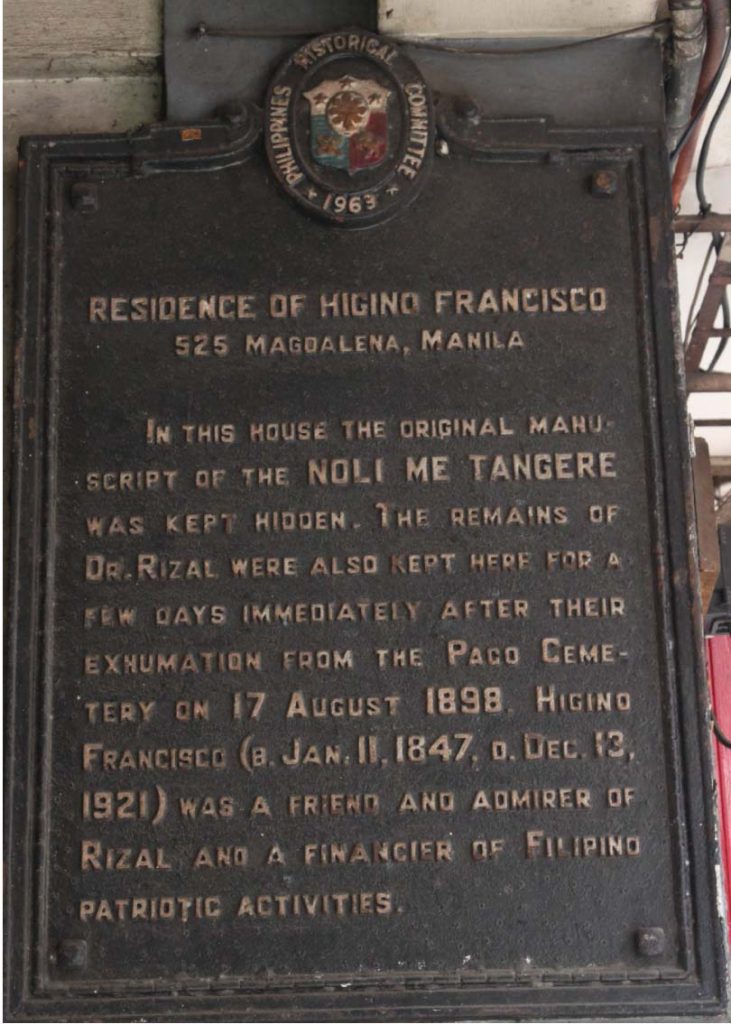

History can sometimes be found in the most curious of places, even in the back alleys of Binondo. Take for example this obscure historical marker in a driveway along Masangkay Street in Binondo. Since it is not visible from the street, only a few are aware of its existence.

The marker honors a Don Higino Francisco for two things: looking after the original manuscript of Noli Me Tangere by national hero Jose Rizal, and helping recover Rizal’s bones from Paco Cemetery. End of the story? It would have been, had it not been for two unrelated incidents that led me to a deeper appreciation of who this man was and what he did.

It started with an article by fellow Tulay writer Go Bon Juan. In one of his past columns, he wrote about a curious footnote in John Foreman’s book, The Philippines, which said Rizal’s brother and a sister owned a restaurant at 62 Calle Sacristia (now Ongpin) called the Dimasalang.

Without much effort, I found the restaurant’s location through a friend. I was showing Binondo around to a friend and members of his family. During lunch, his mother, Eduvigis A. Paderes, asked if she could be shown a particular historical plaque in Binondo dedicated to her grandfather. It turns out that Francisco was her grandfather.

This exciting revelation was followed by another even more surprising: Paderes claimed her family used to own the Dimasalang Restaurant, not the Rizal siblings!

But how could that be? Who really owned the Dimasalang? Now my interest is piqued. I decided to find out who truly owned it. But first I needed to know more about Francisco.

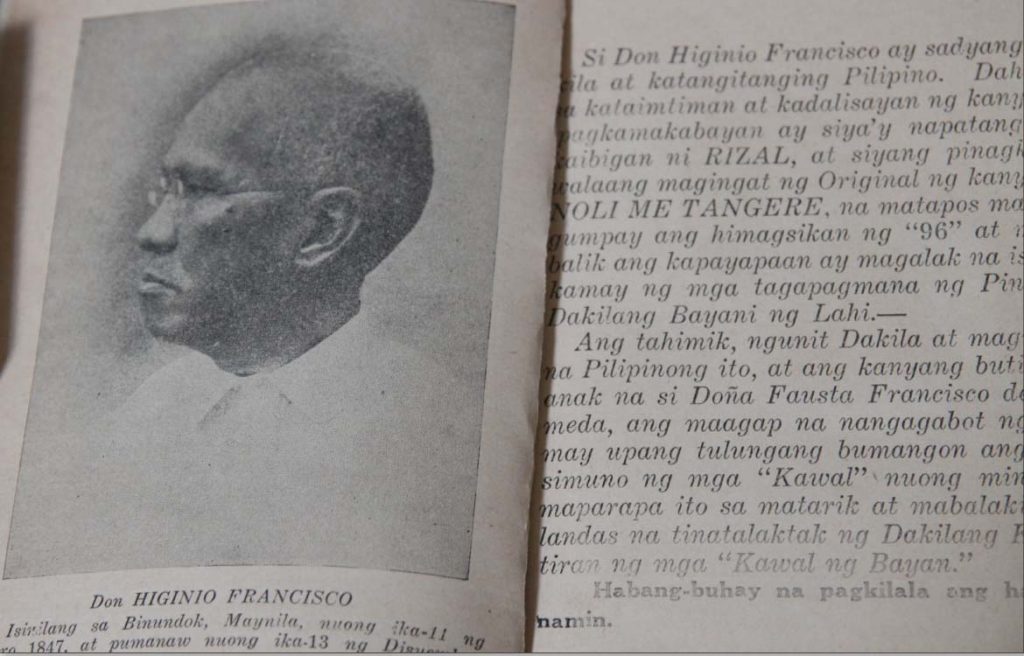

I was referred to the family archivist, Rene Resurreccion. Apparently, the patriarch was born in Binondo on January 11, 1847.

His parents were wealthy landowners from Biñan, Laguna, Jacinto Francisco and Lucia Prospero. Not much is known about his early life, except that he had no formal schooling.

But I presume his parents might have hired private tutors to give him a basic education, for it is said that he was adept in both Spanish and French.

Sometime between 1873 and 1874, he married Eduviges Almeda. A native of Laguna, she appeared to be from a wealthy family.

According to Resurreccion, her family made their fortune from the meat trading business. It also appeared that she was well-connected with the families from that province, among them Rizal’s family.

Resurreccion says it was probably through his wife that Francisco became friends with Jose Rizal.

In December of 1874, Francisco and his wife had their first child, Fausta. By then the couple had moved into a two-door accessoria (townhouse) at 525 Magdalena St. (Magsangkay Street today).

Their main source of income seemed to come from land ownership. This is backed up by family documents that showed Doña Eduviges inheriting several lots of farmland from her grandmother around Laguna.

The couple is also said to own a textile shop along Calle San Fernando.

Unlike Rizal who left us his thoughts in his journals and letters, Francisco left no records.

Nevertheless, his actions spoke loudly of his love for country. His children remember that the propagandist newspaper La Solidaridad was clandestinely distributed from his house. At great risk to himself and his family, he contributed cash to the Katipunan – a revolutionary society that worked to oust Spanish rule – and helped smuggle guns. He also assisted those who were facing problems with the Spanish authorities, such as sheltering members of Rizal’s family. He also helped lawyer Felipe Agoncillo (1859-1941) leave the country for Japan. From there Agoncillo went to Hong Kong and later joined the revolutionary government in exile led by Emilio Aguinaldo (1869-1964) in 1898.

Out of gratitude for his support, Rizal handed to Francisco the original manuscript of Noli Me Tangere before his exile to Dapitan in 1892.

In truth, Francisco never saw himself as a recipient of a gift, but rather as a caretaker. He went to great lengths to protect the manuscript. He first hid it in his house, but later moved it to his textile shop when he sensed that his house was about to be raided. When he heard that the store itself was in danger of being searched, he hid the manuscript at the foot of a nearby bridge.

While we may be familiar with the Katipunan’s attempted rescue of Rizal while he was jailed on board a ship in Manila Bay, not as well-known is Francisco’s plan to rescue Rizal while the latter was held in Fort Santiago awaiting execution in December 1896.

It was not clear how he planned to rescue Rizal, but it was clear that Rizal’s family dissuaded Francisco from carrying out his plans.

Learning of his plans to rescue Rizal, the Spanish authorities raided Francisco’s house. They had him arrested, claiming that he was hiding guns in his house. He was then sentenced to death by hanging. Fortunately, he escaped the gallows when the government granted general amnesty in 1897.

After the arrival of the Americans, Francisco was among those who helped Rizal’s family recover his body from Paco Cemetery. The hero’s bones were brought to Francisco’s house and were placed in a special urn made by sculptor Romualdo Teodoro de Jesus.

In a Philippines Free Press interview in 1953, Francisco’s son Jose said he remembered helping his father wash and clean the hero’s bones. He claimed that they did this on an embarcadero (a flight of steps where the boats docked) near their home along the Pasig River. It was sometime after this that Francisco returned Rizal’s remains to his mother along with the Noli manuscript.

Francisco’s desire to see an independent Philippines remained strong even with the arrival of the Americans. While he might hesitate to spend one peso for a new pair of pants, he did not think twice about contributing P500 to the defense of the newspaper El Renacimiento against a lawsuit filed by American colonial official Dean Worcester, who said the editorial Aves de Rapina (Birds of Prey) alluded to and libeled him.

Francisco quietly passed away in 1921. With all his patriotic deeds, he declined to be recognized a hero. The Philippine Senate and Congress invited him to attend a hearing in the 1940s to be declared as one, but he refused.

To honor his memory, however, the National Historical Institute in 1963 unveiled a marker at the site where his house once stood. It was during the unveiling that another facet of his life was made public: the patriarch had kept correspondence with another known Rizal admirer, Ferdinand Blumentritt.

The family then donated to the institute his letters with Blumentritt. There was also an attempt to honor Francisco by naming a street after him in Sampaloc. However, after a few years, the street reverted back to its original name Miguelin.

While writing this story, I was told more than once that among Francisco’s great deeds was opening the Dimasalang Restaurant. It was supposed to have provided a safe venue where the revolutionaries would meet and discuss issues. However, upon further investigation, it became apparent that it wasn’t he who opened the restaurant but his daughter Fausta.

Fausta’s name always came up in interviews with the family when the restaurant’s operation and management was discussed. Her father, on the other hand, was never mentioned. As well, magazine articles about him from the 1930s and 1950s never mentioned his opening any restaurant.

It is also unlikely that Francisco opened the restaurant, and the daughter Fausta managed it. One family anecdote says Fausta herself raised the start-up capital by selling a piece diamond jewelry gifted to her by a sister-in-law. Apparently, the in-law had lost a pair of pearl earrings lent to her for her wedding by Fausta. To make up for it, she gave Fausta that piece of diamond jewelry.

However, American author John Foreman, in his book, The Philippines, claims that Rizal’s family owned the restaurant.

During interviews with the Francisco family, the names of the Rizal family members were never mentioned with regard to the restaurant business. But Fausta did have other business dealings with Rizal family members.

It is possible she had an agreement with Trining and Rizal’s brother Paciano for the restaurant, using their family name as some sort of celebrity endorsement. Maybe this is why Foreman assumed that Rizal’s family owned the Dimasalang restaurant.

Another indication that the Francisco family owned the restaurant is that items used in the restaurant – such as the silverware and soup tureen – are with the descendants today.

The restaurant name itself has historical roots. Doña Fausta used the Tagalog translation of Noli Me Tangere: “Hindi Masalang.” Dimasalang is the contraction of those words. The term also served as Rizal’s pseudonym when he joined the Freemasons in 1883.

In a later interview at home, Paderes said the restaurant used to be at the corner of Ongpin and Yuchengco (formerly Nueva) streets, where Chuan Kee restaurant now stands. She was not sure when it opened.

However, the Watson’s Manila and Philippine Directory of 1902, according to Go Bon Juan’s article, shows that 62 Calle Sacristia was the address of a shop owned by a certain Coien Co.

Since John Foreman’s book was published in 1904, it is possible the restaurant opened between 1903 and 1904.

The elder Paderes claimed that when it first opened, the restaurant was considered high end.

She said Fausta ran the restaurant from the mostrador, a playpen-like enclosure where she worked as she looked after her younger children. Aside from in-house dining, the restaurant also offered bupete or what we refer to now as a catering service.

Dimasalang’s kitchen was presided over by Fausta’s sister Estafania and the cook Justino. Their specialties were dishes such as paella, pochero, cocido, galatina, chuletas (steak) and arroz ala cubana. They also served a specialty rarely offered today: Cabeza de Jabali, jellied pork wrapped in lettuce. Paderes says the family still prepares these dishes today.

Those who have visited the restaurant remember it as one of the first in Manila to feature a player piano. This was a piano operated by a perforated paper roll that made it play popular tunes of the day without the need for a person at the keyboard.

In a way, it was the jukebox machine of its time.

Family accounts say Fausta opened the restaurant because she had to feed a big family. By then, the family had sold many of its lands, Paderes said, to settle Francisco’s gambling debts. But rather than work for someone else, Fausta went into business.

However, she found it was not easy being an employer. She admitted to relatives that there were problems with her workers. Doña Fausta always worried that they were going to steal from her, after having caught them more than once trying to steal chicken relleno by hiding it under their hats. But still she gave her employees benefits as long as they did not rob her.

The restaurant lasted until 1926. Paderes claims Fausta closed the Dimasalang because of competition from nearby Chinese-run panciterias. But perhaps Fausta was tired of running the restaurant. She had told relatives she did not want to modernize or expand the restaurant.

Neither did she wanted to hire waitresses for fear of them fraternizing with the waiters, leading to immoral acts. She did not want to put up a bar in the restaurant for fear that her husband would start to drink.

Another problem was the issue of succession. She had been grooming son-in-law Leon Resurreccion to run the restaurant and her other businesses. But after his death due to a botched surgery, she decided that there was no one qualified to take over.

The lives of Francisco and his daughter prove that being in the background of history does not mean that their deeds are any less important than those in the limelight. Even though few know who they were, they still played vital roles in the unfolding of history.

To honor the memory of Francisco and his family, I now always point out the marker every time I do a Binondo walking tour. This way, I do my bit to spread awareness of this little snippet of history and the legacy of this man and his family. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 24, nos. 1-2 (June 14-July 4, 2011): 17-19.