A relative-finding quest can trigger chain reactions which sometimes go on and on. Our family had a reunion with long-lost China relatives in 2010. The reunion’s itinerary included meeting family friends with the same Chinese surname Chan (曾 Zeng). That meeting sparked yet another successful search for a friend’s family.

While scouring letters and photographs for that search, we unexpectedly reunited half-siblings surnamed Ong (王 Wang). The eldest sister lives in China and she has siblings in the Philippines. Without the mistake I made, they would not have known of each other’s existence.

One of the siblings here is Julian Ong Jr. (王再福 Ong Tsai Hok [Wang Zai Fu]), or Mano Julian, a recently retired municipal treasurer of Lavezares town in Northern Samar. I first became acquainted with his half-sister Wang Lian Zhi (王蓮治) in China a few years back. On Feb. 17, 2013, I visited Lavezares to look for her half-brothers and sisters. On the day I found Mano Julian, his wife Merlita Chua-Ong (蔡玉燕 Chua Diok Yan, Cai Yu Yan), or Mana Melly, was just as ecstatic as he was.

Mana Melly briefly mentioned in our lengthy discussions that she is also Tsinoy and used to live in San Juan, Metro Manila. Her maiden name was Chua. A few months later, I returned to Samar to show Mano Julian photographs of me meeting his sister in China when I visited Quanzhou in Fujian province.

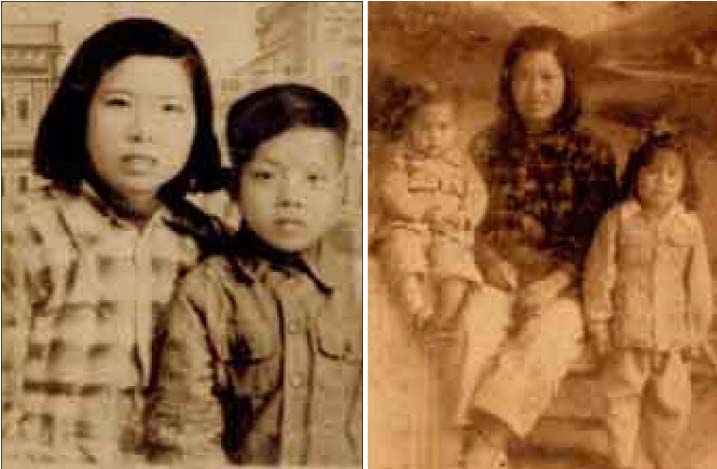

Before I left, his wife handed me a cellophane bag with eight old photos inside. They were in black and white that already turned deep sepia with age. I looked at them: they were all from China. She said her father was a Chinese migrant, Chua Dee Tian. She too has a half-sibling in China. She did not know how her father’s Chinese name is written. She did not say it but I knew she wanted to ask my help to look for her sibling. And thus began this eventful search.

Deductions

To start a good search, relatives’ names and an address are needed. Photos give good clues, but old letter envelopes are best.

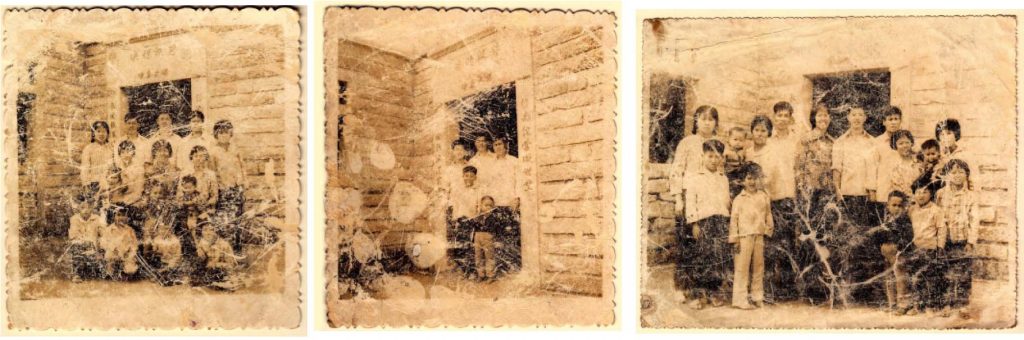

Mana Melly could not identify anyone in the photos, but believed they were her Chinese kin. The old photos were all that remains as mementos of their Chinese roots. I asked her what Chinese dialect her family used. She gave some words in Hokkien which enabled me to isolate her ancestry to the Minnan triangle. This is a region in Fujian which is bordered by Minnan-speaking administrative cities of Zhangzhou, Xiamen and especially Quanzhou.

Some of the old photos seem to confirm this. There was a house in the background, its walls appeared to be of granite stones blocks, a common construction material in Quanzhou.

Unfortunately, Mana Melly did not have a clear photo of her father, just one blurred picture of him taken during her wedding. She lamented he was buried in a public cemetery in San Juan, not in a Chinese cemetery. Chinese inscriptions on a tombstone, which usually names the ancestral village, points clearly to the person’s origins. But we could not find his tomb. The San Juan government does not keep detailed records of those buried in its public cemetery, nor the specific location of the graves.

But even if we had found the grave, it might not have offered much help in our quest: I was told there were no Chinese characters on his tombstone.

Glimmer of hope

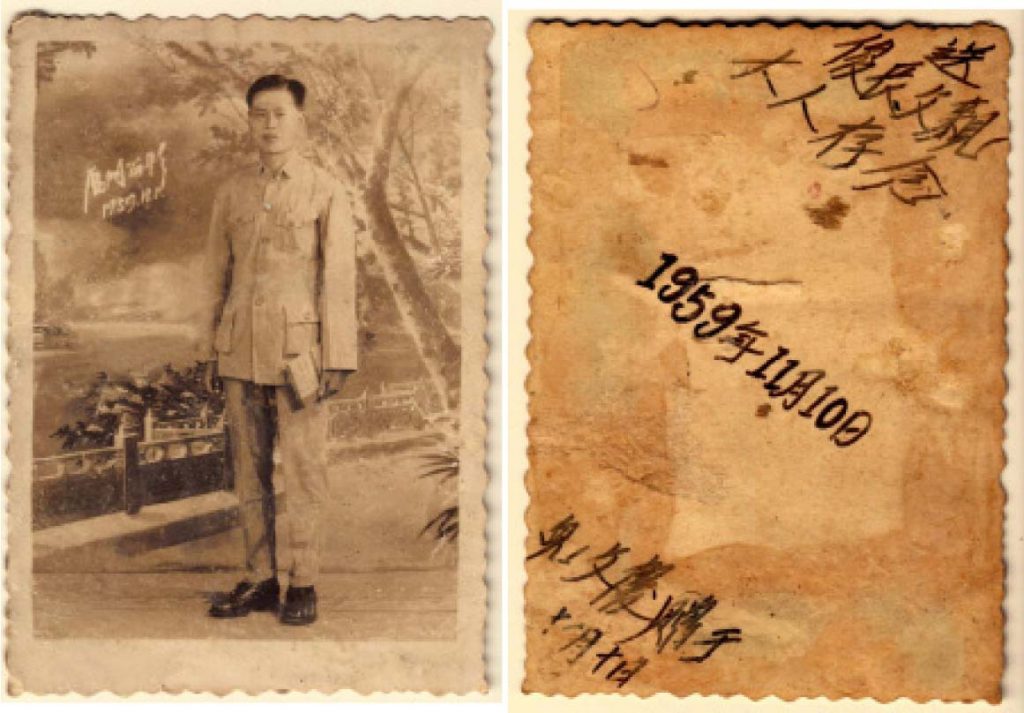

A few months into the search, Mana Melly said another photo had been found: that of her half-brother as a schoolboy. There was Chinese written on the back. Now we have a name, one of the two critical elements needed for a successful search!

The next step was to find a more specific address for him. This brother was said to have settled in Hong Kong. Envelopes of old letters from China would have had address to guide us, but none remained in Mana Melly’s family. On the photo were very small Chinese characters sewn to the breast pocket of the boy’s shirt. Initially, I thought it was a factory uniform. If we could determine the company we could ask for employee records.

Several years after her father died, Mana Melly and her siblings moved out of their home near the San Juan public market. Most of them settled in Samar. One time, while visiting their former home, a neighbor said a Chinese man had come looking for them, especially for her father. It was her Chinese half-brother. Unfortunately, the neighbors did not have their new addresses in Samar, nor did they get the man’s contact information.

Social media

To help in the search, I created my own Facebook group, Relative Finder: How to Search Your Roots in China. I wanted an easy and widely accessible venue for the exchange information between people who want to search for their roots in China; want to meet their relatives in China; have found their roots in China and want to share their stories and experiences; want to help find other people’s roots in China.

I added the scanned copies of the old pictures and this particular quest became one of the first active – and eventually successful – searches made through the group. In particular, my first call for help was the interpretation of the schoolboy’s photo.

New partner in crime

Through this community, I added friends and relatives who were involved in previous or ongoing searches. Edward Richard Ty Lim (林以驊 Lin Yi Hua) is one such fellow. He and his parents are avid readers of Tulay. Upon reading my articles, he looked me up on Facebook to ask if I could help do a similar search for him.

Ed is very keen on studying Chinese language, culture and ancient history. With guidance from his dad, he can work with both traditional and simplified Chinese characters. He helped me translate the Chinese messages on the back of the old pictures and also did online searches for websites that were encoded almost entirely in Chinese. This was one of our first collaborations and his help was invaluable!

Ed browsed through the album I posted in the Relative Finder online community. In three of the old photos were inscriptions on door posts – couplets – a traditional and notable feature in Chinese architecture. But the poor state of the photos prevented us from reading all the Chinese characters.

Then, we tried to decipher the meaning of the messages on the reverse sides. One of the notes that looked important says, “俊長父親 (Given to father Jun Chang or Chun Tiong in Hokkien).” Thus, we discovered Mana Melly’s father’s true Chinese name: Jun Chang may have used Chua Dee Tian in the Philippines.

The family name Chua (蔡 Cai), Ed said, would help narrow the search. The message on the schoolboy’s photo gave the brother’s name: Chua Bon Kheng (蔡文慶 Cai Wen Qing). We deduced that the photo was sent by Cai Wen Qing to Mana Melly’s father to show he was dedicated to his studies.

Indeed, another photo from the original eight showed a boy who looked like Cai Wen Qing. He wore a school uniform and was even holding a book. That one has an inscription noting the city of Xiamen. Was that the location of the studio or the school? We could not tell.

Breast pocket patch

Looking again at the last solo portrait of Cai Wen Qing, I asked Ed about the patch on his shirt. The first two characters looked like 晉江 (Jinjiang City). Ed said the entire patch might read 晉江第三中學 (Jinjiang Third High School). He was not sure of the third character because it was so blurred it almost look like a black square.

But the fourth character 三 was the number three. So, combining the third and fourth characters probably was 第三, or “third.” Ed was now pretty sure the patch gave that exact school name.

Ed found webpages referring to 晉江第三中學 (Jinjiang Third High School). The writing was all in simplified Chinese. On one of these sites, someone had given the school’s history. Mentioned was the school’s original name 晉江市金井毓英中 (Jinjiang City, Jinjing Town, Yuying High School). It was changed only to Jinjiang Third High School in 1952.

The old name, Yuying High School, was more well-known. Yuying High School can easily be found on many Chinese webpages, including one that mentioned a Philippine branch of their alumni association. Another listed its telephone number and exact address. We figured since families tend to want their children to go to school near home, Cai Wen Qing’s village may just be nearby.

First attempt

With the school’s contact information in hand, I wrote a letter to the school principal via the fastest route available: email. Perhaps someone there will recognize the school uniform. I wrote on Oct. 30, 2013 asking if records still existed of students who were there in the 1950s. If yes, do the records include that of Cai Wen Qing? Would the student’s address be listed?

Lacking Ed’s proficiency in Chinese, I wrote my original note in English and used Google translate for the Chinese version. I did not receive any response. Perhaps my letter was poorly translated. So, I printed the email and sent it by courier so that there is online tracking if the letter did indeed reach the school.

I put down my Chinese nephew Shen Yang Qian’s (沉洋謙) phone number – with his permission – in case the letter got lost. He knew of my quests and how I helped his family reunite with their kin in Samar. So he too volunteered to help me follow up my inquiry by calling the school itself. The school said it is the one indicated on the breast pocket logo. But alas, most of the school records from the 1950s were lost.

I followed up on the other lead: that Cai Wen Qing might be living in Hong Kong today.

In April 2014, my family and my wife Sierra’s family visited Hong Kong and Macau. I printed Chinese flyers with help from my nephew Shen Yang Qian who composed the message. I dropped or pasted copies of these in almost every public area we visited: trains, escalators, public buses, ferryboats, ships.

I posted these in Hong Kong Disneyland rides and in the most-visited historic buildings in Macau’s World Heritage Site, inside restaurants, boutique shops, walkways, police stations and even inside restrooms and atop urinals. In all, I posted 50 flyers, most of them on the busiest train stations that zigzag the metropolis. The message on the flyer, an appeal for help in our relative finding quest, was also an appeal for greater understanding between the Philippines and Hong Kong whose relationship at that time had gone sour.

My heart jumped each time I saw someone pick up and read my flyer. Not just because it is one chance that someone who may have known Cai Wen Qing; it is also one more person who now may recognize that the link among the Philippines, Hong Kong and China includes familial bonds and that it goes deeper, beyond current disputes between our countries.

Returning home, I hoped someone may have recognized Cai Wen Qing. I hoped for success…but nothing happened.

Third attempt

Funny how providence brought me new clues! I read every issue of Tulay. In the community news page of the May 6-19, 2014 edition, I saw a photograph of the April 27 opening ceremonies of the “China-Philippines Paintings and Calligraphy Exhibit” sponsored by The Overseas Chinese Alumni Association of the Philippines (旅菲各校友會聯合會 or simply 校友聯 Hao Yu Lian).

I recalled that the website of Jinjiang Third High School had a Philippine branch of its alumni association. Cai Wen Qing’s school photograph was dated 1957. I decided to ask the school’s local alumni association for help. Perhaps someone from batches 1957, 1958 and 1959 would recognize him when they see the picture.

I found the parent alumni association office. The secretary there confirmed that the school’s alumni association is a member of their umbrella organization. Finally, I asked if I could be in touch with alumni members for Jinjiang Third High School.

She also recalled that the previous president of the association, Eddy Ong Guzman (王榮旋 Ong Eng Suan or Wang Rong Xuan) of the Chinese Amity Club (菲華聯誼總會) was an alumnus of the school. What’s more, Ong Eng Suan’s son is a trustee of Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran which publishes Tulay. She said perhaps the son can help us liaise with other branches of their school’s alumni association in the mainland or Hong Kong. She gave me the son’s number since she said she coordinates with Ong through his son.

I went straight to Bahay Tsinoy Museum in Intramuros where I learned Ong Eng Suan is the father of Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran board member Michael Chen Guzman (王培元 Wang Pei Yuan) and Kaisa’s current executive vice president. I got in touch with Michael, showed him the old photos which he passed on to his dad. Within hours, they had a lead!

The next day, Michael asked for Mana Melly’s number. They had found her half-brother Cai Wen Qing, and is still alive!

Apparently, during a fundraiser for Jinjiang Third High, Cai Wen Qing had made a donation. Consequently, his name and contact information was recorded in the list of alumni donors. Indeed, he and his family now live in Hong Kong but he sometimes returns to the mainland to visit the Chua ancestral village.

According to Michael, the Cai hometown is Eh Pian (下丙), near Jinjing town (金井 and 30 minutes away from Jinjiang. Yuying High School is very near their hometown. I was told the son Cai Wei Wang (蔡徫望) would be our main contact for now. Cai Wen Qing is often in the mainland. I made contact through Wechat, an online mobile phone messaging software in Hong Kong and China.

My friend Ed helped me translate Wechat messages from Cai Wei Wang. He introduced his family: Cai Jun Chang had three sons and one daughter. The eldest is the daughter, Cai Wen Qing is the second, the third died in Taiwan in 2005, and the fourth is in the mainland.

Cai Wei Wang also mentioned he recognized the people in the old photos. They were relatives. Cai Wei Wang sent me eight recent photographs of their family. Cai Wen Qing’s resemblance of the old photos to the new photos is uncanny! I reciprocated by sending recent photos of Mana Melly’s family.

I forwarded the China photos to Mana Melly by courier. The two half-siblings have yet to meet, but family photos have already been shared. Given the lack of reliable Internet service in Lavezares, I continue to be the conduit for communication between the two families.

This search has been through so many hurdles and challenges. But the realizations and knowledge gained and friendships built make it more a priceless gain rather than wasted time.

For one, the experience is a testament to the power of photos as tools of searching lost kin. It is another quest accomplished. It is also a discovery of other different routes to help find relatives. Social networks were used heavily, both online and off. The extended network included conversations with Kaisa, Tulay and the Filipino Chinese Alumni Associations!

This is also the first successful find coursed through the online group I created. Modern technology, like Facebook, Google, Wechat has proven to be very powerful collaborative tools in searching for roots in China, even though Facebook has been banned in the mainland.

Technology, old-fashioned visits and relationships together help build bridges that enable families to come together. — First published in Tulay Fortnightly, Chinese-Filipino Digest 28, no. 20 (March 15-April 4, 2016): 8-11.