In journalism parlance, “writing 30” means the end of a story. Not so with Tulay. The fortnightly Chinese-Filipino news digest is celebrating its 30th year of publication with this June issue.

In journalism parlance, “writing 30” means the end of a story. Not so with Tulay. The fortnightly Chinese-Filipino news digest is celebrating its 30th year of publication with this June issue.

Unveiled on June 12, 1988, what was once a monthly news digest that sought to publish stories told from the viewpoint of the Tsinoy experience in the Philippines, Tulay became the lone voice that sounded the alarm and recorded the spate of kidnappings that bedeviled the Chinese-Filipino community in the 1990s.

Known for its coverage of the horrors of kidnappings, Tulay was a rich source of information for the major media outlets since the traumatized Tsinoy victims and their families were only willing to talk to Tulay editors.

This advocacy against kidnapping in particular and criminality in general was recognized early on by the Catholic Church when it awarded Tulay the Catholic Mass Media Award for Best in In-depth Reporting and Best in Advocacy in 1993. In 2001 and 2003, Tulay won the CMMA for Best Short Story and was finalist in the 2003 CMMA Best Feature category.

The editorial staff in the past was composed mainly of non-professional writers and production assistants who not only wrote feature articles in English, Filipino and Chinese but also trained on the job in layouting, editing and proofreading for the news digest. Most of the staffers were doing this on a part-time basis since majority held full-time jobs elsewhere.

Copies were delivered by runners, edited manually and laid out in the cut-and-paste mode in the first few years. There was no spell-check then, no email that we can send attachments to.

Were there boo-boos committed? You bet. Some stories were chopped for lack of space, errors in grammar and syntax were made, editorial decisions were sometimes heatedly debated upon, egos were bruised, tempers flared. But one thing remained constant: Tulay’s will to serve as a bridge did not diminish one bit.

Aside from the spate of kidnap stories, Tulay also sought to enlighten and educate its readers. Though it appeared as an insert in the Chinese news daily World News, it also had its own subscribers.

True to its slogan of being a bridge of understanding between two cultures and a bridge of tolerance between two ages, the people behind Tulay understood that to reach a wider and younger audience, it had to use English as its main language since the use of Chinese was eroding, especially for the younger generation. To encourage the young, it included a student page that welcomed contributions by Tsinoy youth.

It is probably the only publication in the world that has a Filipino masthead (Tulay, meaning bridge) and that churns out articles in three languages (English, Filipino and Chinese) about the local Chinese-Filipino community and issues of national import that affect it.

It sought to demystify certain misconceptions and stereotypes about Tsinoys. Tulay featured stories about Chinese Filipinos who are standouts not only in the field of business but also in the “unChinese” arena of music, arts, various professions, education and nongovernment organizations, among others, that may have been overlooked by the national media.

Stories extolling the everyday heroism of folks like the volunteer fire fighters, the Wha Chi and other guerilla groups were also found in its pages. Conversely, it did not shirk from shining a spotlight on Tsinoy miscreants like Rolito Go and unrepentant Chinese drug lords.

Aware of the challenges facing it as a monthly news digest and unable to compete with the dailies or weeklies, its small team of writers strove to find new angles in presenting its stories.

Tulay is proud that some of its stable of writers in the past and present cut their teeth with the news digest when they were virtual unknowns in journalism and literature.

Among its notables who have gone on to greater publishing heights are Caroline Hau (author and literary writer), James Ong (current editor in chief of Mabuhay, the in flight magazine of Philippine Airlines), Yvette Tan (author and columnist) and its prolific trilingual writer/translator Joaquin Sy (the in-house Pilosopong Tasyo).

The current crop of editors and consultants include Yvonne Chua, twice winner of the prestigious Marshall McLuhan award for investigative journalism, and Doreen Yu, editor of The Starweek magazine. Both giants in the world of Philippine journalism, they ensure Tulay adheres to the basic tenets of good writing.

The advocacy work of its past and longtime editor-in-chief Teresita Ang See saw her take a leading role in speaking out against the unabated rise in criminality, propelling her to national prominence. It speaks volumes about her integrity that Ang See’s name is synonymous to being an anticrime crusader, a mantle that she wished she didn’t have to wear but is courageous enough to don despite death threats volleyed her way by criminal syndicates.

In 1995, a decision was made to publish twice a month to give the publication more currency and exposure. As in the past, there would be days that stories are hard to come by and it is only through the sheer tenacity of its dedicated staff, editors and loyal supporters and subscribers that Tulay continues to exist.

To this day, Tulay resolutely chugs along, mindful of its duty as a recorder of events both big and small happening in the Tsinoy community in particular and how the issues impact the greater Filipino society.

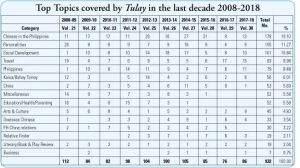

Some of the issues that are tackled in the news digest are timeless in fact. What does it mean to be a Tsinoy? How does it feel to grow up Chinese in the Philippines? How do you retain the uniqueness of the community? Integration vs assimilation and can’t we do both? The pleasure and pain of intermarriage. Stories of women without families to care for them. How do we best contribute to the society that we are a part of? These are some of the topics that remain hot button issues to this day.

At the height of the kidnap-for-ransom crisis, I never thought that I would see the day when members of the Tsinoy community, including my mom and her friends, all very conservative, would actually participate in a rally (Jan. 13, 1993) to call for an end to the unchecked growth of criminality. It was the first and the biggest protest rally led by Tsinoys. Tulay was there to record that watershed moment.

More of these milestone events found their way to Tulay’s pages. Aside from the protest rally during Charlene Sy’s funeral in 1993, another big rally was organized for kidnap victim Betti Chua Sy in 2003, as well as anti-chacha (Charter change) and Tsinoy for Good Governance (anti-corruption) rallies which Tsinoys normally shy away from. During the hostage crisis at Rizal Park in 2010, the Tsinoy community lent full support to the investigating committee on behalf of the victims, all Hong Kong nationals.

More of these milestone events found their way to Tulay’s pages. Aside from the protest rally during Charlene Sy’s funeral in 1993, another big rally was organized for kidnap victim Betti Chua Sy in 2003, as well as anti-chacha (Charter change) and Tsinoy for Good Governance (anti-corruption) rallies which Tsinoys normally shy away from. During the hostage crisis at Rizal Park in 2010, the Tsinoy community lent full support to the investigating committee on behalf of the victims, all Hong Kong nationals.

Tulay was also at the forefront in coverage of the commemoration of significant historical events like the Centennial of Philippine Revolution (1996), the Centennial of Anglo Chinese School (1999), the 70th anniversary of victory in World War II (2015), 75th anniversary of Wha Chi Guerrillas and the 600th anniversary of the visit of the Sultan of Sulu to China (2017).

A lot of things have happened since Tulay started in 1988. For one, it has gone digital, while still keeping the print copy. Its cover and back pages are colored.

Conscious of the new immigrants and their children, Tulay added more pages on China and Chinese culture and a section on Proud to be Pinoy, shining moments for Filipinos in the international arena. To preserve Tsinoy culture, we added Eleonor Tan’s Hokkien Idioms and to link the Tsinoys with their long lost Chinese relatives, we have Eduardo Chan de la Cruz Jr.’s Relative Finder.

Even though Tulay has reached the ripe age of 30, there are still stories in the Tsinoy community to tell, events to record, feats to celebrate and foibles to expose.

Don’t write 30 on Tulay, just yet… and let’s hope not ever.