Some 90 percent of Tsinoys are Christians belonging to Catholic, Protestant, or native Philippine churches. Only about five percent believe in Buddhism only or any form of Chinese folk religion.

Yet, tradition dies hard. Centuries of living in the Philippines have embedded Chinese customs, beliefs and practices into the tapestry of local life, including religion. What follows is a colorful, unique woven pattern of Tsinoys practicing overlapping beliefs, traditions and practices from Christian and Chinese religious traditions.

One example is the veneration of the Catholic Virgin Mary and the Chinese goddess – Ma Cho in Hokkien, Mazu (媽祖) in Mandarin – one of the most revered among Chinese deities.

Ma Cho is the protector of seafarers. Since the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Chinese seafarers have brought a Ma Cho image along whenever they set sail.

She is revered by the early Chinese, especially by Fujianese, who sailed to Nanyang (南洋 south seas) to find their fortune. Her mortal life began in Fujian province. As a deity, she is popular in Taiwan because most Taiwanese are from Fujian. Yet, strangely, this is not so in the Philippines, where 90 percent of the ethnic Chinese are from Fujian.

It may be due to religious syncretism when Chinese and Catholic rituals and practices have blended together. There is a conflation – merging into one – of Ma Cho and Mary. It is popularly known as “Mama Ma Cho and Mama Mary” in Taal, Batangas and in San Fernando, La Union.

This phenomenon is unique because it is a tradition practiced by both Filipinos and Tsinoys in simultaneous Christian and Chinese rituals. Even more interesting is that this conflation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven with the Ma Cho Queen of Heaven happened very early during Spanish rule in the Philippines.

Lady of Caysasay

The earliest account of the existence of Ma Cho veneration in the Philippines can be traced back to 1603, the beginning of Spanish occupation.

Taal town is home to the image the Ma Cho.

The old folks believe it was brought by the Spaniards and thrown into the ocean to pacify the ravaging sea tempest. The waves pushed it into the Pansipit River in Batangas.

Or it could have been dropped accidentally when the Spaniards were exploring the river, which links Taal Lake to Balayan Bay.

But the more popular tale said fisherman Juan Maningcad, while fishing, found a wooden statue caught in his fishnet and kept it in a nearby cave.

In the dark cave, he saw that the waterlogged statue, about six inches tall, glowed. So he brought it home.

Since then, there have been stories of miraculous happenings, including a report that while the catch was poor for other fishermen, Maningcad’s was bountiful.

The stories reached the parish priest, who went to Maningcad’s house and reportedly saw the statue’s face “twinkling like a star.” He declared it was the image of the Virgin Mary and brought it to the capital. Sister Maria Espiritu, appointed to look after it, took it home. To keep it safe, she had an expensive urn specially made for it.

However, when some Fujian Chinese saw the image, they claimed it was that of the goddess Ma Cho.

For the Chinese, Ma Cho is the protector of voyagers – not much different from the Catholic Virgen del Buen Viaje (Virgin of Good Voyage) in Antipolo.

Now you see it…

The caretaker, Sister Espiritu, reported that the image disappeared every night, and was back again in the morning. Frightened and worried, she told the priest. The priest and some devotees kept watch one night. They saw the urn open and a bright light surrounding the apparition of Virgin Mary appeared. They followed it to Caysasay and surmised that the vision wanted its sanctuary to be on the site where it was found.

The priest decided to display the image in the main Taal church. But the figure continued to vanish and reappear the next morning. One day it disappeared completely and could not be found. After some time (reportedly in 1611), two young women, Maria Bagohin and Maria Talain, gathering firewood saw the figure hovering on a branch of a sampaga tree where kasaykasay (kingfisher) birds reposed. Hence, the name Lady of Caysaysay came about. The women ran back to the town and told the priest what they saw.

The Taal people believed the figure really wanted to be there. Hence a chapel was built on the banks of the Pansipit River, in Barangay Labac in Taal, in 1639.

In Taal itself, about 20 or so years ago, controversy arose over where the statue should be housed. Bishop Rufino J. Santos ordered it moved to the imposing St. Martin’s Basilica on top of the hill, just a stone’s throw away.

Stories are now told that each time the image is brought to the big church, it would return to the small Lady of Caysasay Shrine in Labac. A compromise was consequently made: the image was to be in Labac Thursday morning to Saturday afternoon and in the Basilica the rest of the week.

A papal order later ensured that the practice continued until recent years.

In 2003, the 400th anniversary of its discovery, the image of Our Lady of Caysasay was declared a National Historical Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines. This ended the practice of splitting the image’s time between two churches. Instead, a procession every last Saturday of the month brings the image to the Basilica, where it stays until the last high mass, and then is returned to the shrine.

Chinese connection

Batangueños report that many Chinese contributed to the building of Labac’s Our Lady of Caysasay Shrine. The priest and parishioners are grateful to the Chinese who contributed substantially to the shrine’s renovation and upkeep.

The timeline of the Caysasay figurine’s existence among Filipinos is marked by tragedy among the Chinese. The year it was fished out, 1603, saw the first big massacre of the Chinese. Could it have accidentally fallen off the boat of Chinese trying to flee?

Another significant coincidence happened in 1639, the year the Labac shrine was built. That year saw the second biggest Chinese massacre. The Chinese uprising began in Calamba, Laguna, and spread to nearby provinces like Batangas and Rizal. The ensuing bloodshed claimed the lives of 30,000 Chinese. The Filipinos, especially those in Taal, sided with the Spaniards and went on a killing frenzy.

It is an oft-repeated story of elderly Chinese that Taal is the only town in the whole country reportedly with neither Chinese residents nor Chinese-owned sari-sari stores. As of July, residents say there are still no Chinese-owned stores, although there are mestizo-owned ones. Taal native Pio Goco speculated that Chinese shopkeepers stayed away because Batangueños are fierce competitors, and among the most business-minded people.

Whether the Chinese absence is in truth due to the two massacres is mere speculation.

In 1639, the miracle attributed to the shrine’s completion was connected to Hay Bing, a Chinese who was to be beheaded by the Spaniards but was saved by the Ma Cho because of his devotion to her, manifested in Our Lady of Caysasay. The popular story was that he survived the beheading but more feasible was he was hidden by the miracle of the Virgin’s protection.

Over time, veneration of Mama Mary and Mama Ma Cho as one helped the people of Taal and the Chinese there rise above the early animosity that arose from past tragedies of the massacres. The common faith and belief brought about an encompassing degree of assimilation.

Ma Cho veneration

Since the early 17th century, the Chinese, especially in Batangas, started revering and worshipping the Ma Cho in traditional Chinese rituals.

In 1954, during the Marian Congress in the Philippines, Pope Pius XII designated Ma Cho as one of the seven manifestations of the Virgin Mary – Our Lady of Guadalupe, Lady of Manaog, Lady of Peñafrancia, Lady of Peace and Good Voyage, Lady of the Holy Rosary of Piat, Lady of Namacpacan, and Lady of Fatima. This helped intensify the Ma Cho belief, especially since word of mouth attested that all wishes requested of her were granted (有求必應 ).

After World War II, Chinese in neighboring towns of Batangas such as Lipa, Tanauan and Rosario, and nearby Lucena and Candelaria, Quezon where the Chinese community is relatively large, started a more formal worship of Ma Cho.

Celebration, divination

Reportedly, beginning 1961, from November 28 to 30 each year, the towns take turns putting up a makeshift stage-cum-altar in their respective towns to celebrate the eve of the birth anniversary of Our Lady of Caysasay, which they venerate as the goddess Ma Cho.

The sponsoring town would borrow the image from Taal, place it at the center of the stage and lavishly celebrate the festival with firecrackers, Chinese opera performances, devotions and food offerings, burn incense and paper money, ask for divination and end with sumptuous banquets.

Starting early morning of November 28, thousands of devotees would arrive from nearby Batangas towns, Manila and neighboring provinces like Cavite and Quezon. They bring offerings of incense, paper money, flowers, fruits and food, filling the table in front of the altar.

Entertainment is slated during the three evenings of celebration. Chinese opera troupes hired from Manila perform nightly opposite the altar, capping the daylong festivities.

After their offerings and devotions, devotees ask for divination. With the use of half-moon divination tablets, which the local Chinese call pua-pue (博杯), they would seek advice regarding business, family, marriage or implore for help in curing illnesses or solving problems.

The Ma Cho cult became widespread because of stories, spread through word of mouth, about miracles and answered supplications, including saving people from tragedy.

Since then, people from all over the country, from as far as Mindanao, come to burn incense and offer devotions.

The annual Chinese-style rites, worship and celebration is made more fascinating by a special mass by a Catholic priest, in English or Tagalog, in front of the temple on the last night of the three-day festival. Afterward, the image is paraded down the major streets in an elaborate two-hour Catholic procession. When the image returns to the temple, there are firecrackers and a lion dance.

Putting up the makeshift altar for the annual festival consumed a lot of resources. So the Chinese in Batangas City, which has the largest Chinese community in that province, spearheaded a move to build a traditional Chinese temple to house the replica of the Lady of Caysasay.

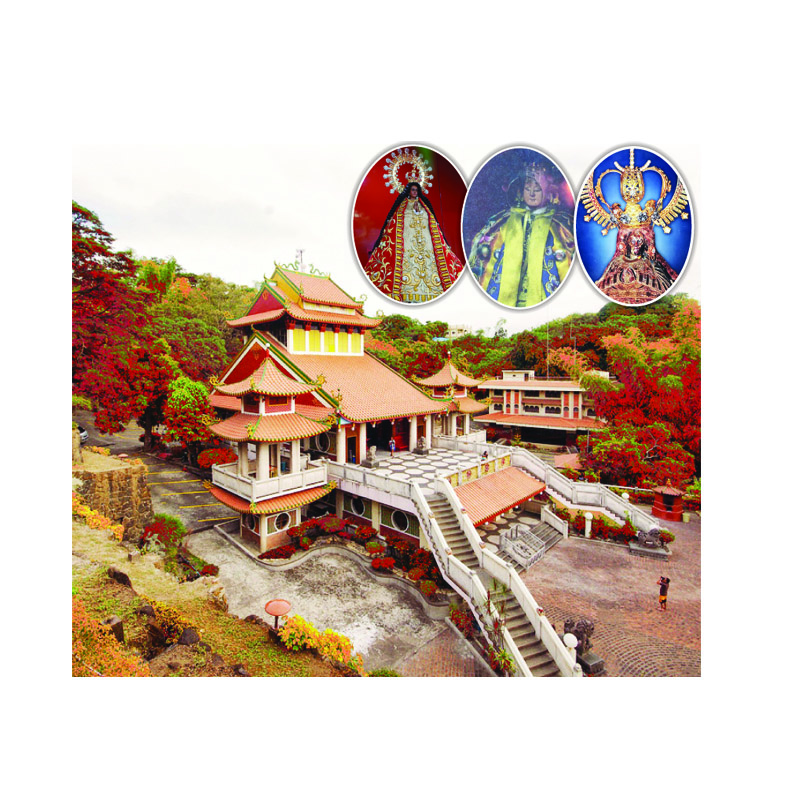

Ma Cho temple, Batangas

In 1975, a Ma Cho temple was built in the campus of the Chinese school, Kip Si, in Batangas City. The temple was built entirely in traditional Chinese style, complete with dragons, arches and carved stone pillars.

A big sign above the entry reads “Mazu Hou Kong (媽祖后宮)” or Temple for the Goddess Ma Cho. Yet the image on the altar is garbed in traditional Catholic raiment for religious images, bearing no resemblance to the traditional image of the goddess Ma Cho.

Chairman of the temple’s board of trustees, William Alcantara (黃普澤), reported that since 1975, busloads of devotees flock to the temple each year to celebrate Ma Cho’s birth anniversary (23rd of the third month, lunar calendar) and Mama Mary’s feast day on December 8 (Gregorian calendar).

This highlights the conflation of Ma Cho and Mary that both feast days are big celebrations.

Chinese devotees return year after year with offerings in cash and in kind for the Chinese temple and the chapel in Labac, where the original image of the Virgin of Caysasay still resides. The temple shares the offerings with the nearby orphanage, old folks’ home, and school to fulfill the spirit of Ma Cho.

Aside from the main replica of Our Lady of Caysasay, three smaller figurines (ku 龜) are displayed on the altar, to be brought home by the lucky persons assigned or chosen through the divination tablets.

Hosting ku at home supposedly brings good fortune to the homeowner for the whole year. The ku hosts would bring back the replicas on the next celebration and the competition to bring it home is repeated.

The Catholic priest who presided over the mass during the Ma Cho festival in November 1998 admitted he was uncomfortable on the fusion of Catholic and Chinese rites and the worship of the Virgin Caysasay as the Chinese goddess Ma Cho. But, he said, he could hardly refuse celebrating mass because of the great devotion showed by the Chinese.

Another priest told this author: “Even Mama Mary has many manifestations here in the Philippines. She is the Virgen del Buen Viaje, the Nuestra Señora del Pronto Socorro, the Immaculate Concepcion, La Consolacion and so on. So, why can’t she be Ma Cho, Queen of Heavens?”

Ma Cho, San Fernando

Trustees of the La Union Temple hold that their Ma Cho recognizes the Mazu in Meizhou, Fujian province as her ancestral origin but relates her own origin to Our Lady of Caysasay, hence her annual visit to Taal, Batangas.

Since the 1960s, Chinese Ma Cho devotees in San Fernando, La Union travel to Batangas for the annual veneration of Our Lady of Caysasay/Ma Cho.

They also go to Taiwan to participate in the Tai Ka Ma Cho (大甲媽祖) celebration there.

They continue the annual pilgrimage to Batangas even after their own grand Ma Cho Temple was built on two hectares of land in 1978. Founders were the Chinese elders in the community, says Aldrico Dy, president of the Ma Cho Temple Foundation in San Fernando.

Every year, thousands of devotees in the city flock there on the sixth day of the eighth month in the lunar calendar, which coincides with early September in the Gregorian calendar.

It was a series of events that led to San Fernando receiving its own Ma Cho image, and eventually a temple.

The image was a gift from a big Taiwanese fishing vessel that was detained there. The Tsinoy community helped the Taiwanese negotiate with the government for their release. In gratitude, a big image of the Ma Cho was given to the mayor and a smaller one to the Tsinoy community.

The figure was placed in the brotherhood association (ho cho shia 互助社), a group organized by early Fujianese businessmen who are sworn brothers (結拜兄弟). They celebrate the Ma Cho feast day with grand festivities with donations from the Tsinoy townsfolk.

Dy also said San Fernando, La Union was hit by a series of big fires: in 1949, 1959, and the biggest, in 1969, saw the entire central business district, including the market, razed to the ground. After the fire, residents had asked Ma Cho for protection.

The spirit of Ma Cho urged the residents to build a temple and through divination identified the site: on a hilltop facing the vast blue sea (坐山面海) that leads to the South China Sea.

In the past, Our Lady of Caysasay/Ma Cho was invited to San Fernando during feast days. Three days of feasting featured Chinese opera performances, lion dances, food offerings and fireworks.

The celebration ends with a Catholic high mass.

When the Ma Cho statue became a cultural heritage figure in 2003, the process was reversed: La Union’s Ma Cho is brought to the Caysasay Shrine in Batangas. Devotees filled three buses and headed south, to be greeted on arrival with a welcome banner: “Welcome, Mama Ma Cho, Mama Mary, one and the same.”

Our Lady of Caysasay and its La Union counterpart are joined in a procession to the basilica. The priest celebrates high mass in the evening, and a fireworks display ends the program. An all-night vigil of devotees is held until 2 a.m. the next day, when the image and the La Union devotees return home.

Filipinos join in welcoming the La Union Ma Cho every year. Devotees from out of town also flock to the basilica and Labac’s small shrine for the celebration.

Batangas Ma Cho, Lady of Caysasay, La Union Ma Cho

Ma Cho pilgrimages from La Union to Batangas for the annual celebration stopped after a police raid on mahjong games held during the Batangas festivities. The celebration was eventually resumed.

In the late 1990s, then Archbishop of Lipa Gaudencio Rosales – who later became Cardinal – exhorted Taal’s lay leaders to revive the congenial relationship with the Chinese community.

He emphasized that devotees believe Our Lady of Caysasay, Mama Mary and Mama Ma Cho are one and the same. The relationship between the two images was eventually formalized.

His successor Archbishop Ramon Arguelles continued to encourage harmonious relationship of the Chinese community with the Taaleños.

After its inauguration in 1978, the San Fernando Ma Cho Temple launched its annual pilgrimage to Taal for devotees. The Batangas devotees likewise have their pilgrimages to San Fernando. The Blessed Virgin of Caysasay Foundation Inc.’s efforts have improved collaboration between San Fernando and Taal, with more local participants in the pilgrimages to Taal, a major event much anticipated by both the shrine and the basilica.

The original image of Our Lady of Caysasay, upon the invitation of the Ma Cho Church, Inc., had visited the San Fernando temple twice in past years. Catholic masses were held at the temple during those visits.

Like the Ma Cho temple in Batangas, the San Fernando temple also has smaller replicas. Devotees also use divination tablets to determine who brings home each of the four replicas.

In 2003, the San Fernando temple participated in the celebration of the 400th year of the discovery of the Caysasay image. It sent a delegation, and sponsored a fireworks display to mark the celebration’s finale.

In recent years, the temple made a substantial donation to the basilica to pay for repairs of serious damage caused by an earthquake.

The relationship among the shrines in Taal’s Lady of Caysasay, Batangas’ Ma Cho goddess and San Fernando’s Ma Cho Temple is unique in the world.

Acceptance of a deity as both Catholic and Chinese by both Filipinos and Tsinoys is an excellent example of how faith and religion can unify and bind people together.