We celebrate two significant events this year. The 200th birth anniversary of Francisco Mercado Rizal, and the 120th commemoration of our Independence Day (June 12, 1898). Both dates are closely tied with the narrative of our National Hero, Dr. Jose Rizal. He was born June 19, 1861, in Laguna, the first province that led the revolt against Spain. His father was Francisco Mercado and mother, Teodora Alonzo.

Francisco Mercado

Francisco Mercado

Mercado was born in Biñan, Laguna on May 11, 1818. He came from a moderately well-off family, which enabled him toattend a Latin school in his hometown. He later entered the College of San Jose in Manila to study Philosophy and Latin.

He married Teodora Alonzo on June 28, 1848 and moved to Calamba. They had 11 children. Jose was their seventh.

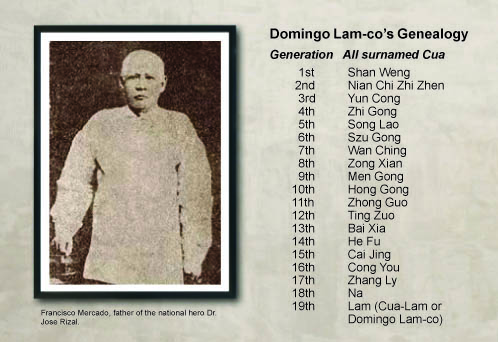

His forebears were Chinese from the village of Siongque in Lamua, Fujian, China (see chart for Mercado’s Chinese ancestors). His great great grandfather was Cua Lam (family name Cua, first name Lam) and was called by his nickname Lamco (suffix “co” meant respected brother). He was christened Domingo Lamco after he was baptized.

Mercado was a tenant of a Dominican estate in Calamba. Through hard work and efficient management of his farms, he increased his landholdings.

Financially comfortable and respected by the townspeople, he became cabeza de barangay of Calamba. He was the first to own a bahay na bato there. His family was cultured and well educated, prominent in social and cultural activities, and his children studied in Manila schools.

Mercado changed the family name to “Rizal” in 1850 after an order from Governor General Narciso Claveria mandated that all native Filipinos should have a distinctive family name.

He died on Jan. 5, 1898 in the Manila home of his daughter Narcisa. He was 79.

Jose Protacio Mercado Rizal

Jose Protacio Mercado Rizal

When Rizal first applied to go abroad, he dropped the middle name Mercado to disassociate himself from his brother Paciano Mercado. Paciano was then under surveillance of Spanish authorities because of links with the martyred Filipino priests Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora.

Rizal also needed a fresh identity so he could travel freely abroad and avoid being hassled by the Spanish inquisition.

Much has been written about Rizal and the inspiration of his two novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. Rizal and many ilustrados were the educated middle class who studied first in universities in Manila, then abroad.

In Europe, these ilustrados absorbed the liberal ideas of the West that opened their eyes to the shackles of Spanish imperialism and oppression. They started a reform movement, hoping to influence Spain to institute reforms for the future of the Filipinos. When the movement failed, this enlightened class led the national revolution.

The Philippine revolution of 1896 is closely intertwined with China’s Xinhai revolution of 1911, a fact which had been discussed earlier in the article “The Xinhai Revolution: End of Imperial China” (Tulay, Oct. 4-17, 2011 issue) Rizal’s life and that of Sun Yat-sen, the father of China’s revolution likewise has many parallels. (See sidebar story).

Calamba, Laguna

Calamba, Laguna is not just Rizal’s birthplace. Its close connection to the early Chinese in the Philippines is a hitherto little-known historical sidelight.

All of Laguna, including parts of Rizal and Batangas provinces, were encompassed in an area called Bay or Ba’I.

The recent study of historian Go Bon Juan proved that the Ma’I in ancient Chinese records refer to Ba’I.

Ma’I is the first place in the Philippines ever mentioned in ancient Chinese records, or in any foreign account for that matter. The place appeared in an edict of the fourth year of Kai Bao (Song Taizu 971 AD) in vol. 186 of the Song Dynasty Annals. Ma’I was also mentioned as “part of a luxurious Chinese foreign trade.” This is solid proof that places in the Philippines, such as Ba’I, had extensive trading networks with China 500 years before the coming of the Spaniards.

Ma’I appeared in 10 other accounts during the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties. The long account on the “Kingdom of Ma’I” appears in the customs inspector Zhao Rugua’s Zhu Fan Zhi (1225), and a second one is in the chapter on “Ma-I” in Wang Da-yuan’s Dao Yi Zhi Lue [Records of the Barbarians of the Isles] (1345). The first narrative lists trade items like yellow wax, cotton, pearls, tortoise-shell, medicinal betel-nuts, and yuta cloth; which foreign traders barter for porcelain, trade-gold, iron censers, lead, coloured glass beads, and iron needles.

Hence Ma’I, which refers to Ba’I, Laguna, is significant in Philippine historiography in general and in studies of Philippine relations with foreign countries in particular.

When the Spaniards first visited the region in 1571, they found large communities of Tagalog residents trading with the Chinese along Laguna de Bay’s shores. After the Spaniards established settlements there, Bay (original spelling of Ba’l) became the center of trade and the first capital of the province. The fertile soils of Laguna provided much needed supplies and resources. The haciendas or lands were managed and controlled by the Spanish friars, which also led to several disputes among locals and Chinese traders.

Calamba was the town where, in 1639, the second massacre of the Chinese occurred. In the first 1603 massacre, the Chinese killed were mostly from Manila.

The 1639 uprising however, started in Calamba and quickly spread to neighboring towns in Rizal and Cavite, and Manila: perhaps a precursor of the revolts of eight provinces led by Laguna in 1896.

The Spaniards conscripted 1,000 Chinese to open up the frontiers of Calamba. Harsh working conditions and poor health and sanitation saw 300 die from malaria infection in the first few months of work. Alcalde Mayor Don Luis Arias de Mora extorted even from the workers: he forced them to give up a part of their harvest as taxes, which drove the workers to desperation. The farmers armed themselves with crude bolos, fire-hardened bamboo poles, makeshift farm implements as weapons and attacked Calamba on Nov. 20, 1639.

At the end of the siege, 25,000 (Spanish sources) to 33,000 (Ming Annals) Chinese were killed. It was one of the darkest periods in the history of the Chinese in the Philippines. Agrarian conflict persisted and the persecution and cruelty of the Spaniards continued up till the end of the 19th century. In 1896, Laguna was the first province to rise up in arms against the Spaniards, signalling the start of the national revolution.