, then getting sent out for being too unruly in the kitchen.

My friend and I had a long email exchange about all of these obsolete childhood experiences and at some point, both of us realized that there are some things that children need to learn: reading an analog clock, reading a real map instead of listening to the voice on Waze, playing with toys rather than smartphones, and learning to look up words in a dictionary – hard copy, not online – in alphabetical order.

It is up to parents to decide which of their childhood experiences they want their children to have as well. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 1-2 (June 16-July 6, 2015): 11.