In the Philippines, the 17th-18th century was marked by massacres and mass expulsions of the Chinese by Spanish colonial authorities.

In the 19th century, anti-Chinese agitations and discrimination continued to mark the Spanish rule in the form of imposed taxes higher than other foreigners and locals. Likewise, restrictive travel passes required all Chinese to obtain permits to travel. Those caught violating the travel permits were conscripted into forced labor unless they pay a high penalty.

The Chinese were also used as scapegoats. The Spaniards deliberately fanned native resentment by blaming them for the economic ills caused by Spanish misgovernment and neglect.

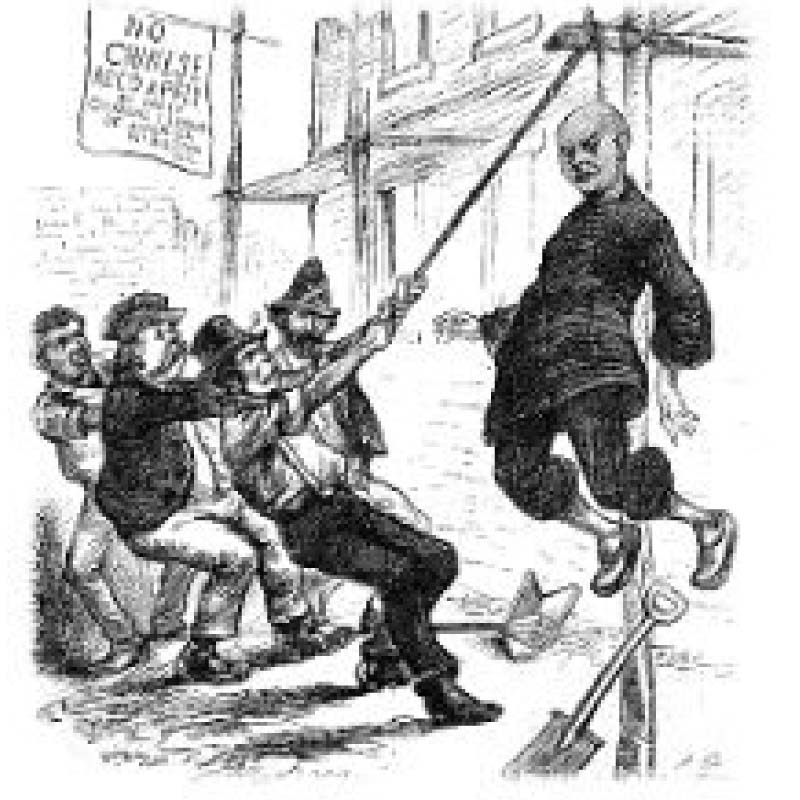

Under American rule (1898-1946), the Chinese also suffered from persecution and discrimination. Application of the Chinese Exclusion Act on the Philippines in 1902 was the most onerous form of legal discrimination against the Chinese. The Act banned laborers from entering the colony and allowed only professionals, merchants and sons of merchants to enter.

In 1919, the Chinese were blamed for a rice shortage which was really due to poor harvest. In 1924, again due to economic ills, anti-Chinese riots occurred in Manila, which spread to Cabanatuan and Nueva Ecija, north of Manila. The Commonwealth Government (1935-1946) was marked by the application of nationalization measures like the rice and corn trade in 1940 and the ownership of market stalls in 1941.

Philippine independence and freedom from colonial rule gave rise to a new form of Filipino nationalism during the Republican Period. Discrimination against the Chinese took the form of exclusion of the alien minority like the Filipino-First Policy in the 1950s and 1960s.

For instance, only Filipino citizens were allowed to take the board exams for licensed professions such as engineering, medicine, nursing, accounting, architecture, chemistry, pharmacy and law.

One of the most traumatic legislations that had a long-term impact on the Chinese community was the passage of Republic Act 1180 in 1954 which nationalized retail trade, the main occupation of Chinese businesses at that time.

In Korea, most literature on racial conflict mentions the “Manbo Mountain Incident (萬寶山事件)” which happened at the Manbo mountain region of Changchun, Jilin province in 1931.

The Japanese forced Koreans in China’s northeastern districts to relocate in order to build irrigation canals and develop surrounding farmland. Violence occurred between Korean and Chinese farmers.

Although there were no casualties, the Japanese spread false reports in Korean newspapers that numerous Korean farmers were massacred by Chinese mobs.

On the pretext of “protecting Japanese citizens” on Chinese soil, the Japanese deliberately encouraged anti-Chinese sentiment to drive a deeper wedge between the two groups and to create excuses for further intervention in northeastern China.

As a result of the rumor, angry Korean farmers retaliated against overseas Chinese merchants by pillaging and setting fire to their stores and houses. Many Chinese were beaten up and 142 were killed.

The incident damaged a lot of the properties of overseas Chinese in Korea and left a lasting imprint of distrust and suspicion between Koreans and huaqiao.

After Korean Independence in 1945, upheavals and unrest against the Chinese continued. During the Korean War (1950-1953), Communist China intervened on behalf of North Korea, and the Chinese in Korea became scapegoats for Chinese aggression against South Korea.

The huaqiao suffered crippling losses to property and livelihood during the war. After the war, they were subjected to progressively worse discrimination and neglect.

The most serious blow to the huaqiao in Korea was probably the measures taken by the Park Chung Hee administration.

These restrictive government policies, like the Warehouse Blockade Act, currency alteration and reform in 1952 and 1962, limitations in the foreign ownership of land, residential and property rights, restrictive Trade Law and unjust taxations, caused the decline of their livelihood.

The restrictive and discriminatory measures made it difficult for them to continue their businesses. In the 1990s, the rights of Korean Chinese were no better than those of other foreign migrant workers; they were denied residential rights and made subject to penalties if they overstay their visas in South Korea.

According to a court ruling, Korean Chinese should be accepted as citizens of South Korea only if they have North Korean citizenship, because the South Korean Constitution recognizes North Koreans as citizens. Moreover, the difficult and lengthy process of naturalization made it difficult for the Chinese to acquire Korean citizenship.

Restrictions and discriminatory policies prevented the Chinese Koreans from identifying with and integrating into mainstream Korean society or to assert a Korean identity.

Above all, they hindered greater economic success, professional advancement and greater positions of influence of the Chinese Koreans.

Likewise, because of these measures, many poverty-stricken huaqiao left Korea in search of a better life. Quite a number migrated to the US and came to consider these restrictive measures as blessings in disguise as they enjoyed better opportunities in America.

In comparison, the Philippine naturalization process was even more difficult, tedious and expensive before the 1975 Marcos mass naturalization process. Yet many Chinese opted to go through the process in order to protect business interests and further achieve economic success. This perseverance, as well as Marcos’ initiative, enabled children who were naturalized along with their parents to enter professions and engage in businesses previously forbidden to them. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 29, nos. 1-2 (June 21-July 4, 2016): 16-17.