Author’s note: This is a continuation of Relative Finder story, “Saga after the storm,” Tulay, July 5-18, 2016 issue.

How important can a piece of scribbled paper be? Sometimes, a nondescript note can mean a lot.

This is a case of one such letter that my friend Ed Lim made a photocopy of and had fortunately posted on Facebook a few months before Typhoon Yolanda ravaged Tacloban.

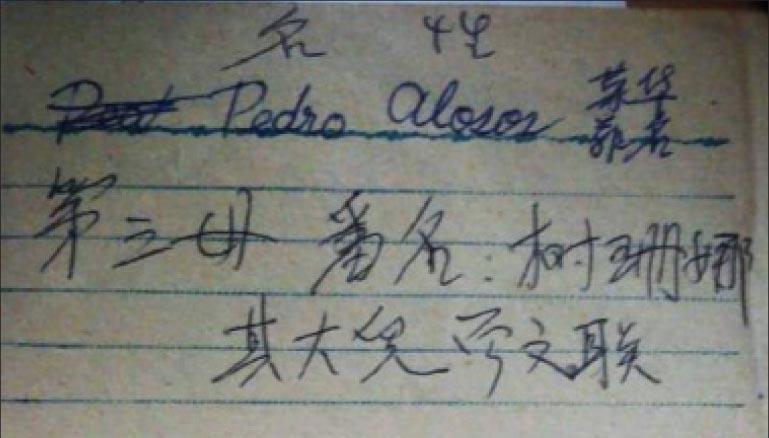

Written on it are several names, one in Filipino (Pedro Alosos), the rest in Chinese characters. This note is one of the items Chan Bon Kheng (曾文卿) sent Ed’s family to help his search for his lost family.

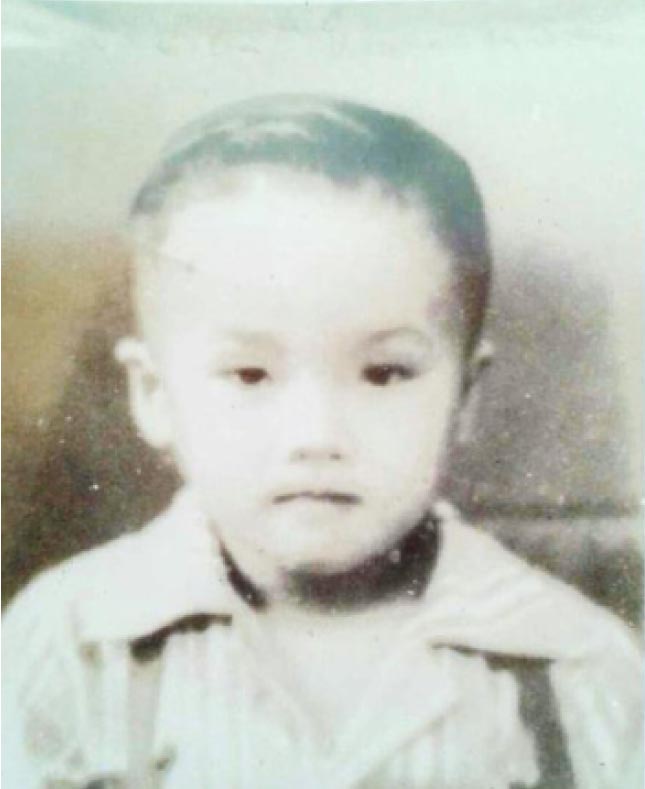

Chan Bon Kheng was born in the Philippines to a Chinese father and a Filipina mother before World War II. As a young boy, he was sent by his father to China’s Fujian province and did not return for over half a century. His entire immediate family, including his father, were left here.

In 2013, Ed and I were able to find some of Chan Bon Kheng’s lost relatives in Pagsanghan, a small town in the province of Samar. I frequently liaised with the family through Evita Chan-Dominguez, Chan Bon Kheng’s newly found niece. Her father Eugenio is from Chan Bon Kheng’s generation.

Not one, but two

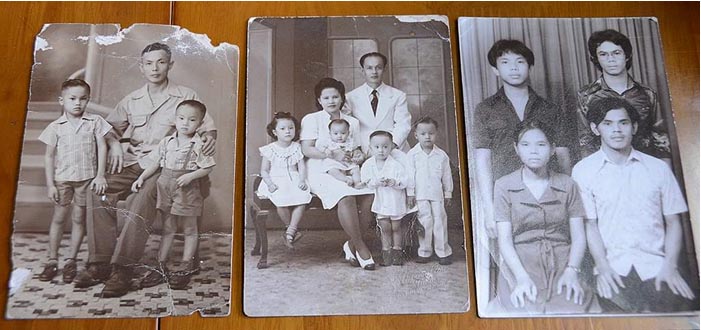

During our exchanges on Facebook messenger, Evita mentioned that there were actually two brothers of her father who were sent back to China: Eleuterio, the elder brother, and Pedro, the younger.

Both took the surname Alosos after the first wife of their grandfather who died when both siblings were still very young.

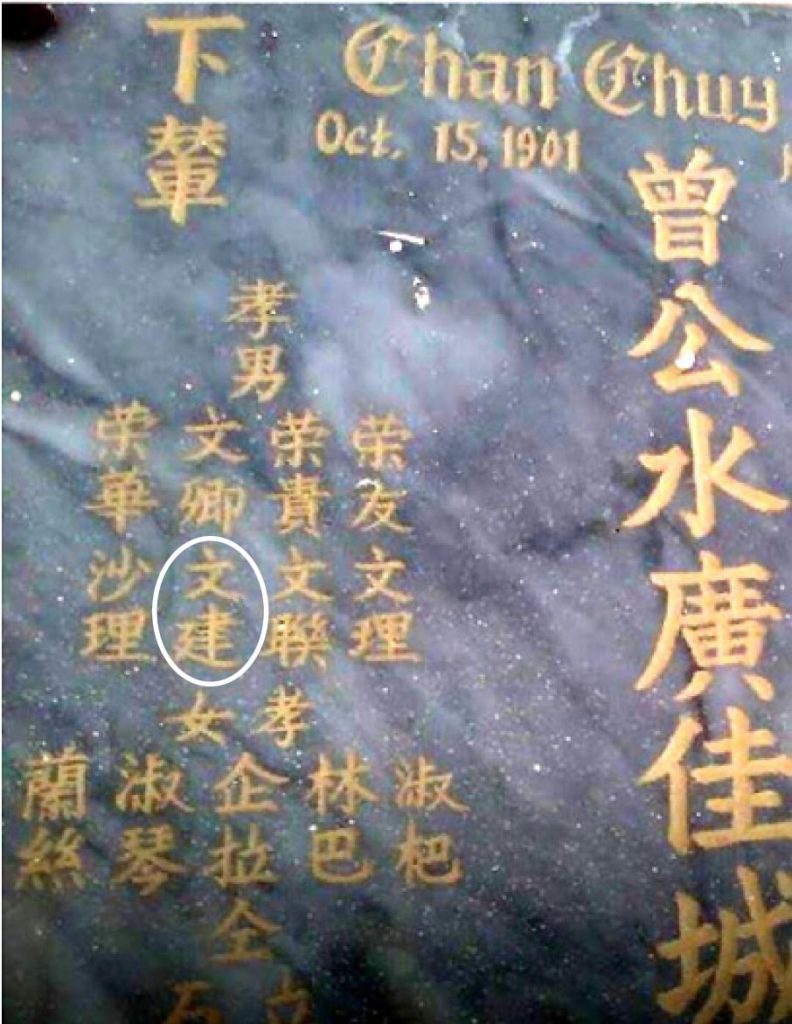

Evita’s uncle Romeo Reales (Chan Bon Dian 曾文聯), who took the surname “Reales” after the second Filipino wife of her grandfather, is the only member of their family in Samar who knows Chinese. He told the family that the Chinese name Chan Eng Hua (曾榮華) is the name of either Eleuterio or Pedro.

However, the name Chan Bon Kheng is not a familiar name to her family. I privately thought Chan Bon Kheng is one of Evita’s lost uncles, Pedro (Chan Eng Hua). For how else can Chan Bon Kheng have Evita’s father and aunts’ photographs?

Also, one of the notes that came with the photographs Chan Bon Kheng sent had the name Chan Eng Hua written on it, along with the Chinese name of Evita’s uncle Romeo. Both Chan Bon Kheng and Chan Bon Dian use the same generation name Bon 文.

Further, Eleuterio and Romeo’s father Chan Chuy Kong (曾水廣) had in his tomb a list that included Chan Bon Kheng as one of his male descendants. Chan Bon Dian’s name is also in the note as the main person to contact on behalf of the searcher named Pedro.

I surmised that Chan Bon Kheng may have, later in his life, have had a new nickname and/or a different Chinese name altogether, as practiced by other Chinese of his generation. Chan Bon Kheng must be Pedro, the younger of the two lost brothers.

Video chat in detail

So, it’s only Eleuterio who is yet to be found. Evita kept at me to confirm where the other brother was and what had happened to him.

On Evita’s birthday last Dec. 29, 2013, I was able to arrange a video chat with Chan Bon Kheng’s family in Fujian and Evita’s family in Pagsanghan. This could be a good opportunity to clarify the question on where Eleuterio is.

But deep inside, I dreaded what that eventuality could be.After successfully connecting those in China and Pagsanghan, I left the family to have this time to themselves.

Looking at both screens separately, I saw that Chan Bon Kheng had a strong resemblance to his long lost relative Eleuterio.

After the session, I asked Evita how it went. She replied her father and aunts were very thankful for the opportunity to finally meet their long lost kin. She added that she knew the experience was very emotional for them without their saying it.

All of them were teary-eyed. After more than 50 years, they cannot believe that they are seeing their long lost brother again.

One thing bothered them though. The relatives in China, including the elderly Chan Bon Kheng, insisted that there were no other siblings who were sent to China. Chan Bon Kheng did not have any brothers in China – all his siblings are in the Philippines.

Has Chan Bon Kheng become a bit senile and forgot about certain details of his childhood? Or perhaps he is hiding the true fate of Terio from the family in Pagsanghan?

Or even, perhaps without Chan Bon Kheng’s knowing, he has a brother in China? Or is it all just a matter of “lost in translation?”

We do not know. We were all confused.

I explained to Evita that perhaps, Eleuterio had been sent to China separately from Pedro. Or that he may have been adopted by another family. Or worse, perhaps Eleuterio went missing during the 1949 civil war.

I harbor these dreadful assumptions because I had experienced a similar situation in our family (“Relative Finder: Nine months,” Tulay, June19-July 9, 2012 issue).

My grandfather’s cousins Rufino Dy Chan (曾金沙/黄金沙) and Francisco Dy Chan (曾金弟) had been sent from Catarman, Northern Samar, back to China as young boys. At the onset of the Chinese civil war, both were kidnapped by the KMT and drafted as child soldiers. One of them was never heard from again.

After the video call, I did not receive any news from both families for a while. It looked like both sides were contented knowing that they now have a means of contacting each other. The good news of finding their long lost uncles spread.

On Feb. 22, 2014, I got a message from a Marites Reales. She said Evita referred her to me. She needed help in reconnecting with her relatives in China, especially her lost uncle. Because she is based in Manila, she would have faster Internet connection.

I originally thought this was a new family seeking help. But she turned out to be Evita’s cousin who is based in Manila. Marites is the daughter of Eugenio’s younger brother Romeo/Chan Bon Dian. Marites’ family used Reales as their legal family name.

She was very curious about this story of their family being reconnected after several decades. Based on the generation poem of the Longshan Chan, Evita and Marites are my aunts even though both are almost my age.

Through Facebook, Marites and I frequently chatted about our common heritage, the history of the Chan clan, the Chinese migration here in the Philippines and, most importantly, the long story of how we were finally able to reconnect their family. I kept urging her to go visit her relatives in China.

She was very interested, especially as she has traveled to Beijing. Finally on Dec. 9, she decided to make that historic visit on behalf of their family and started her visa application.

Travel adviser

With my extensive experience reuniting families in China and the Philippines, another hat I often take is that of being a travel adviser. Having traveled to China before, Marites didn’t have a problem with her visa.

But her American partner, Michael Milner, looked like he may have complications with his visa application. She was finally able to submit their visa documents on Jan. 7.

Marites kept me up to date with her travel arrangements, asking me for advice on all sorts of travel preparations – hotel, food, transport, even what to bring to her relatives as pasalubong.

I advised the best time to visit is during the Chinese New Year celebrations since China has only two main holiday seasons and Chinese New Year is the most important of the two, where most Chinese would return home to their families for a week-long holiday.

I had visited my relatives before outside of this period and it was embarrassing to see them go out of their way to schedule work leaves to entertain us. Hence, I strongly urged their visiting during the Chinese spring festival.

I recommended Quanzhou Overseas Chinese Hotel. Aside from its welcoming name to Chinese diaspora such as myself and Marites, the hotel with its English speaking staff is also conveniently situated at the heart of the historic quarter and is well suited to overseas Chinese. Its Philippine peso to yuan exchange service is also a plus.

I also told Marites that there are now direct flights from Manila to Xiamen, which is just an hour’s drive to our ancestral village at the outskirts of Quanzhou City.

On Jan. 11, she messaged me that she had booked very cheap promo tickets for herself and Mike. Flight date was during the 2015 Chinese New Year, as advised. Her destination was Guangzhou City.

Wait, Guangzhou City? That’s Guangzhou, capital city of neighboring Guangdong province, not Quanzhou City.

I asked her to rebook but she refused. The flights to Quanzhou are very expensive due to late booking and besides, Quanzhou is not covered by any promo. And as per the airlines’ policy, tickets cannot be rebooked!

So she planned instead to take the train from Guangzhou to Quanzhou. It was then that she realized how very far the two cities are from each other.

She conceded that this is going to be a difficult journey. She and Mike do not speak any Chinese. Aside from that, they are arriving in Guangzhou during the busiest time of the year, on the eve of Chinese New Year.

What to do? The saga continues. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, no. 8 (September 20-October 3, 2016): 16, 14-15.