Some parts of this article may sound mystical: this is not my intention. On All Souls Day, anything mystical-sounding should not be taken lightly.

In 2013, while filming a documentary on Tibetan medicine in India, our protagonist Dr. Dorjee had to leave abruptly – he was requested by a very high-ranking lama (Buddhist master) to help a team of Western doctors and scientists investigate the phenomenon called thukdam in connection with a recently deceased monk. As a Tibetan doctor familiar with Western methods of inquiry, he was invited to corroborate the findings.

Thukdam is a high form of meditative state entered into by deceased master practitioners whereby the body is clinically dead, but stays in an upright seating position, with the heart still warm and the skin remaining supple.

It usually lasts between three days to a month. The body should be left undisturbed while in this state, as the “consciousness” is believed to remain in it to complete higher meditative states to enlightenment.

When consciousness leaves, it is said that the body finally loses life. It degenerates to that of the ordinary corpse – frail, pale and cold.

After hearing the news, my filming team seemed to have lost interest in the Tibetan medicine story. We were bored with our current story and wanted the more exciting one. Not surprisingly, we were flatly denied and Dr. Dorjee left.

I have always had a strange affinity with death and dying. My first encounter was the demise of a close friend in Manila shortly after Christmas in 2006. I sobbed for two hours after receiving the call, not because of my friend’s passing but mainly because I realized that everyone around me will die sooner or later. At 18, I was inspired to uncover something bigger behind the issue of death.

In university, I went through numerous anthropological and psychological books on the subject, immersing myself in other people and their cultures that relate to death. However, I distanced myself from university acquaintances who talked about existentialist topics – to which death and dying is a perfect issue.

I also shied away from my professors who would probably have asked me to write a 20,000-word doctoral thesis on it.

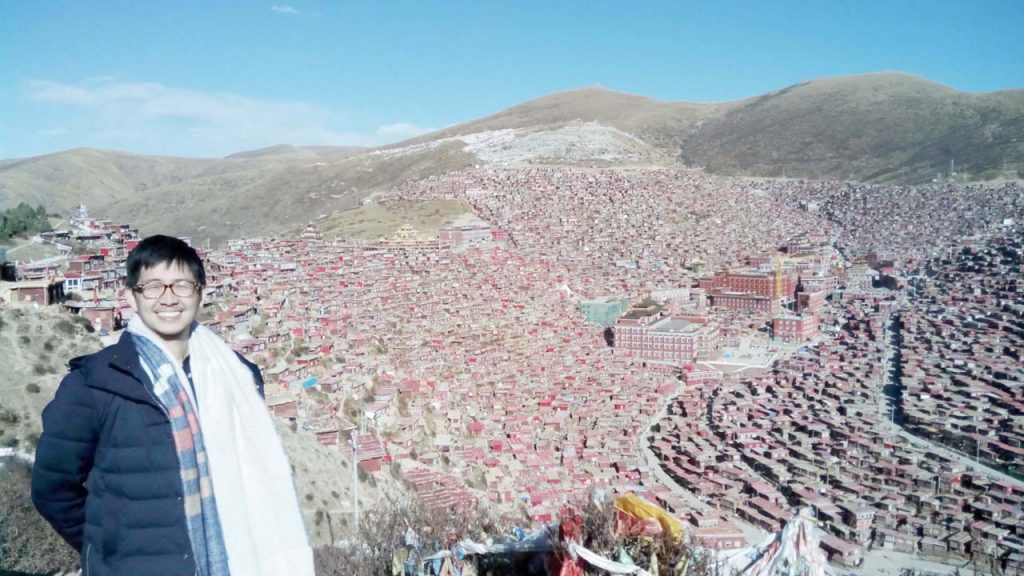

By 2015, I had traveled twice via 12-hour long bus rides in the inlands of Sichuan, China. In Larong Gar, a few miles from its village center, sky burial is still practiced until today. It is a custom whereby the corpse, with the consent of the living relatives, is chopped into pieces and fed to the vultures, metaphorically “burying the body into the sky.”

There were around 12 corpses up for offering during my stay there: the corpse of a monk, a few infants and the rest middle-aged men.

I was strolling around Larong Gar the day before when I heard about it and asked around, as I did not want to miss this chance.

My guide was a lady cook who exhibited disgust while telling me how to get there. “I have been cooking for 15 years here and I never thought of going there. Eww, thinking of it gives me goosebumps!”

The sky burial place was well constructed. I assumed the Chinese government took charge of the construction for tourist purposes. Resembling a small theater, it perfectly balanced the privacy needed by the relatives of the deceased whilst allowing onlookers to watch the event from a respectful distance. Monks and nuns served as ushers between the audience and the burial area.

I arrived an hour early for the event, and there were already a hundred people waiting. Arriving onlookers would pass through a series of sculptures of skeletons, the hells, heavens and the in-between states. In the center stood a 20-foot tall cement face of Yamantaka, or Lord of Death in Buddhist cosmology. People squat to enter his gaping mouth and touch the upper part with their saliva-moistened finger. It must be a blessing.

The sun was bright at midday. Were it not for the cold mountain winds, I was sure the theater would be less packed. Ten minutes before the bodies were brought in, the vultures started to land on a nearby grassland. They flew in not individually, but by throngs, until around 300 huge vultures waited, pecking at each other.

To put this in proper context, I need to discuss karma, rebirth and enlightenment briefly. In Buddhism, the goal is to purify our negative karma, to help generate positive karma and to exhaust all karma.

Karma is Sanskrit for action. Phala is the forgotten son of Karma, and it means effect. For any positive or negative intention and action done, a respective result will have to arise. Wishing “ma-karma ka sana” on someone who stole from us or slandered us? A Nepali monk would probably shake his head in disbelief and just smile.

Hence, rebirth. Rebirth sounds peculiar to many people and I am not in a position to debate. By extension, rebirth is a direct result of karma. If the actions today do not ripen today, it will have to ripen tomorrow.

The same mathematical principle applies to lifetimes. Enlightenment is when all karmas, positive and negative, are exhausted, when the sense of ego is cut to the root. It is a state of unending bliss. For the minority group of spiritual adepts, exhausting all karmas is the goal.

Therefore, sky burial has two purposes. It is a means to generate good karma for the soul of the deceased. By undergoing this “last act of selfless generosity,” much of the soul’s bad karma is purified.

It is considered a very noble act because we usually cling to our bodies very strongly, even after death. We want a mausoleum built, and if we had the means, beautiful and well-visited like the Taj Mahal or the Pyramids. So, to give away something so precious reverses a lot of self-centered negative karma and cuts a lot of ego.

The second purpose of the public burial is for the living to meditate on one’s own imminent death. This is one of the Buddhist practices that I feel the most affinity to. The meditation is not meant to create an artificial stoicism towards death. On the contrary, it is to soften us to the very core of our being.

Finally, one by one, the bodies were brought in. Each was wrapped in a sack, carried on the back or by two people on a stick hung across their shoulders. Some sacks were stained with blood.

After final prayers done in the Larong Gar temple, people entered. More than a hundred onlookers, young and old, chanted the mantra of Kuan Yin Ma with an eerie melody. “Om Mani Padma Huuuuuung Hriiiiiiiiii.”

Kids clung to the fence, trying to get a clearer view; I clung right along with them.

The burial masters drew the curtains between us and the arena, and they sliced and chopped the corpses. They first cut the scalp of hair and threw it aside. I saw the knots fly above the curtains.

That explained the yellow cylindrical pillar not far from us, with the top level containing some black material. These are the hair knots of all those who have gone before.

The stench started to permeate the place. Like in Disneyland’s “Jurrasic Park” 4D ride, the cold gusts of wind made sure everyone here had a 4D-experience as well.

Almost immediately, I heard someone a few feet away throwing up. Half an hour passed. Once in a while, I heard the sound of knife hacking thick flesh, and seeing the hand of the burial master scattering the flesh. Scattering made it easier for the birds, and made the meditation on death more real for the onlookers.

The vultures hopped nearer and nearer to the arena, until a few popped their heads into the curtains. Two male relatives shooed them away.

It was time. The burial masters dragged the curtains back and the throng of vultures quickly swarmed the arena, leaving only a few seconds for us to witness the bodies. The relatives quietly left the scene. It was the end of the “show.”

After another half an hour, I could see the skeletons in between fighting vultures. One burial master resumed his work by crushing the skeletons and mixing it with some concoction, then resumed feeding it to the vultures.

I left squinting from the punishing 2 p.m. sun, still processing what I had witnessed. I could not help but remember the monk in the thukdam state. They all ended up dead, but all reacted differently to it.

Unfortunately, most people I have met fail to get past the politics, the bickering and the rumors about the Tibetans (like how the Tibetans were once pawns of the CIA). Even more unfortunate, the remaining ones who do get past those get stuck at what Buddhism is already too popular for: mysticism, vegetarianism, spacing out and leaving worldly responsibilities to chill on top of hills.

Believe me, they are not cult fanatics who look forward to death. They are also far from the self-immolating monks we often hear about in the news. They have sacred vows and commitments not to commit suicide or to brag their inner realizations whilst still alive.

Cultures deal with death and after life differently. This sky burial ritual is a new experience I have yet to understand. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 10 (October 18-31, 2016): 16, 14-15.