Some time in late July, my friends and I discussed which classes we planned to take for the incoming school year. Our department was rather small, so there usually weren’t a lot of classes offered (there was only one class per course number). This upped our chances of being in the same class with our friends, so we usually tried to match our schedules with each other.

I had a break in between my Tap class and one of my Arts of the World class in my schedule. A friend suggested that I take the Renaissance class that fitted perfectly in the time slot of my break.

As another incentive, the professor who was teaching the said Renaissance class had also taught my Modern Art class which I enjoyed. My friend convinced me that it should be fun because of the professor and that I would be able to kill two birds with one stone, considering a quarter of a semester will be spent on Renaissance in my Arts of the World class anyway. So, might as well drown myself in Renaissance art in one semester instead of two.

Before attending the Renaissance class, I never dwelt much on the movement. It seemed like a pretty big deal in world history class, but the reason behind it never really got across to me. Maybe it’s because it wasn’t elaborated in high school. It was taught as a very important era for learning and the arts, but there was a lack of context to it. Truthfully, I thought Renaissance was kind of boring especially because of the types of subjects it was famous for. To me, it was just an era full of portraits, like the over-rated Mona Lisa, and religious paintings. These two types were quite common through most of the periods of art in between Classical and Modern, so what was it trying to prove? Why was it so special?

To further emphasize how dull Renaissance seemed, I kept thinking about how it would never be as mind-blowing and exciting as Modern art and its rule-breaking spirit. On the other hand, it still remains on top of the Classical art and Modern art on my list of choices of thematic electives. Classical Art had a heavier emphasis on form instead of color while Medieval just looked so cartoon-like. It certainly looked like the least evil among the three movements.

On the first day of class, our professor asked us about our expectations. I wasn’t too sure what to say. I guess I expected paintings, because what would a Western art class be without paintings?

So there, paintings…made during the Renaissance, because that was the title of thematic art class after all. In my mind, I listed down that we were going to learn of a revival of classical values as well, but I wasn’t too clear on what the values were so I decided not to write it down. I also expected a lot of memorization, mostly because the class was dominated by art studies majors (and having choices in an exam about paintings is just not how we live).

My concern regarding classical values was addressed during the whole of our next meeting. As per art history style, we tackled the context before the actual art movement because more often than not, movements were either influenced by or a reaction to the events that happened before them.

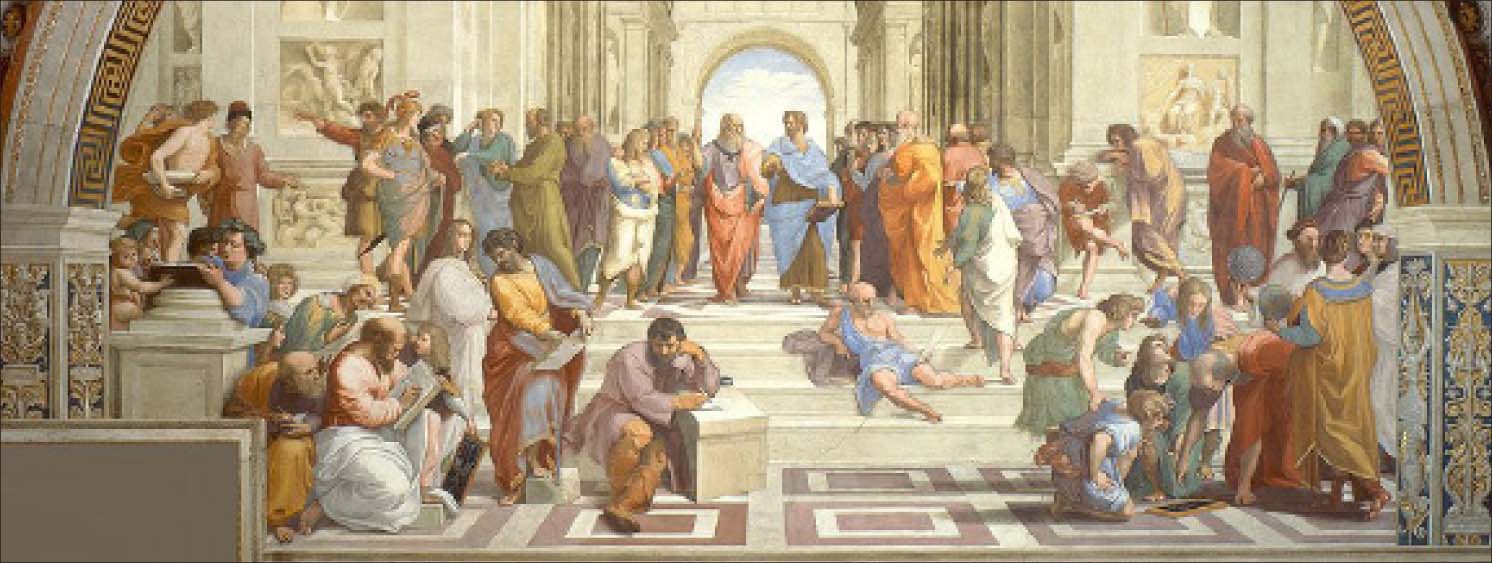

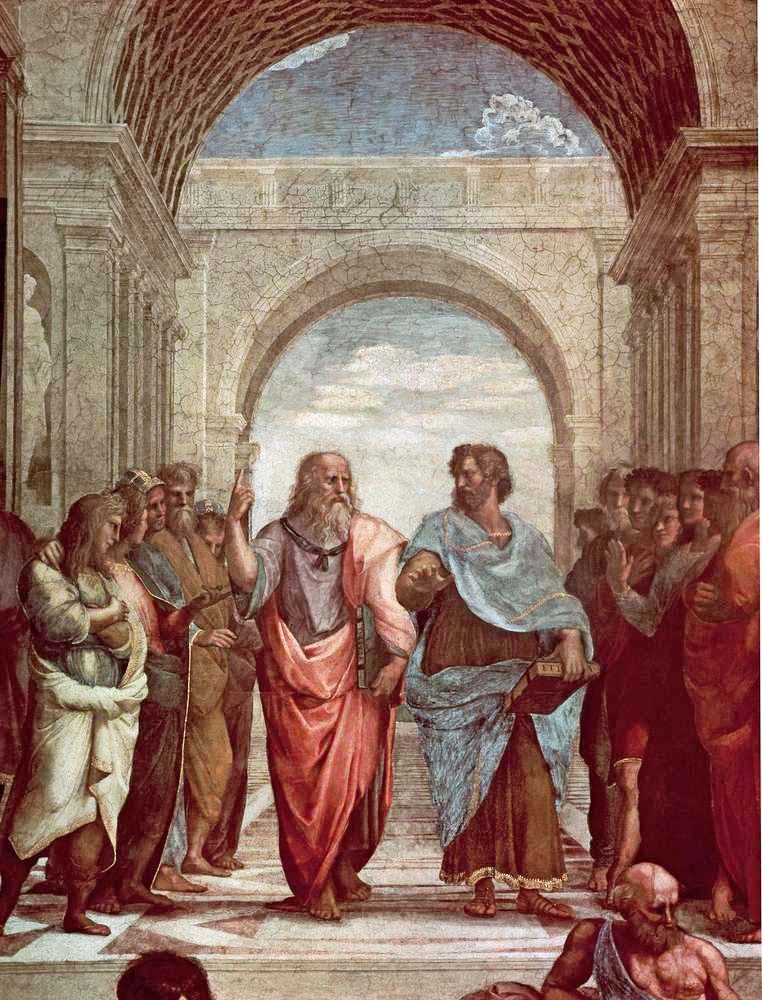

We discussed Plato, Aristotle and their philosophies on art, which would then shape the patron’s view of art during the Renaissance (here was the classical values that I was looking for) and its subsequent movements. The hold of classical values was just such a strong canon that it was the very reason Modern art was very controversial in the first place! We also tackled a bit of medieval art and why the mimetic feel was kind of lost during the time period.

On our third class, the main point of the whole Renaissance movement was set upon us: the importance of mimesis (ancient Greek meaning “to imitate”) and naturalism. This can be seen in Giotto di Bondone’s Madonna Enthroned. He was claimed to be the first Renaissance painter because he pioneered naturalism that manifests through the Madonna. The drapery of her clothes follow the shape of her body, there is a gradation of light and dark that suggests her figure and her body is stocky and proportionate.

The representation of the Madonna (or Mary) started to look more like a real person and less like a mere drawing. This trend of mimesis peaked at the high Renaissance; the more life-like and naturalistic the art appears the better the art was. Many people (both then and later) equated this development as an improvement in the quality of art and prized mimesis as a basis for deciding which pieces of art are better.

This emphasis on mimesis can still be seen today in situations when one is asked to paint a picture. When the picture is painted, we expect it to look like the subject and the more photographic the quality or the more illusory devices are used, the better it is considered. When the work deviates from being mimetic, it is deemed childish or lacking in “proper” technique.

Aside from the elevation of naturalism, another legacy of the Renaissance is the bias towards intellectualized compositions. A lot of the Renaissance paintings and artists the average person knows is usually from the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo Da Vinci (Florentine), Michelangelo Buonnaroti (Florentine), Raphael Sanzio (Roman), and Titian (Venetian), to name a few.

Many of these artists do preliminary sketches and studies on their subjects (i.e. the anatomy of their subject’s physique) before they start the actual painting. They are also well acquainted with the use of perspective, chiaroscuro (Italian artistic term used to describe the dramatic effect of contrasting areas of light and dark in an artwork, particularly paintings), and many other techniques that enrich the illusory quality of a painting.

Many Venetian artists use references and characters from Greek and Roman mythology in their works. There is an unspoken rule that the use of classical subjects elevates the status of a painting. The preliminary knowledge of the classics is treated as a sign of class.

Although it wasn’t discussed in our Renaissance class, I also learned that the Renaissance helped launch the Reformation and to an extent, the Counter-Reformation. Art was a display of wealth and status by the rich. Wealthy patrons had commissions done in their name to show their influence.

One of the major patrons was the Church (think Sistine Chapel and religious subjects for many of the paintings during the era) but due to the lack of funding for their projects and commissions, this necessitated the sale of indulgences, which was the last straw for Martin Luther. He nailed his 95 theses at the door of a church and the rest is history.

Going back to the summer before the semester, our professor kept emphasizing how controversial Modern Art was and it was only at the end of the semester that I got the reason why. The later movements in art questioned the necessity for illusory quality in art (and some movements, like abstraction, questioned the need for form altogether), which was one of the prime characteristics of the Renaissance.

People found it difficult to accept splotchy brush strokes and dribbled paint as art because the Renaissance had set the standard for years to come. It was a major movement whose ideals can be still strongly felt today.

In the end, the Renaissance still isn’t exciting to me. Rather it is awesome, inspiring, grand, calm, majestic among many other things. Although I may have had some doubts about taking the class, I don’t regret spending a semester studying it in-depth at all. It was a movement based on Greek and Roman ideals, but at the same time it was a product of its time.

It was great in almost every sense of the word; it was arguably the first of its kind, its main characteristics became pillars of art in the Western world (at least before the modernists came into play) and the later movements were either developments or reactions on it.

I now fully understand why my former teachers couldn’t pass on its greatness in just the span of a few lessons; it was a topic that needed so much more time and patience for one to fully grasp. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 20 (March 15-April 4, 2016): 12.